As each anniversary of the Normandy landings approaches, Jim Parks takes the time. Time to remember. Remembering your friends, their faces, their laughter, the moments spent together. But also, to remember that morning of June 6, 1944, when, barely 20 years old, he saw them fall on Juno Beach. This fine sand beach which borders the town of Courseulles-sur-Mer, which we had shown him many times in the days preceding “D-Day”.

From this day of fear, an image will never leave him, frozen in his memory. It is that of Corporal Martin, who died in the arms of his brother. “He was hit in the stomach, he died in a minute,” continues Jim Parks. “At that moment, so many things come to mind: his friends, his family, his journey.”

Eighty years have passed but the memories remain vivid. “Our boat was hit by a mine, we were thrown into the water, we had to swim to the beach, about 200 meters,” says Jim Parks who, to be accepted into the army, had lied on his age. Arriving on dry land, the young soldier realizes that he has lost almost all of his equipment. In front of him, a lifeless body. That of a soldier, whom he knows. “I took his helmet, his weapons and his ammunition and I went to fight.”

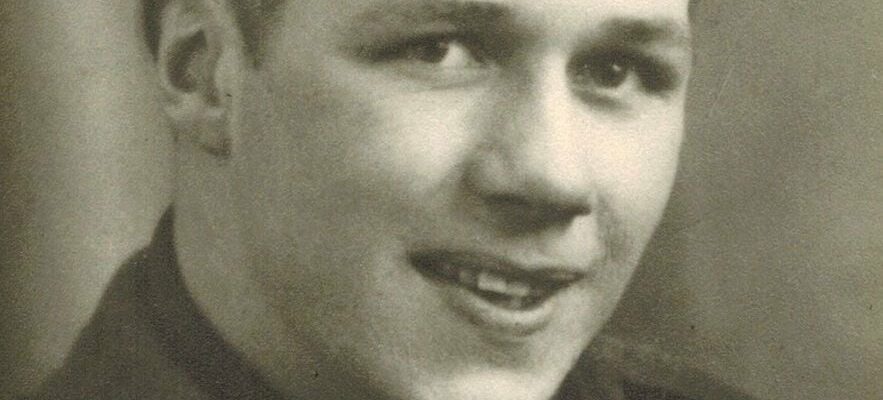

Jim Parks, veteran of the June 6, 1944 landings in Normandy

© / Family archives

Nearly 19,000 Canadian soldiers killed in Normandy

In total, more than 14,000 soldiers from the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division and the 2nd Canadian Armored Brigade landed on the French coast in the early morning of June 6, 1944. All volunteered to fight on the Old Continent . They all completed several months of preparation in England. Everyone waited with impatience and apprehension for this day which will be remembered as the day when the Allies liberated France from Nazi Germany. But not everyone has found their parents, brothers, sisters, wives and children who remained in the country. That day – “the longest day” – nearly 350 of them perished on the shore of Juno Beach. Canadian losses are estimated at nearly 1,000 for the day of June 6 alone and at 18,700 for the two and a half months of fighting in Normandy.

With its English garden appearance, the Bény-sur-Mer cemetery houses the graves of more than 2,000 Canadians who fell during the first weeks. “In Commonwealth culture, soldiers are always buried closest to where they died,” says Carl Liversage, head of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, an organization responsible for identifying and maintaining the graves of Commonwealth soldiers. Commonwealth states (South Africa, Australia, Canada, India, New Zealand, United Kingdom) died during the two world wars. This is the reason why the soldiers who died during the Battle of Normandy were never repatriated. “This place reminds us that Canadians, born thousands of kilometers from the French coast, agreed to risk their lives for our freedom,” underlines Pascal-Louis Caillaut, director of communications for the Commonwealth War Graves Commission.

A little-known role

This work of remembrance is all the more necessary as the role of the Canadian combatants during Operation Overlord remains little known, eclipsed by the role of the American and English armies immortalized in the cinema by The longest day (1962) or We have to save the soldier Ryan (1998). “Even Canadians tend to forget the role played by their compatriots in this war,” laments a Canadian woman on a pilgrimage to the Juno Beach Center, the Canadian museum of the landing beaches in Normandy. French political leaders also tend to neglect Canadian saviors. The rabbit posed by Manuel Valls to the organizers of the 70th anniversary of the Landing in 2014 left a bitter taste… “We experienced it as a humiliation”, summarizes Nathalie Worthington, director of the Juno Beach Center.

This lack of consideration is not new. “A long time ago, French political leaders only had eyes for the Americans,” recalls Michel Lebaron, former mayor of Cintheaux southeast of Caen in Calvados. The man who became president of the Juno Canada Normandy Committee – an association which works for the memory of Canadian soldiers – in 1992 had just celebrated his tenth birthday at the time of the D-Day landings. “When we heard the bombings at the school on the morning of June 6, we wondered what was happening, all communications were cut, he remembers. It was only in the evening that we learned that a landing had taken place.

Soldiers of the 9th Canadian Infantry Brigade disembark at Bernières-sur-Mer, June 6, 1944

© / Library and Archives Canada ZK 1083-3 Library and Archives Canada ZK 1083-3 / Courtesy Juno Beach Center Association

On his return from the Saint-Joseph Institute in Caen on June 10, he and dozens of other residents of his town witnessed a plane crash. At nightfall, he sees his father, equipped with food and civilian clothes, taking the road. A scene that will become everyday. One evening, while following him, the young boy ends up discovering that his father is hiding in a gabion – a shelter for a hunter – the Canadian paratrooper whose plane was crashed. His voice filled with emotion, Michel Lebaron remembers the words of his patriarch. “Be careful, don’t tell your mother, it’s a secret between you and me.”

“Because we owe them that”

Since his election to the Cintheaux municipal council in 1969, Michel Lebaron has moved heaven and earth “so that Canadian soldiers are not forgotten.” With the support of his friend and deputy for Calvados Michel d’Ornano, he initiated ceremonies of homage to the men who liberated his commune on August 8, 1944. At the beginning of the 2000s, he was also among the first and most fervent supporters of the Juno Beach Center which, step by step, immerses the visitor in the shoes of a Canadian soldier and presents the civil and military war effort of the Canadian population.

Nicole Hoffer, president of the Maison des Canadiens association

© / Amber Xerri

In Bernières-sur-Mer, the Hoffers have never deviated from their “duty” either. This is how, for more than thirty years, they have opened the door to this house, bought by Hervé Hoffer’s parents in the 1920s, on the edge of Juno Beach and which was first occupied by the Germans, then by the Canadians. One sunny afternoon, Nicole Hoffer, leaning out of her window, watches two children playing in the sand. One explains to the other: “A long time ago in this house there were bad guys. And the good guys came by sea and took the house.” Benevolent smile from the one who continues to keep this house alive despite the death of her husband in 2016. At L’Express, Nicole Hoffer, president of the association La Maison des Canadiens, sums up: “We owe them that, the Canadians give us liberated from a very harsh occupation, fighting for several months against sometimes fanatical enemies.

The bad luck of the Canadians

Operation Overlord is not limited to the day of June 6, 1944. It took the Allied forces more than two and a half months to rid Normandy of the “Boche” occupiers. “D-Day only marks the beginning of the fight for the Liberation of France. The clashes that followed were also bloody for our soldiers,” says the Department of Veterans Affairs Canada. “After the D-Day landings, Canadians had the misfortune of coming across the SS more than once,” reputed to be much more virulent than the regular army, explains John Desrosiers, director of international operations for the Canadian Department of Veterans Affairs.

Very close to Caen, the Ardenne Abbey is the Vico family home. The building was notably occupied during the Battle of Normandy by the 12th SS “Hitlerjugend” (Hitler Youth) division. “This one was Adolf Hitler’s favorite and therefore the most ferocious,” notes Jim Parks, whose childhood friend is among the many victims of these “Hitlerjugend”. After the liberation of Caen on July 19, 1944, one of the Vico children discovered the bodies of around twenty men in the garden adjoining the abbey. They are Canadian soldiers, taken prisoners of war by the SS and shot “in defiance of the rules of the Geneva Convention”, specifies Gabrielle Vico, wife of resistance fighter Jacques Vico, who disappeared in 2012.

At 95 years old, this pretty little lady who uses a wheelchair continues to pass on to young people and even “the less young”, the memory of the Canadians who fought during the Battle of Normandy. Like every year, she will be present at the ceremonies organized in their honor. Today, on the bloodied lands of Normandy, the battle that rages is a battle against oblivion.