Has humanity disappointed René Perrot? Everything points to this from the study of the second part of his life. At the beginning of the 1950s, at the age of 40, he isolated himself from his contemporaries and gave up representing the human figure in favor of the nature that surrounded him. Animals, plants and minerals then populate his tapestries, the preparatory drawings of which bear witness to careful observation of the fauna and flora. But it was not always like this, as detailed in the retrospective that the Mucem devotes to the man from Doubs, under the curatorship of Raphaël Bories and Marie-Charlotte Calafat, curators at the Marseille museum, and Alice Bernadac , of the International Tapestry City. Under the title My poor heart is an owl (a verse by Apollinaire taken up by the artist in one of his wall works), nearly 200 drawings, paintings, woven productions and objects, brought together for the first time, shed light on the career of a creator as prolific as singular.

René Perrot was only 2 years old when his father, a schoolteacher, was mobilized in 1914. The four years of his father’s absence during the Great War had a lasting impact on him. Having become a poster artist after training in Decorative Arts, his first colorful creations were in the style of the 1930s, reflecting his taste for the circus, a popular entertainment in the capital, even if, at the same time, the convinced antimilitarist rebelled against the rise of Nazism and fascism which threaten peace in Europe.

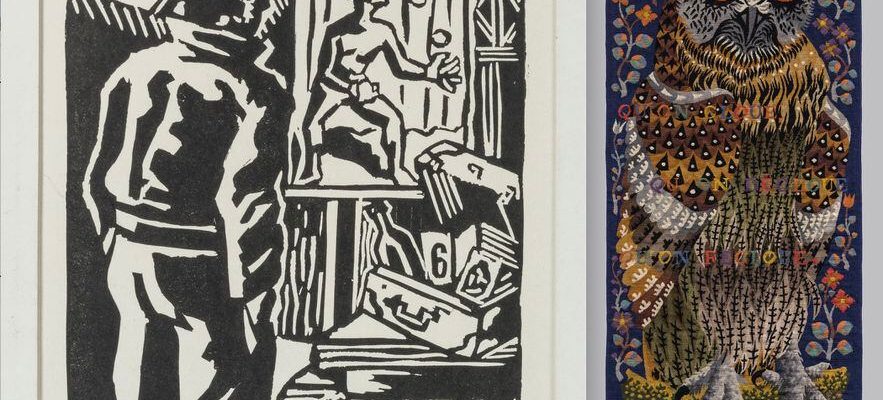

René Perrot, “Le Départ”, Paris, 1939. To the right. : “My poor heart is an owl”, Felletin, 1963.

/ © Adagp, Paris, 2023 / Nicolas Roger

When the mobilization hit him in 1939, Perrot denounced the absurdity of the conflict in explicit engravings: one of them shows him on the eve of his departure facing the unfinished canvas depicting a juggler which he will not finish not when he returns. He spent most of his war at the National Museum of Popular Arts and Traditions, the ancestor of Mucem, where he worked as an investigative artist in the French countryside to document crafts and traditional ways of life. Combined with his fear of seeing the industrial revolution sweep away these ancestral customs, his interest in the land and folklore worked wonders during his ethnographic wanderings in Franche-Comté, Cantal and the Pyrénées-Orientales.

After the war, René Perrot was part of the revival of tapestry which rejected the copy of painting in favor of creations specific to the genre. In the wake of Jean Lurçat, he created hundreds of numbered boxes from which tapestries were made for the Felletin, Aubusson and Gobelins factories. Among them, a number of State orders transiting through the Mobilier national adorn official buildings across the planet, hence Perrot’s international notoriety in the field.

A very paradoxical visibility since the artist lives removed from the world, with a predilection for nocturnal birds of prey, those unloved animals of the bestiary, which he reproduces in dazzling and poetic compositions, like this ode to the passing of time , where the years are measured by the rings of a trunk seen in section, the seasons by the vegetation in the corners, the months by the 12 flowers on a blue background, the days by the cycle of the moon. Alongside Perrot for a long time there was Grisette, a tame little owl about whom he was inexhaustible during the few interviews he gave during the last years of his life. When he died in 1966, his friend Raymond Coulon sculpted the animal on his grave.