By Darragh McKeon, trans. from English (Ireland) by Carine Chichereau.

A sensitive dive into the Irish conflict

© / Belfond Editions

The former sociology student and rugby player, theater director and director, knows how to take his time. After a fantastic first novel, retracing the journey of four characters affected by the Chernobyl nuclear disaster (Everything solid dissolves in air), published in France in 2015, here is his second novel, Remembrance Sunday. However, the Irishman has not been idle between the two: he has just completed his first feature film, shot in Barcelona, but also and above all he threw an entire manuscript into oblivion two years ago, as he tells us tells him about his visit to Paris. “My first draft was boring,” he confides, “it took place within the Irish community in New York, where I was living at the time. At the same time I was volunteering in a hospital, working with the sick at the gates. of death. Listening to them, I was impressed by their perception of time, by the dilation of it. The Northern Irish tragedy came to mind. I did not dare approach it, for an Irish writer, from the South at that, it’s a real cliché.” May Darragh McKeon rest assured, his Remembrance Sunday is not a cliché. It says everything about the fractures and the heaviness of Ireland at the time with, in focus, the IRA attack of November 8, 1987, in Enniskillen, in County Fermanagh, during Remembrance Sunday, making, 10:43 a.m. exactly, eleven dead and seventy-three injured (all civilians).

His hero, Simon, experienced this attack firsthand, at the age of 15. He is now 49 and lives in New York. He has just separated from Camille, his French partner, meets by chance the piano teacher from his childhood and suddenly has an epileptic attack, like the ones that fell on him shortly after the attack. The past comes flooding back, guilt returns to torment him: while he was camping on the small island of Lough Ene, in the same year 1987, he had witnessed the landing of men who had probably come to hide something and one of between them had told him to keep quiet. If he had spoken, could the worst have been avoided? And to imagine the trajectory of this man encountered at night on the island… It gives him an identity, son of a cattle breeder and a teacher, married to a Protestant nurse, and a function, worker on the docks of Belfast, and finely describes the process of radicalization of this placid worker, from involvement with the IRA to indiscriminate violence, all in a country paralyzed by fear. Belfast then resembles a prison, the hunger strike of the inmates of Maze prison, including a certain Bobby Sands, hardly moves an indifferent Margaret Thatcher, and yet the end of the “Time of the Troubles” is approaching. Thanks to Darragh McKeon, who skillfully deciphers the roots of evil, we better understand this fratricidal conflict, both so close and so distant. Marianne Payot

By Omar Youssef Souleimane.

Flammarion, 156 p., €19.

A vibrant declaration of love to a host country

© / Editions Flammarion

When he arrived in France in 2012, fleeing the bloodthirsty regime of Bashar al-Assad against which he had dared to revolt, the young Omar Youssef Souleimane only knew one word of French, borrowed from his favorite poet Paul Eluard: ” freedom”. Six years later, he published his first book in his adopted language, The Little Terrorist. “Despite many mistakes and my notable accent, I discovered a new voice within myself when speaking French, different from the one with which I speak Arabic. It is stronger, freer. Little by little, I identified with this voice. I was forging my own language, that of an exile who was building his integration through words. Being French is, for the refugee that I am, above all being bound by language,” he explains magnificently. .

Being French is a vibrant declaration of love to a host country which saved him from tyranny and offered him freedom, “a gift of which only those who have lived in a dictatorship know the value”. But Omar Youssef Souleimane also describes the melancholy heartbreaks of exile, and the impossibility for him to see his native country, Syria, and more particularly his mother again. Failing that, he lovingly defends his surrogate “mother”, France, worrying about Islamist separatism as well as the growing disinterest of young people in democracy. In 2021, after obtaining French nationality, the writer sent euphoric text messages to everyone he knew. Due to Covid-19, the identity card ceremony was canceled. But Omar Youssef Souleimane organized his own ceremony with his friends, going to eat couscous (“the favorite dish of the French”), toasting red wine and listening to Rachid Taha and Barbara. “This is the France that I love,” he concludes. Thomas Mahler

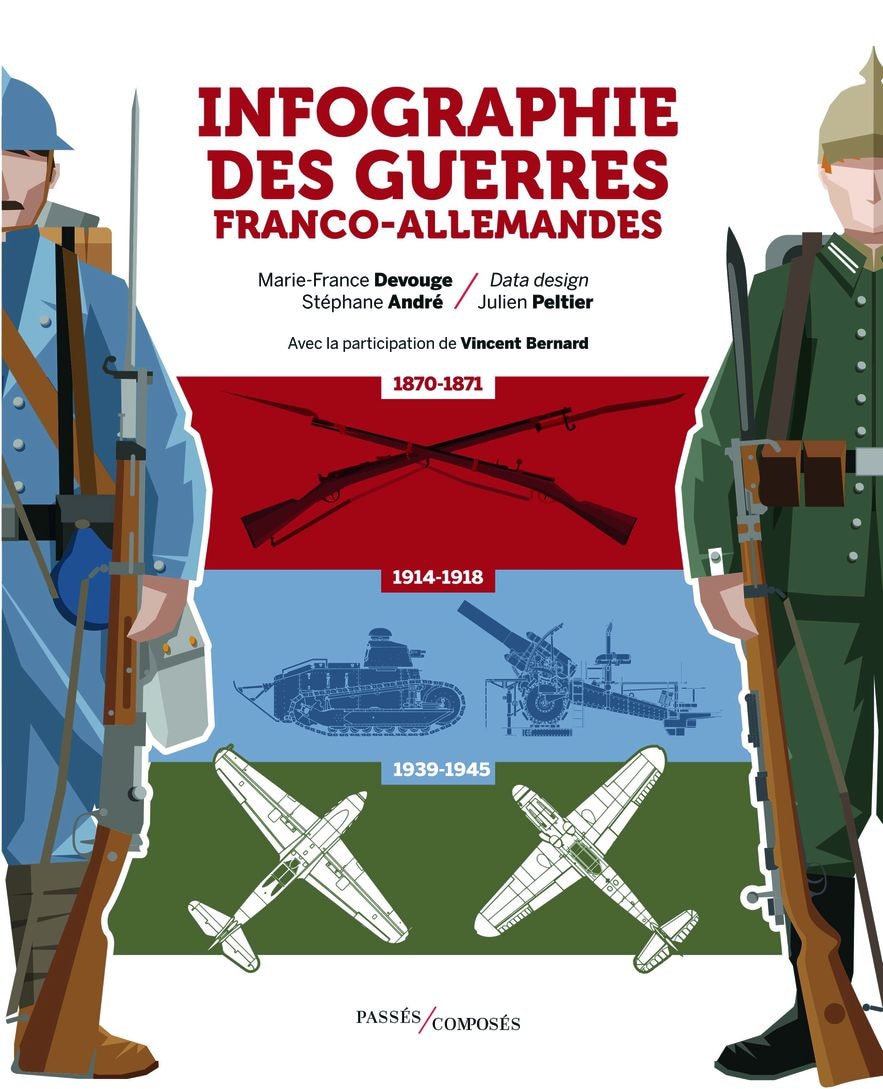

Infographics of the Franco-German Wars

By Marie-France Devouge, Stéphane André and Julie Peltier (data designer) with the participation of Vincent Bernard.

Past, composed, 171 p., €29.

To understand everything about the three conflicts that saw the French and Germans clash

© / Past/Composed Editions

Three wars. Two countries. A battlefield. By bringing together in a single work the three Franco-German conflicts (1870-1971, 1914-1918, 1939-1945), the Passés Composés editions had a rich idea as it is true that the first – the most unknown – deserves its place alongside the other two with which it forms a continuum of massacres. A tragic picture, this triptych is all the more fascinating because the original form of the work – infographics – allows comparisons and perspectives. “This new way of telling history broadens our audience to non-history enthusiasts and to a younger readership,” rejoices the publisher. The formula is winning: Ancient Rome infographic, a previous installment in the series, reached 200,000 copies worldwide. And Infographic of the Napoleonic Empirepublished almost at the same time asInfographics of the Franco-German Wars, should also be a hit at Christmas. Because of its educational power, the latter deserves the same attention.

You enter through double pages illustrated with maps, drawings, comparative tables and statistical data. At a glance, we understand the extent of the humiliation of the war of 1870: 151,000 French deaths and 384,000 prisoners, compared to three times and forty times fewer respectively on the German side! We measure the change in life expectancy at the start of each war: 36 years in 1870, 51 years in 1914, 52 years in 1939. We see the armament of each army, their chains of command; the production of each country, the colonial expansion of the belligerents, the organization of the trenches, the progress of military maneuvers (Sedan in 1870, the German offensive in 1940, etc.). Everything seems simple and clear. We understand each infographic thanks, also, to clear texts. Incidentally, we understand that the Ardennes, crossed by the three conflicts and present in each chapter, were also “lands of blood”, as they say of Ukraine, whose current conflict closely resembles our Franco-German “butcheries”. Axel Gylden

Allary Editions, 219 p., €18.90.

The slight slump of a man who would like to have the right to a second chance.

© / Allary Editions

What are we going to do with him? The narrator of Everything that’s missing is an already old-fashioned 40-year-old writer, who could resemble a mix between Olivier Adam and Nicolas Rey. One day, his partner Ana gets tired of him and kicks him out like someone taking out the trash. Our man goes to Austerlitz station to take a train to the Dordogne and his family home. Will he find rest there? Nothing is less certain… There, between two walks with his dog, the jilted novelist sees only one way to get back on track: write a well-crafted book that will redeem him in Ana’s eyes. This is not an easy task. In the author’s residence genre, the attic of his parents’ house has little to do with the Villa Medici. Despite the discomfort, he moves forward with his manuscript. But the memories of fifteen years of living together disturb him.

Happy and unhappy moments, funny anecdotes, the flashes follow one another – the funniest has to do with Iggy Pop, but we won’t say more about that here. In a tone that is both bitter and amused like John Fante, Florent Oiseau recounts the slight slump of a man who would like to have the right to a second chance. Bird’s first novel was called I’m going to get started. No procrastination here: in a few weeks, his antihero will have completed his text. Will Ana forgive him? Some actresses over 40 complain that they are offered fewer roles. They would know by reading Oiseau that writers of the same age are doing even worse – but with a smile.

Louis-Henri de La Rochefoucauld

Plea for the dream, first book by Samuel Dufay

© / Editions Grasset

What a strange young man is Samuel Dufay who, from the first page of his short story, cites Bernanos and Modiano before moving on to Miossec and Dostoyevsky. A young man of 28, vaguely disenchanted but capable of the greatest excitements, such as in football, The Team, his Bible, and all these papers that we find in the last kiosks open. A young man also in love with Paris, with his beloved 12th arrondissement, and with Nestor Burma, whose ghost he sees everywhere, from the Place de la Nation to that of Victoires, and whom he has chosen as a guide for his nostalgic wanderings of a past _ France before digital technology _ that he barely knew.

And then, very quickly, Samuel Dufay comes to the point, to his parents, to his father, above all, a normalien from Montmartre, a graduate of letters, a long-time journalist at Point before joining L’Express and being hit by a driver on a mountain road one day in February 2009, at the age of 46. Inconsolable, Samuel, who “grew up leaning over a grave”, reads and rereads the articles of his father, François, the journalist with the salt and pepper puff and author of some noted books (The Autumn Journey, Sulfur and musty). This father who told him about Gaulle and François I to put him to sleep at night. Completed with letters in his turn, “the son of François” ended up following in the footsteps of his father and his grandmother, after a detour through National Education. Today he delivers his fine paper shroud to his dearly departed with a beautiful and gentle gravity. MP

.