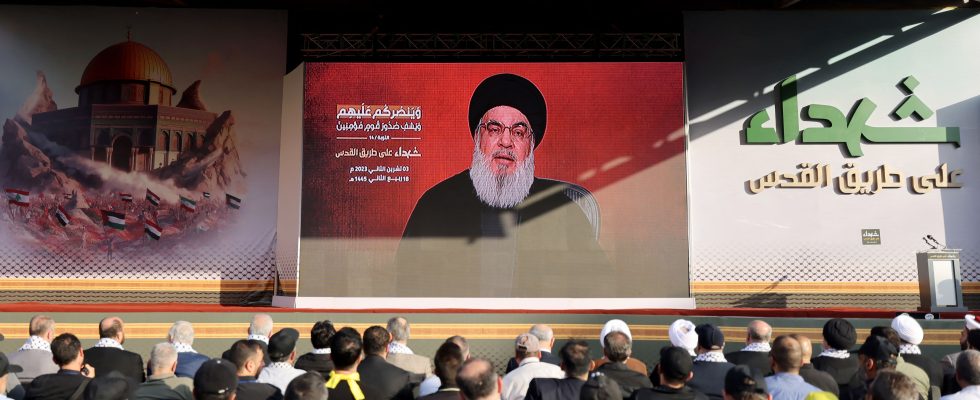

Much ado about not much. From the southern suburbs of Beirut to Nabatiyé, in the south, thousands of Hezbollah supporters gathered on Friday, November 3 under yellow flags, waiting for a single slogan… which did not come . Because the long-awaited speech by the secretary general of Hezbollah, Hassan Nasrallah, supposed to shake things up, ultimately turned out to be very lukewarm. The leader of the Shiite party, a protégé of Tehran, who has remained silent since October 7, has clearly put the brakes on a broader engagement of his militia in the current sequence.

He was expected to become commander-in-chief of the “Axis of Resistance”, the name given by Iran to groups and states that oppose Israel. On the contrary, he did almost everything to avoid putting on the costume, denying any involvement in the bloody Hamas attack and contenting himself with fairly vague threats aimed at Israel and the United States. If he raised his voice by declaring that all options are on the table, he linked potential action on a larger scale to the evolution of the situation in Gaza or to an Israeli offensive on Lebanon.

His speech could thus be summarized in two ideas: “I will only wage war if it is imposed on me”; “Hamas achieved an exploit but I have nothing to do with it.” Proof of his desire to distance himself from the operation carried out by his Palestinian ally, Hassan Nasrallah went so far as to take up conspiracy theories which accuse the IDF of being responsible for the deaths of Israeli civilians.

Are Hassan Nasrallah and his Iranian godfather afraid of an escalation which could place them in the direct sights of the United States? Probably. The party has already lost 57 fighters in less than a month in a war that still has no name. But this is not the only reason which explains its relative restraint. THE sayyed knows that the Lebanese do not want a new war and may not forgive him. He also knows that, for the moment, Iran is in a position of strength and that it has no interest in taking risks that could cause it to lose much more than the gains made so far. He further believes that the Israeli army will not be able to achieve its objectives in Gaza and that Hamas’s trap is turning against it.

Hassan Nasrallah must find a delicate balance between his support for the Palestinian cause, the essence of the “Resistance”, and his desire not to weaken his gains in Lebanon and the region. He wants to exist, without being on the front line. For the moment, the strategy is rather paying off. He can boast of forcing Israel to mobilize part of its army on its northern border. He can sense that the Arab world is in turmoil and that he and his Iranian godfather will be able to ride this anger for years.

But Hassan Nasrallah’s bet is based on the fact that the Israeli army will fail. What if he was wrong? And if the IDF succeeded in destroying Hamas in Gaza, what would Hassan Nasrallah do? What if he was caught in his own trap?