Since the European elections, the cards in circulation all give the same impression: that of a France almost entirely supported by the National Rally. All brown World and to Release, pink Figaro, blue, everywhere else. But each time, united, unanimous, entirely colorful, or almost, with the colors attributed to the party founded by Jean-Marie Le Pen and which came at the top of the ballot this Sunday.

Since their publication, these images have been everywhere, from social networks to cafe counters where many newspapers detailing the results have failed. Everywhere, at the risk of imposing itself in the minds of the French as an inevitability, an immutable fact. However, this is not the case: the reality, although marked by the undeniable progression of the extreme right, is much more nuanced, more complex than this apparent hegemony.

Most of these maps present the results by municipality. And each time only displays the camp which received the most votes in each of these localities. Effective, especially if you want to get an idea in a very short time of how your neighbors voted. But not without bias, far from it, especially in the context of a proportional election where each vote counts in the final verdict.

One color for multiple winners

Yes, Jordan Bardella and his team came first in 95% of the municipalities. A particularly evocative symbol and very well conveyed by this type of representation, which we understand in the blink of an eye. But, on the other hand, the score of the second and third places goes completely by the wayside. Were they 5 points behind Marine Le Pen’s colt or far behind? Impossible to know that way.

The National Rally has gained 2 million voters since the last European elections, in 2019, and continues to progress, from election to election. The dynamic is undeniable. But, looking more closely, from other angles, the brown tide that is emerging in all the newspapers of France is much less important than one might believe. Statistically, at least.

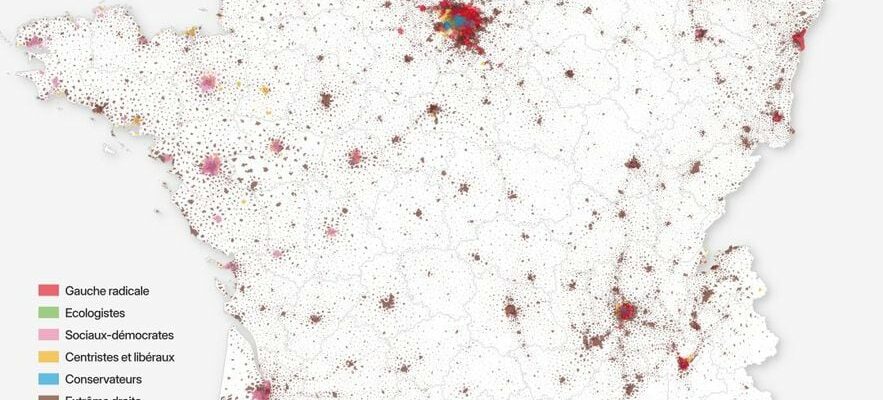

This is shown, among other things, by the numerous alternative maps which have flourished on social networks since the publication of the results. With, in the lead, that of Karim Douieb, a Belgian, doctor in computer science. It has been viewed more than 1.4 million times on Twitter. This doesn’t happen every day when we talk about electoral mathematics. Interactive, this visualization shows how by changing a few parameters, we can move from a homogeneous France to a much more sparse France.

In the Europeans, Jordan Bardella received around a third of the votes. It should, if we want to be representative, only cover a third of France. To get closer to these statistics, Karim Douieb decided to modify the dimensions displayed, and thus, to better take into account the weight of each municipality in the ballot. Suddenly the Ile de France, in the colors of Renaissance the presidential party, of Place publique, led by Raphaël Glucksmann or of La France Insoumise by Manon Aubry, swells. And the brown blisters of the RN are shrinking.

The cards change color

The person concerned had already printed such cards, in 2019 after the American elections. Trump then agitated for a red America, proof, according to him, that victory had been stolen from him. Karim Douieb’s adjustments brought back the blue of the Democrats and were widely used at the time. The specialist, founder of the visualization company Jetpack. HAVEhas since strived to point out: “The maps only show one aspect of reality. We must be aware of this, otherwise we can, for example, think that a party is unbeatable, too powerful, which is never the case. case”.

Cédric Rossi’s card is even less brown. The French cartographer’s technique, in “discontinuous cartogram”, gives more visibility to areas which count very little in the final result (in white), without inflating the RN vote. He is surprised that the media have, for the most part, opted for one and the same way of illustrating the distribution of votes. For him, “the only way to avoid bias is to multiply representations”. But he also recognizes that it is difficult to change the codes without disrupting the readership. If we had wanted to represent the electoral strength of the large cities as such, the latter would have covered half of the territory, thus eliminating many desertified countryside. Too unsettling, he told himself.

According to the maps, the brown tide is becoming much sparser.

© / Cedric Roussi

All these maps converge on at least one point: there is a gulf between the trends in the cities, all loyal to Republican values and parties, and those in the countryside, very much in favor of the National Rally. Here, again, this observation materializes more or less well, depending on the iconographic choices. “When we color everything in one color, we don’t really understand this divide,” underlines the expert. He is questioned in the middle of a mapping session. The specialist is working on a new image; he wants to feature every vote, not just the high scores.

No brown tide

Like this France which changes color in a few clicks, certain figures repeated from plateaus to terraces in recent days also need to be nuanced. If the National Rally has never had such a good score in the European elections, the party was already in the lead in 2019, during the last election to the Strasbourg Parliament. Jordan Bardella, already head of the list, then won 23% of the votes. In 2024, Jordan Bardella does significantly better, of course – he gains 8 points compared to the last election – but not enough to reflect the tidal wave highlighted on the maps that are circulating.

And this is far from the first time that the far-right party has been so convincing. This Sunday, 7.7 million French people came for him, it is true. But Marine Le Pen had attracted the support of more than 13 million French people in the second round of the 2022 presidential election, almost twice as many. Did she win over new voters, or were they simply more mobilized? Difficult to say, because these different ballots do not operate exactly on the same grounds and are therefore difficult to compare. But these figures show that if there was a surge, it hit France well before spring 2024.

The same goes for the rest of the European Union. “There was no surge, but a consolidation,” insists Gilles Ivaldi, political scientist and specialist in the far right. If nationalist and identity parties are making progress in France, Austria and Belgium, they have not escaped some disappointments, as in Finland, Hungary, Spain and Portugal. In total, these groups only grabbed a few additional seats. Around 5% more, according to provisional calculations by the researcher at Sciences Po. The wave was already here. It only grew a little bigger.

.