In the stands of the Stade de France, the spectators hold their breath. Whatever happens, this evening of August 4, 2024 will remain in the legend and they know it. Below, on the ocher-colored track, ten sprinters are preparing to conquer the Grail just 100 meters further. Less than ten seconds later, the new champion raises his arms. The image makes the A newspapers around the world. After a series of interviews, the athlete received his gold medal the next day and signed dozens of sponsorship contracts. In the meantime, he has met certain obligations, including the famous anti-doping control. The verdict is negative. Glory to the new hero! However, we will have to wait ten years, 2034, for all doubt to be definitively removed. Athletes’ samples are in fact kept for a decade and tested again at that time, in case scientific advances reveal cheating. Welcome to the new reality of sport.

Flashback: London Olympics, 2012. Nine athletes tested positive during the competition, a relatively low number. Ten years later, in 2022, the reality is quite different: 73 anti-doping rule violations were noted after new analyzes of 2,727 samples; 31 medals were withdrawn and 46 reallocated. Certainly, these Games were hit hard by the Russian state doping scandal, but the observation is bitter.

Will the Paris 2024 Olympics manage to avoid such bad publicity? The Organizing Committee (Cojop) and the global anti-doping community have been refining their arsenal for several years now. “The fight against doping does not take place once every four years, it is a constant battle, considers Olivier Niggli, Director General of the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA). is to catch all cheaters before July 26, not during or after the Games.” But how to recognize them? According to the texts in force, doping corresponds to taking one or more substances included in the list of prohibited products. Three criteria are necessary to be included: that these substances are dangerous to health, that they improve performance, and that they are contrary to the spirit of sport. Meeting two of these criteria is enough to be present on this list. Among anabolic agents or peptic hormones, there are also drugs whose use can be misused, such as Ibuprofen. Last September, the WADA Executive Committee added tramadol.

To avoid any scandal, a plan for testing athletes likely to participate in the Olympic Games has been put in place by the International Olympic Committee (IOC), the International Testing Agency (ITA) and WADA, with a potential pool of 100,000 athletes established one year before the event. This is refined over the months depending on the sports – wrestling or weightlifting being more at risk than archery or table tennis -, the qualified, the injured or the nationalities: certain States have a strong history of doping, like Russia, Belarus or Ukraine. In detail, around 10,000 athletes are currently considered “at risk” and monitored very closely. All will be tested three times in three weeks before the Games to compete. For this, they must be locatable 24 hours a day, seven days a week. “It is a very strict regime, it is very intrusive. If we want to be provocative, we would say that they are almost more monitored than people suspected of terrorism!”, highlights David Pavot, professor of law and holder of the Research Chair on anti-doping in sport at the University of Sherbrooke, in Canada. However, some manage, again and again, to get around the obstacles. During the Beijing Winter Olympics in 2022, Russian skater Kamila Valieva tested positive for trimetazidine. Suspended for four years last January, she was one of the athletes regularly monitored by the AMA and the ITA.

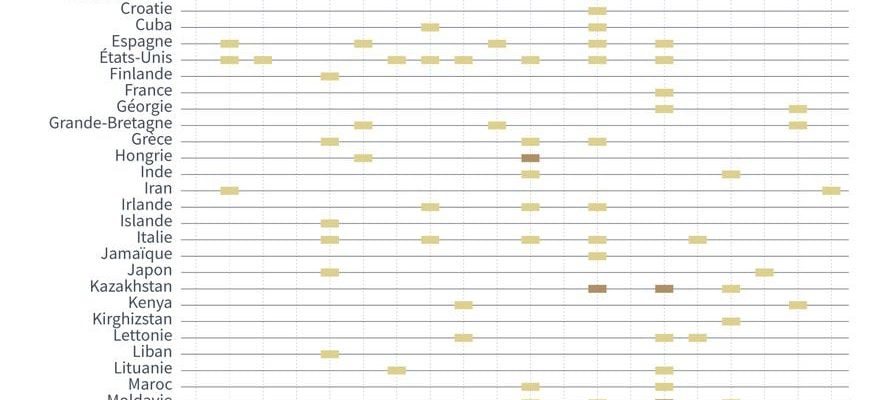

Number of doping cases recorded by country at the Winter and Summer Olympic Games since 1968.

© / SABRINA BLANCHARD, BERTILLE LAGORCE / AFP

“It has become very complicated to take drugs”

During this summer’s Olympics, organization will be key. Nearly 300 control officials are gradually being trained by the French Anti-Doping Agency (AFLD), which will act under the aegis of the ITA. Condition sine qua non : practice a medical or paramedical profession or be a judicial police officer, and speak English correctly. They will be helped by 600 “chaperones”. Because the task is immense: in the summer of 2024, nearly 6,000 tests will have to be carried out for the Olympics alone, or almost half of what France usually carries out in a year. In terms of equipment, adapted toilets or mirrors to see the athletes must be installed in the numerous sampling stations. Once the athlete is inside, everything is very regulated, far from the Epinal image which would like the procedure to be carried out on the corner of a table: “Open the bottle, fill it, close it, put it in the cardboard box, place the box in the plastic bag, seal the plastic bag”: these words will be spoken by the control agents who do not handle any object directly. It is then up to them to regularly check the name of the athlete being tested, the sample number, note the volume of urine collected, and scrupulously complete the form.

However, it can happen that the targeted person is stressed and becomes blocked. You have to imagine that it is not easy to relieve yourself in front of one or more people right after a race, a match or a fight. Especially since almost 80% of the tests carried out during the competition are urinary. In this case, if the required volume of urine – 90 milliliters minimum – has not been collected, the first sample must still be sealed, then reopened in order to mix it with the second and thus obtain the two samples A and B which will be tested. Apprentice “samplers” must also be trained in blood sampling procedures, as well as the new method of collecting dried blood drops put in place since the Tokyo Olympics in 2021. “Today, the tools at our disposal “The provisions are much broader than ten years ago, and the targeting is much more effective, continues Olivier Niggli. In other words, it has become very complicated to take drugs.” Complicated, but not impossible.

Modern doping, an air of deja vu

And the news proves it. “For ten years, 27,000 athletes have tested positive, or 7.5 per day,” argues Raphaël Faiss, research manager at the University of Lausanne. And yet, there are only 0.6 to 1% of abnormal samples out of all those taken each year according to the AMA. “It’s very little, but it’s perhaps the tree that hides the forest because many more, in reality, use doping products. It is estimated that between 10 and 30% of athletes have already used them. in their careers, with nationalities and sports more concerned than others”, continues the researcher. Suffice it to say that the fight is far from over. “The mass doping that we experienced in the early 2000s, during the era of Lance Armstrong, seems to be over, it is no longer the Wild West but there is still a lot to do,” adds David Pavot.

Vestiges of the past, anabolic steroids, including testosterone, are still widely used by some athletes [NDLR : le footballeur Paul Pogba a été récemment suspendu 4 ans après une contre-expertise]. This hormone helps produce muscle, but also accelerates muscle recovery and plays the role of psychostimulant, increasing motivation and the desire to succeed. Another advantage for cheaters: it is naturally produced by the human body, therefore difficult to detect during checks. “The development of biological passports for athletes, who celebrate their 15th anniversary this year, has made it possible to better target those whose values vary abnormally,” continues Raphaël Faiss.

This electronic document is based on monitoring selected biological variables over time, as opposed to the traditional direct detection of doping through analyses. And the researcher continues: “Modern doping has actually changed little, the substances are essentially the same. Only, the doses administered have been generally reduced and more targeted.” Does a miracle substance exist? “We currently have no trace of such a product, but you never know!” insists David Pavot. Here again, scientific progress makes it possible to reduce the extent of doping. “Let’s make a comparison: around fifteen years ago, we were able to detect a bathtub in an Olympic swimming pool. Today, we can see a teaspoon in two Olympic pools,” continues the researcher.

A budget in question

One question remains: does the World Anti-Doping Agency have the means to fight effectively against these practices and these developments? WADA’s budget is currently $54 million. A very modest sum to which must be added the budget of each national anti-doping agency and the international federations. “This is the annual salary of a basketball player when the market for dietary supplements in sport is around 30 billion dollars,” laughs Raphaël Faiss. For comparison, “human” anti-doping agencies carry out around 300,000 tests on athletes each year, compared to 650,000 carried out in 2019 on racing horses by equestrian federations…” But Olivier Niggli wants to be reassuring: “The system will be very efficient at the Paris Olympics. Let’s hope that the athletes will make the right decisions.” Raphaël Faiss also wants to maintain hope: “This system is imperfect but necessary to offer honest athletes a chance to win.” And David Pavot concludes: “There will always be dopers; just as there will always be thieves in society. We must educate athletes from a very young age by targeting athletes who are already adults, and make these most difficult practices possible.

From there, how can we measure whether or not the Paris Olympics will be successful? If many tests came back positive, the news would be terrible but would mean that the fight against doping is working, and that cheaters will be punished. Conversely, would it be a success not to count a single case of doping? This could mean that there are holes in the racket or, in the worst case, that the athletes have found a solution. Insoluble equation. We still have to wait… 2034.

.