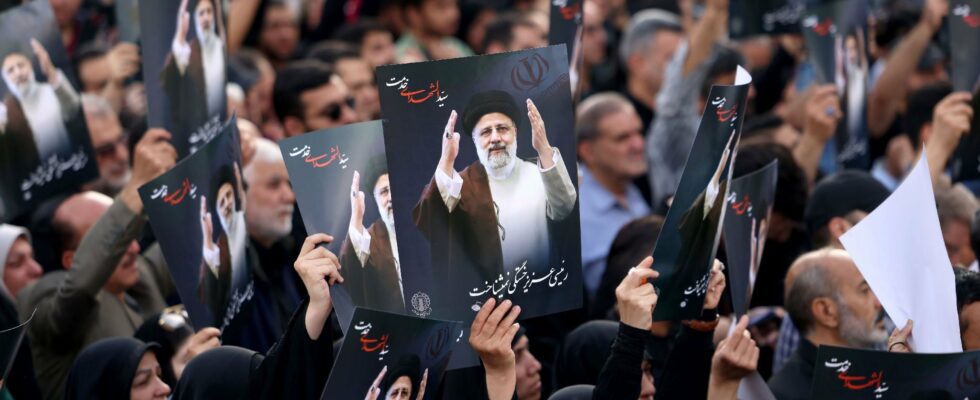

This Monday, May 20, Iran confirmed the death of President Ebrahim Raïssi in a helicopter crash, the origins of which are still unknown. Elected in 2021 in an election shunned by the Iranians, because it was a foregone conclusion, Raïssi was a discreet figure, but no less important in the Islamic Republic. This loyalist of Ayatollah Khamenei, whom many considered a serious candidate to succeed the Supreme Guide, was even an essential cog in the regime’s repressive apparatus.

Could the disappearance of Raïssi destabilize the regime and revitalize the heavily repressed civic movement in 2022? Arash Azizi, Iranian historian and journalist, doubts it: “After having protested, again, again and again, and after having suffered repression from the regime and hundreds of deaths, the Iranian civic movement is exhausted.” This is a pessimistic, but pragmatic observation that L’Express delivers the author of What Iranians want: Women, Life, Freedom (Oneworld, 2024), which is waiting to see which candidates will be allowed to run in the presidential election scheduled for June.

L’Express: Who was Ebrahim Raïssi ?

Arash Azizi: It’s simple, I think that no other leader of the Islamic Republic has had as much blood on his hands as Ibrahim Raïssi. He dedicated his life to serving the regime, and he did it in the bloodiest way possible. In the 1980s, his work within the judiciary resulted in the execution of thousands of Iranians, and I am talking about extrajudicial executions. In 1988, for example, he was responsible for killing thousands of political prisoners, most of whom were left-wing opponents.

As president, he led a politically repressive, internationally isolated and economically impoverished Iran. It was he who oversaw the repression of the “Women, Life, Freedom” movement (Editor’s note: slogan chanted during the demonstrations following the death of Mahsa Amini, in September 2022), which left more than 500 dead and numerous executions.

Despite its brutality, it was relatively spared by the demonstrators of the “Women, Life, Freedom” movement. How do you explain that ?

Politically, Raïssi did not have a very striking stature, he was a sort of “yes man” of Ayatollah Khamenei, he was totally docile to him. He sorely lacked charisma, we dozed off during his speeches. It is also interesting to note that in the posthumous tributes, it is mainly his loyalty to Khamenei that has been praised. Raïssi was therefore as brutal as he was politically insignificant.

It is true that he was not the main target of the demonstrators, even if he was criticized. For example, when he visited Kurdistan right in the middle of the movement, in the town of Sanandaj, there were calls for a boycott and not to go out on the streets when he was there. But overall, he was not at the heart of the discussions, quite simply because he did not appear to be a politically important figure, because power was located elsewhere, and also because his brutality was mainly exercised in the 1980s, so for many people it’s distant.

How is Iran doing at the time of its disappearance?

Overall, in many ways, Iran under Raisi has never been in worse shape. Iran is currently in a political impasse. Presidential elections in Iran were never free and fair, but they were competitive. This was the case for the elections of Mohammad Khatami, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, Hassan Rouhani, between 1997 and 2017. But during the election of Raïssi in 2021, the absence of real electoral competition resulted in a record abstention, because the Iranians knew the results were decided in advance. It therefore had no popular and democratic legitimacy.

Internationally, Iran is more isolated than ever and suffers from a set of very extensive sanctions that hit the middle classes hard. We can, however, credit Raisi with the reestablishment of ties with Saudi Arabia, and the fact that Iran joined the Brics and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization. All this is important for the country. But this marks the consolidation of an international strategy turned towards the East, characterized by the strengthening of Iran’s links with Russia and China to the detriment of its relations with the West.

Finally, Raisi’s death comes when Ayatollah Khamenei is 85 years old, and the question of succession is increasingly pressing. For Khamenei, it is very important to leave the regime in good hands in order to preserve the ideals of the Islamic Republic after its disappearance.

Was Raïssi seen as a potential successor?

I wouldn’t say that Khamenei had chosen Raisi as his successor, and it is very difficult to know what the ayatollah really thinks. On the other hand, Khamenei’s concern for the question of succession is real, and the position of president plays an important role in this regard, because whoever occupies it could be a serious candidate for succession, or at least he will play an important role in Khamenei’s death.

What is the role, in Iranian institutions, of the President of the Islamic Republic?

The president’s powers are very limited, and most important decisions are made by the Supreme Leader. In the Constitution, the president is the head of the executive, he takes care of the current affairs of the country, he plays an important role in the economy… But 70% of the powers are in the hands of the Supreme Guide. In practice, Khamenei has succeeded in encroaching on the president’s power and today takes care of much of what should be the prerogatives of the head of state.

For example, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs technically reports to the presidency. However, some of the ministry’s most important functions, such as embassies in key countries such as Syria, Lebanon and Yemen, are run by the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, a militia that Khamenei leads. However, the role of president remains important politically, particularly in the power struggles between the different factions.

Mohammad Mokhber has been appointed interim president, and elections are to be held on June 28… What can we expect from these elections?

These elections will not be free and fair, as no election in the Islamic Republic has ever been. Not everyone can show up. For example, if I wanted to run, I couldn’t do it, just like all liberals, democrats, left-wing progressives, etc. The real question is therefore the following: will it be an election like that of 2021, in which the results will be known in advance, with a single candidate surrounded by candidates selected by those in power to make up the numbers? Or will it be a real competition between the different tendencies of the regime, of which there are three: the supporters of a hard line, the conservative centrists, and the reformists.

Technically, the Council of Guardians (Editor’s note: a sort of Constitutional Council), which is composed in particular of six jurists appointed by the Supreme Guide, must decide who is able or not to present themselves. In reality, it is Khamenei who decides, because the members of the Council listen to him and are very loyal to him. Many people see the upcoming election as an opportunity to broaden the regime’s base by holding truly competitive elections. Will Khamenei and the members of the Guardian Council listen to them? We will see…

Why will the chosen candidates influence the outcome of the election?

Because each of the trends has key personalities, popular with citizens. Let’s take a French example. If La France insoumise is allowed to compete in a presidential election, but Jean-Luc Mélenchon is prevented from running and replaced by a little-known deputy, then the party will obtain less support than if it were the natural candidate.

“At the moment, there is very little enthusiasm around the next presidential election.”

In Iran, it’s the same thing. Personally, I would prefer it to be a reformer who wins the election, because they are the ones who have the strongest commitment to liberal democracy and who are the most progressive. But if you present Majid Ansari instead of Mostafa Tazjadeh, I don’t think I will vote for them. Ansari is a reformer loyal to the regime, he was even nominated by Khamenei to the Council for Discerning the Best Interests of the Regime (Editor’s note: institution that can be compared to the Council of State). He would be an ideal candidate for the Ayatollah, but he would be uninspiring for voters…

Mostafa Tazjadeh, on the other hand, is a popular opposition figure, he has been in prison for defending democracy, and in 2021 the Guardian Council did not let him run. If he were to run, I would support him, but there is very little chance that that will be the case… We will know by June 11 or 12 the final list of candidates authorized to run. But at the moment, there is very little enthusiasm around the upcoming presidential election.

Could Raïssi’s death destabilize the regime, to the point of seeing new citizen protests emerge?

You know, the regime has always feared the eruption of a new citizen protest. During moments of crisis, this is when they are most likely to explode. But I don’t think that’s a likely outcome. After protesting again, again and again, and after suffering regime repression and hundreds of deaths, the Iranian civic movement is exhausted. In reality, to hope for a change in the Iranian regime, we would need a strategy that is not limited to going out and protesting in the streets, but a clear political translation. What we need is for the opposition to organize itself with real political leadership at its head.

Opposition figures, whether abroad or in Iran, must find a way to build a viable political alternative. This can involve, for example, agreeing to make compromises by agreeing on a common democratic vision. So far, they haven’t done it and the last time they tried, it ended in a fiasco. Five or six members of the opposition had tried to form a sort of coalition, which collapsed after only a few weeks, due to too deep disagreements…

Where we can be optimistic, however, is that the failure of the Islamic Republic’s policies cannot last forever. After Khamenei’s death, it is not impossible that we will see changes in the regime and the policies pursued. This will not necessarily result in a strong democratization of the regime, but we can at least hope for an opening on the international level, as well as a reduction in political repression.

Should the international community do something?

Economic sanctions policies have not been effective in my opinion. But the international community can do something, for example by supporting the Iranian civic movement and putting pressure on the political opposition to take responsibility. The reality is that most Western countries do not consider the Middle East a priority. But we cannot wait for change to come from the international community. Change must come from the Iranians themselves.

To have international support, there must be something to support, namely, a real and well-organized political opposition, capable of proposing a democratic alternative to the Islamic Republic. This is not yet the case, but the Iranian civic movement is very important and offers a basis on which to build this alternative.

.