Two hundred years of military non-alignment coming to an end. This Thursday, March 7, Sweden officially joined NATO, becoming its 32nd member after long months of negotiations, notably with Viktor Orban’s Hungary. Until a few years ago, however, Stockholm’s membership in the Alliance was seen as an impassable red line in Swedish society, marked by two centuries of neutrality. But February 24, 2022 changed everything, when Russia launched Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, illustrating the Kremlin’s appetite for Eastern Europe.

This entry of Sweden into NATO, combined with that of Finland in April 2023, completely reshuffles the cards in the region. Beyond the notable military and industrial strength that the Kingdom represents, there are also geographical issues that are being largely shaken up. From the Baltic Sea to the Arctic Ocean, L’Express looks back on the various military and political issues in the region that this accession involves.

The Baltic Sea, the “NATO lake”?

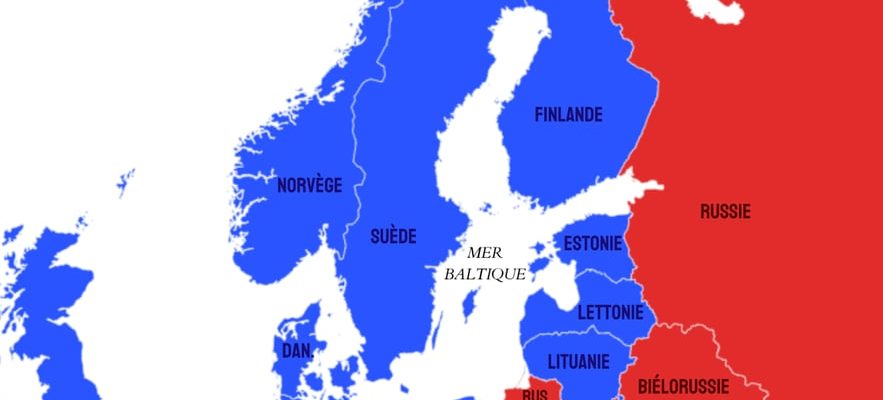

This is perhaps the main conclusion made by most military experts. With the accession of Sweden – as well as that of Finland this year – to NATO, the Baltic Sea would now be almost entirely bordered by member countries of the Alliance.

One territory is particularly strategic: the island of Gotland. Belonging to Sweden, this island of more than 3,000 km², remilitarized since 2018, is the real gateway to the north of the Baltic Sea. Controlling this island ensures that NATO makes it virtually impossible for Moscow to transport ships from north-west Russia. An advantage: already in 2022, Stockholm had announced nearly $163 million in investments to strengthen its military presence in this territory.

Map of NATO member states in Eastern Europe after Sweden’s accession.

© / The Express

Would the entire Baltic Sea be controlled by NATO? No, because a pocket of Russian territory still resists the transatlantic military alliance: the slave of Kaliningrad. Located between Lithuania and Poland, this “Russian island” in the heart of Europe, very heavily armed, is at the heart of all escalation scenarios by European military headquarters. One, in particular, is monopolizing the attention of the NATO armies: a joint attack coming from Belarus and Russia – via Kaliningrad – on the Suwalki corridor, the name given to the 65 kilometer strip of land which separates the Poland from Lithuania. An operation which would cut off the Baltic countries (Estonia, Lithuania and Latvia) from the rest of the Alliance, and which is particularly worrying in Eastern Europe.

Sweden’s accession allows NATO to further lock down northeastern Europe, providing maritime and military support for NATO, as well as a possible highly strategic transit point. Swedish Prime Minister Ulf Kristersson already declared in January that his country was ready to provide troops to NATO forces in Latvia.

A military heavyweight

Who says non-alignment, says military independence to be ensured. Sweden has long invested massively in its defense in order to ensure its neutrality, before gradually reducing its spending after the end of the Cold War. But starting in 2014 and Russia’s annexation of Crimea, the Kingdom’s defense spending began to increase again. So much so that the Swedish government now ensures that NATO’s objective of spending 2% of GDP on defense will be reached again in 2024. Currently, Sweden has a little more than 14,000 active soldiers, to whom we can also add nearly 10,000 reservists.

Above all, Sweden has a powerful military industry, notably through the Saab defense group. “The war in Ukraine has caused a great awakening. Today we must be able to face a potential aggressor, and not just hope that nothing will happen”, explained Micael Johansson, CEO of Saab, to L’Express a few weeks ago. The industrial group hopes, for example, to quadruple its production of anti-tank munitions by 2025, to reach 400,000 units per year.

In the air, the Swedish army can rely on just over 90 JAS 39 Gripen (Saab) fighter planes, a popular model also sold to Hungary, Brazil and South Africa. In the Baltic Sea, Stockholm’s war fleet is also large, including several corvettes and submarines.

The Arctic, a contested future El Dorado

These may not be the very concrete strategic implications of the Baltic Sea. But here too, Sweden’s membership in NATO directly impacts another geopolitical issue which promises to be crucial in the years to come: the Arctic. Russia claims to want to make this ocean a strategic asset, both to develop alternative trade routes with global warming and to ensure military control, while 50% of the coasts of the Arctic Ocean are located on Russian territory.

Sweden’s membership in NATO, however, has partly shaken up the balance of forces. The Kingdom of Sweden is notably one of the eight member countries of the Arctic Alliance, an intergovernmental forum dealing with strategic issues in the region. Eight countries make it up, of which… seven are now part of NATO (United States, Canada, Denmark, Norway, Iceland, Finland and therefore Sweden); the last therefore obviously being Russia. Enough to further reduce Moscow’s room for maneuver, with Swedish territory now able to serve as a real rear base for NATO.

Because the Arctic is also at the heart of Swedish concerns. Swedish intelligence services (Säpo) recently warned of the territorial threat posed by Russian espionage. Russia, but also China, “carry out activities that threaten security in the far north of Sweden,” Säpo wrote in its annual threat assessment report. “Russia’s interest in northern Sweden mainly concerns Swedish military capabilities,” Swedish intelligence continued.

“Countermeasures” announced by Moscow

A sign of the concern that Sweden’s accession to NATO represents for Moscow, the Kremlin’s reaction was not long in coming. As soon as Hungary’s ratification was announced on Monday February 26, the last obstacle blocking Stockholm, Russia announced that it would take “countermeasures of a political and military-technical nature in order to minimize the threats that weigh on its national security.

Their content “will depend on the conditions and extent of Sweden’s integration into NATO, including the possible deployment in this country of troops, means and weapons” of the Atlantic Alliance, had broadcast on his Telegram channel the Russian Embassy in Stockholm. “It is up to Sweden to make a sovereign choice on its security policy. At the same time, Sweden’s entry into a military alliance hostile to Russia will have negative consequences on stability in Europe of the North and around the Baltic Sea which remains our common space” and which will never become a “NATO lake”, Russian diplomacy asserted.