Between a region affected by flooding and another affected by historic drought, there are only a thousand kilometers. Paradoxical and striking effect of an ever more disrupted climate, and growing tensions on the country’s water resources. Each summer now imposes its debate on its uses and access, while the sometimes torrential rains of winter ravage certain territories. How can France adapt to this new reality? L’Express wanted to contribute to a debate that is more necessary than ever. These six “black scenarios” for water by 2030 are the translation. They are neither forecasts nor predictions. But hypotheses on which public and industrial authorities are already working more or less directly, and whose frameworks have been refined and enriched by the forty experts interviewed: researchers, meteorologists, senior civil servants, engineers, insurers… All are unanimous: the The country’s resilience in the face of these events is being built now.

EPISODE 1 – March 2026, the 100-year flood of the Seine devastates Paris: our dark water scenarios

EPISODE 2 – August 2027, a mega-fire in Hérault: the worrying hypothesis of an “overrun”

EPISODE 3 – January 2026: a dangerous weather cocktail savagely hits the north of France

EPISODE 4 – August 2029: several scorching summers fuel tensions on the Rhône

EPISODE 5 – December 2025: a tropical storm and a cyclone hit Reunion Island

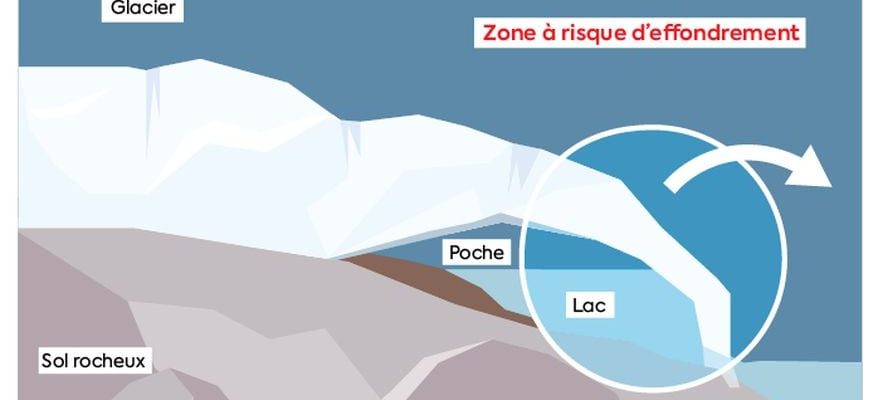

It is 11:30 p.m. when the shrill cry of a siren fills the hamlet of Bionnay. Two seconds of alarm, three seconds of silence. In these houses located at the bottom of the valley, three kilometers from the center of Saint-Gervais-les-Bains, in Haute-Savoie, the alarm is well known to the inhabitants who no longer pay attention to it: as with the firefighters, it rings every first Wednesday of the month. On this night in July 2028, it is not an exercise: 300 meters higher, the Tête Rousse glacier has just collapsed. Under the effect of the melting, a pocket of pressurized water of 50,000 cubic meters gave way. In a few minutes, a phenomenal quantity of ice and rock tumbles down the rocky slopes of the Pierre Ronde desert and reaches the Bionnassay torrent, which suddenly swells. A “torrential lava” carries rocks and trees and reaches the first homes.

Here, almost 1,000 people live and come on vacation. Many are already asleep, and few leave their homes. They are the first affected when the icy magma hits. Emergency actions and refuge areas located at height have been forgotten. “As long as a risk has not occurred, the population no longer believes in it, so knowledge of the risk has completely evaporated,” laments Jean-Marc Peillex, the mayor of Saint-Gervais. He remembers an alert episode in 2015 during which very few residents mobilized to respect safety instructions. This time, the flood carries everything in its path. Houses, cars, power lines disappear in a deafening roar. The flood continues its route along the watercourse, before slowing down a few kilometers further on, still managing to flood the Fayet area. In the aftermath of the disaster, the toll was heavy: between 2,000 and 3,000 victims.

© / The Express

No consideration in prevention plans

The glacier was, however, watched over like milk on fire. In 1892, a similar disaster struck the area. At the time, 200,000 cubic meters of ice and water had flooded the valley, which was still sparsely populated; 17 houses and a thermal establishment were destroyed, killing nearly 250 people and leaving major trauma. In 2010, a team of scientists observed a new pocket of water of around 60,000 cubic meters in the bowels of the glacier. “We were in an absolute crisis situation: the water under pressure threatened to explode,” remembers Christian Vincent, research engineer at the CNRS and specialist in risks of glacial origin. The Tête Rousse glacier was subsequently dotted with sensors, and had been drained multiple times. But a new pocket was observed in 2024. Located in an area difficult to access, its surveillance was less. It is the latter which could have caused the breakup. Scientists believe that climate change could have played a role, but nuance: the complex dynamics of the glacier remain difficult to understand.

The scale of the disaster also reflects the urbanization of the mountain. Without rules prohibiting construction, houses flourished next to the watercourse. “The risk prevention plans did not take into account the disaster of 1892”, notes Christian Vincent, who tempers: “When we look at the similar risks in the region we could close all the Valleys”. The probability of a disaster being considered very low, it had not been taken into account in the prefecture’s plan for the prevention of major foreseeable risks (PPR). Glacier monitoring, alert mechanisms and pumping measures also provided a reassuring framework. “The most difficult thing is not to detect the hazard, it is to know if it constitutes a risk,” concludes Christian Vincent.

.