Andrew J. Lovejoy’s knowledge of hog production was earned the old-fashioned way, through trial, error and unflinching dedication

In 2024, the name Andrew J. Lovejoy isn’t widely recognized within North America’s hog industry. But more than a century ago, the farmer from the northern part of Illinois was well-known within hog circles. He had dealings throughout North America and overseas as well as he pursued his passion for pigs.

Advertisement 2

Article content

According to an article in the Rockton-Roscoe News, Lovejoy served as president of the International Livestock Exposition and following his passing in 1919, was inducted into the Saddle and Sirloin Club. He was also president of two different county fairs, was a member of the Illinois State Board of Agriculture for 12 years, and was elected to the Illinois General Assembly.

Raised on a farm along the Rock River, Lovejoy spent many years working as a traveling salesman while running his farm and building a reputation as a breeder of Berkshire pigs. At the age of 69 in 1914, he published ’40 Years’ Experience of a Practical Hog Man,’ a volume that was republished in 2019 with additional chapters attributed to Lovejoy’s contemporaries, including Prof. John M. Evvard.

Advertisement 3

Article content

Lovejoy’s knowledge of hog production was earned the old-fashioned way, through trial, error and unflinching dedication.

“Beginning with a pair of young pigs many years ago, the only way anything concerning the subject has been learned has been by actual experience. This experience has been costly, but what is learned at great expense one never forgets,” Lovejoy wrote for the introduction to his book.

While circumstances no doubt varied widely from farm to farm, for the leaders of the industry in the early 1900s, a growing body of scientific knowledge was being added to the practical knowledge accumulated by hog farmers like Lovejoy.

Agricultural researchers were conducting investigations into various feeding regimens with a goal of ‘balancing the rations’ and introducing such innovations as the ‘free-choice system.’

Advertisement 4

Article content

Market hogs in that era were often marketed at around 225 pounds, similar to today’s standard, though more time was required to reach finishing weight. It takes about four months for hogs to reach market weight today compared to six months or more in the early 1900s. Lovejoy noted that in the early part of the 19th century, hogs were often marketed only when they were 500 to 600 pounds and a few at weights approaching 1,000 pounds.

Corn, barley and other grains were the central component in feed rations but for strong performance other feeds were used, often reflecting the mixed farming systems of that era. Prominent among them were ‘tankage’ or meat meal, byproducts from the meat packing industry. Skim milk, the cream having been sold, was also fed along with other protein sources including fish meal, linseed oil, and soybean meal, the properties of which were just beginning to be understood. Lovejoy even supported the use of food waste, if a sufficient quantity could be sourced.

Advertisement 5

Article content

“Garbage is a splendid swine feed … It takes five to eight pounds of garbage to equal one pound of mixed grain … To feed garbage successfully, it should be fed in large quantities and kept before pigs practically all the time.”

The feeding practice that truly set hog production of the era apart from those of today, however, was the extensive use of pasture and forages as a cost-effective means of balancing the ration. Among the top recommended pasture species were alfalfa, rape, medium red clover and other clovers, and bluegrass at the correct stage of growth.

“The better forage crops, rightly selected, replace these high-priced supplementary concentrates, giving the swine grower an opportunity to produce the equivalent of these high-priced feeds on his own farm, and in such a manner that they will be harvested by the swine, so that much labor will be saved.”

Advertisement 6

Article content

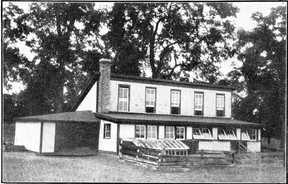

Lovejoy spoke at length about the ideal hog farm, “…it should first have a rich soil, full of fertility to grow grasses and other forage, as well as the grains needed for the best feeds… After a good rich soil, the next thing is a slightly rolling, well-drained farm. If it is underlaid with gravel, as much of our soil in northern Illinois is, it will not require tiling to carry off surplus water.”

Outlined at considerable length in Lovejoy’s book are different styles of hog housing, from portable units for individual sows and their litters to more sophisticated systems such as the Myers Plan Hog House – “…probably the most convenient swine house, with pasture and house attached, that could be built.”

The Myer system features a central feed house surrounded by a circle of roofed pens with such labor-saving, devices as an overhead steel track to transport feed to the pens. Extended outward from the circle of pens, are a series of paddocks for grazing ranging in size from a half-acre to as large as 3.5 acres, the entire footprint being about 40 acres in size.

Advertisement 7

Article content

“To make an extra nice job, the yards could all be fenced with what is known as the galvanized hollow iron post, about two inches in diameter, which should be made five feet in length and driven into the ground and the oven wire fence attached with proper brace, etc.”

Another consideration setting apart from the hog industry of today from what existed a century ago is the use of boars. They are of course essential in either case but in Lovejoy’s time actual boars were kept for breeding purposes rather than relying on AI (artificial insemination).

In choosing boars, Lovejoy turned to conformation, the physical characteristics of the animals along with considerations as temperament. “Generally speaking, the sire should be a little more on the compact order than the sow. By this I do not mean a chunky, short, thick boar, but one showing full development at every point, and of a strictly masculine type. …It should be large without sacrificing quality; smooth and even in every part.”

Advertisement 8

Article content

Likewise, there were traits suggested for sows: “… secure only those that show a good length of body, well-sprung ribs, with deep sides; a full distance; long deep hams, with as straight legs as possible; not too high above the ground when in ordinary condition, with a full heart girth giving plenty of room for vital organs…”

The art of handling boars has, to a considerable extent, become a lost art in modern times. For Lovejoy, the care of boars and other herd members began with kindness.

“The herdsman or owner should never under any consideration misuse the boar, but handle him with a light buggy whip and have him so trained that he can be driven as easily as a horse can be led.”

For larger operators with several boats, group housing is suggested. “They can be so handled as they will run together like a bunch of barrows. This can be done by cutting off the tusks very closely, then on a cool day, turn them all together after thoroughly spraying them with good coal tar disinfectant, and stay with them until they have had their fight out at least once or twice, and the boss has been recognized, after which they will leave each other alone.”

Advertisement 9

Article content

As is the case today, Lovejoy recommended hog producers, whether raising purebreds or swine for the marketplace, keep extensive records on the performance of sows, boars and young animals. “I prefer litters running from seven to nine rather than from 10 to twelve or more… we occasionally find a good sow that can grow a litter of twelve or more, but the pigs are not apt to be as thrifty and as ‘growthly’ as those of a litter of eight or nine.”

Lovejoy employed the use of farrowing boxes at his operation as a means to protect young pigs – “one of the best investments.” After a couple days, he would move the sow and her litters to an individual pen. He suggested special measures be taken when farrowing occurs during cold weather, such as placing a hot rock in a box or barrel, covering it with straw, and then placing new arrivals into this cozy location.

Advertisement 10

Article content

Swine diseases like swine cholera and other ailments were an issue in Lovejoy’s time as they are today but breeders like Lovejoy relied upon the show circuit to promote their herds. Lovejoy did recommend that show animals be isolated from the rest of the herd when they returned home from an extended trip to avoid the spread of disease.

Lovejoy recalls being disappointed but undeterred by his lack of ribbons in his early days showing pigs but was determined to learn from those experiences. His success as a showman reached his pinnacle in 1893.

“… after winning the grand championship at the World’s Fair in Chicago for the best herd, consisting of one boar and four sows, over one year old, my name was finally placed on the map and my son and I have practically discontinued showing since that time.

Advertisement 11

Article content

“I strongly urge the show ring as a means, not only of education for the breeder, but of building up a substantial business.”

Listed by Lovejoy as a leading breeds was the Berkshire – “the aristocrat of the swine breed” – along with Duroc-Jersey, Chester White, Poland China, Spotted Poland China, Hampshire, Tamworth and Yorkshire. In his description of Yorkshires, he noted that, “Canada has progressed much farther than in this country, and is one of the most popular and most numerous breeds found there today.”

Among the other sections of Lovejoy’s book is a chapter focusing on the importance water to success in the hog industry, a consideration no less important today as then but perhaps viewed by Lovejoy in less than a scientific manner and a sense of humor.

Advertisement 12

Article content

“I know personally that I drink and enjoy lots of good cold water, and while it is claimed by some that the drinking of water during the meal is injurious, I have always drunk all the cold water – and it is never too cold – with my meal that I wanted. I am now three score years and still drink water, and have never felt any ill results, and weigh over 250 pounds. I have an attractive stenographer who is helping me with this book – and a great help, too – who never drinks any water to speak of. She weighs 106 pounds … I wish you to note the difference in weight, and that water is a valuable thing for producing flesh as well as satisfying a normal thirst.”

There is a wealth of other information in Lovejoy’s book, including sections on common ailments and suggested treatments, breeding advice, and the making of home-cured pork products with the idea of promoting on-farm processing. His book is available online.

Article content