The Scepter and the Feather

From Montaigne to François Mitterrand, by Bruno de Cessole

© / Editions Perrin

This is a French exception: for centuries, literature and politics have been linked. In The Scepter and the Feather, Bruno de Cessole paints with erudition and style the portrait of around twenty great national figures who, from Montaigne to François Mitterrand, knew how to play on both fields. From Napoleon, in whom Cessole sees a writer of the caliber of Stendhal, to Saint-Simon, Chateaubriand, Hugo or Malraux, who would have liked to play a major role in the destiny of our country, the evolution of these men goes in one way or the other: from politics to literature, or from literature to politics.

Cessole remembers a key date: 1643. It was then that Richelieu created the French Academy. The authors, who until then had only been subordinates, servants in the service of the Great, then rose to prominence and formed a political body. In the 18th century they emancipated themselves, going so far as to form the most influential party in France, according to Tocqueville. The 19th century did not calm their megalomania. The 20th marked a gradual decline: after de Gaulle, a true writer, communication gradually took over. If Cessole has esteem for Pompidou and Mitterrand, he is more circumspect with regard to the novels of Valéry Giscard d’Estaing – which herald those of Bruno Le Maire. Readers of Sainte-Beuve and Albert Thibaudet are advised to read this masterful essay in literary criticism: if current politicians are no longer interested in literature, Cessole proves that certain writers still have a vision of our history. Louis-Henri de La Rochefoucauld

Love

By François Bégaudeau.

Verticals, 96 p., €14.50.

A short and beautiful novel by François Bégaudeau

© / Gallimard

Love or rather love, with a small a, as indicated on the cover of the 17th book by the “revolutionary” critic, director and writer François Bégaudeau. With or without capital letters, we delight in reading this short fiction which immerses us in the banality of a long marriage with words of unparalleled accuracy. No crisis, no salient or miscellaneous event, no majestic flight or glorious destiny, but life flowing, with its tenderness and its quibbles, its attentions and its petty reproaches. And that we would like to never see end.

We are in the Pays de Loire, at the beginning of the 1970s. He, Jacques Moreau, works in his father’s masonry company, she, Jeanne, a receptionist in a hotel, drools over Pietro, a charming and fickle basketball player… It’s the era of the Simca 1000 and the 3 CV, the La Redoute diaries, the pig festival, Europe 1 and family bingo. Jacques spots her, but he is clumsy, entangled. However, the matter is done. One Easter Sunday, Jeanne is invited to the Moreaus. Jacques is hired as a municipal gardener, and Jeanne as a secretary at an insurer. Marriage, birth of Daniel, birthdays follow one another, Jeanne is crazy about Richard Cocciante, “the ugly rital” in the eyes of her husband, who is passionate about building rocket models. The years tick by, the little quibbles multiply. Nothing serious, “love will never pass”. Marianne Payot

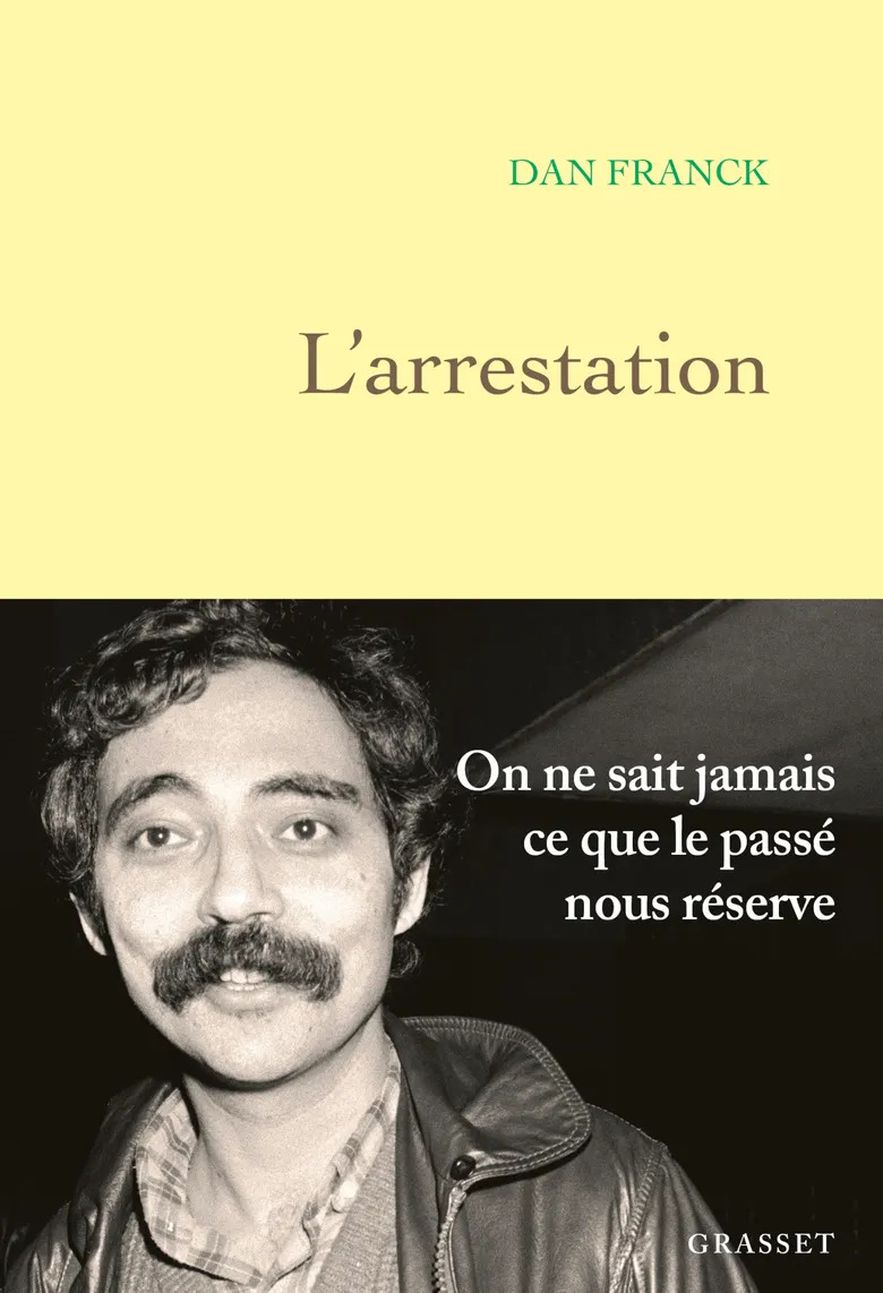

The Arrest

Grasset, 360 p., €21.90.

When Dan Franck was incarcerated at the Santé prison…

© / Editions Grasset

Dan Franck never spoke about it, his own daughter ignored it, until in 2016 his Wikipedia entry exposed him and in doing so cornered him. Four lines therefore which recall that in 1987, during a trial on the Direct Action movement, he was sentenced to eighteen months in prison, suspended. Thirty books written since then, around twenty films for which he wrote the screenplays, two illustrated albums, four decades of dense life and yet nothing was erased, forgotten: this time he had to tell this story, deliver his version. He, in love, a thirty-year-old with a very left-wing heart, flitting around with his group of literate friends, who sublets his studio to a friend, whose mythomania he admires and hates the Weston shoe collection. He is unaware that the latter, an old acquaintance from the Rueil-Malmaison high school, is having the telephone exchange and the rear base of Action Directe installed there.

1984, Dan Franck is denounced by an anonymous letter, monitored and listened to by the police, questioned by judge Bruguière, then, during the last major trial of Direct Action, condemned for “criminal conspiracy” and incarcerated in the prison of the Health, where only his father has permission to visit him during the forty days he spends there, twenty of which are in solitary confinement. The Arrest captive, hypnotic dissection of a casual and fierce friendship, especially since the young man lies during the investigation – the passage devoted to his interrogation by the judge from whom he persists in hiding the truth, is dizzying. A dry, thrilling story. Emilie Lanez

There are still people passing by in the street.

“There are still people passing by in the street”, an enigmatic title for a work of vibrant wanderings

© / POL Editions

From writing to writing, Robert Bober continues his wanderings. As he notes in his introduction, repeating a phrase from Aragon, “this book will undoubtedly resemble nothing but its own disorder.” To our delight ! What is also fascinating here is the age and vivacity of its author: 92 years old! Yes, Robert Bober, born in Berlin to Jewish parents of Polish origin who emigrated to France in 1931, is well and truly over 90 years old. However, the director (more than a hundred documentary films to his credit), came to late to writing with What’s new about the war? (1993) then Berg and Beck (1999), has lost nothing of his memory and his ability to delicately bring to light, from one chapter to another, memories “sometimes painful, sometimes soothing”. He chose his first reader, Pierre Dumayet, his friend and accomplice, with whom he created so many portraits of writers, who died in 2011, to whom he addresses here to tell him about today and yesterday.

He talks to him about Saul Steinberg, Harpo Marx (present in his first documentary, Cholem Aleikhem, a Yiddish-language writer), and whose reading of the very beautiful Harpo (Actes Sud) by Fabio Viscogliosi revives the figure; by Georges Perec, of course, by Marcel Cohen, by Robert Doisneau, by Yasmina Reza and by her dear Elen, who died in December 2021 (“It was in July 1949, at summer camp, that we exchanged our first kiss” ). He returns precisely to these famous holiday camps, and in particular to those organized in a castle in Draveil by the Union of Jews for Resistance and Mutual Aid in the aftermath of the war where he met little Zozo, who escaped at the age of 11 from Vel d’Hiv. With Robert Bober, we also revisit the rue de la Butte-aux-Cailles, when his parents’ shop, located at 30, proudly displayed “Manufacturing rods”, while at 7 of the same street, his class friend and son of grocers Henri Beck was deported and gassed in August 1942 with his entire family – a commemorative plaque was installed in January 2022. From one childhood to another… on the walls of the neighborhood, you can discover the marvelous drawings by Seth that Bober reproduces in his work: a little girl playing hopscotch, another carrying the Ukrainian flag, etc. Bober investigates, and meets the author of these urban paintings, Julien Malland in civilian life, who, in 2017, went to paint a school in Pospana, in Donbass, then on the front line. These are certainly the most moving pages of these delicious Boberian wanderings. MP

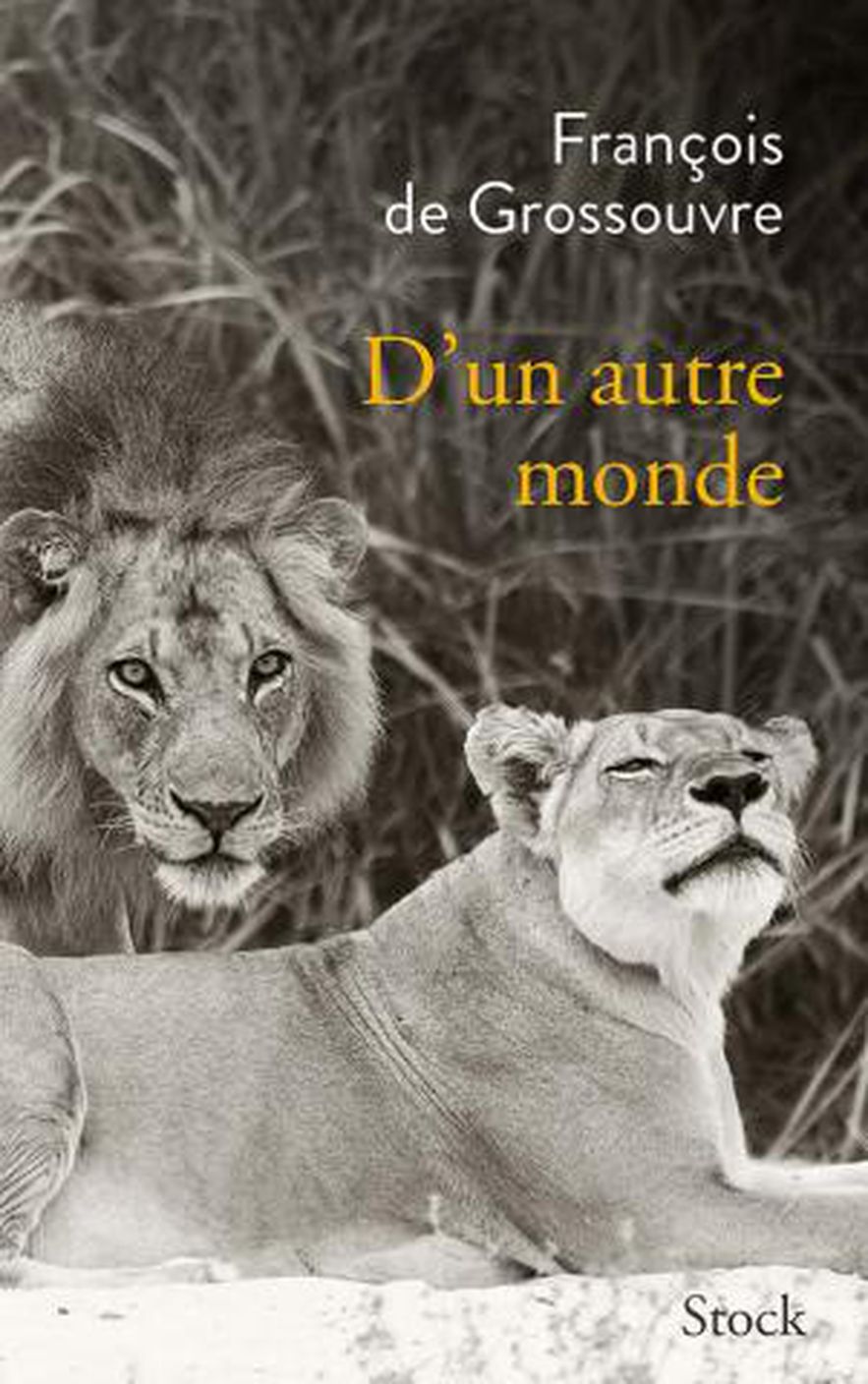

From another world

By François de Grossouvre.

Editions Stock, 252 p., €19.90.

The first book by the grandson of the late former advisor to François Mitterrand

© / Stock Editions

They enter the room, each of the grandchildren invited to choose from among the deceased’s objects the one they wish to keep as a souvenir. April 1994, François de Grossouvre is 18 years old, he has the same first name and the same surname as his paternal grandfather, this close advisor to François Mitterrand who was found “dead from a 357 Magnum bullet in his office at the ‘Elysium”. The grandson disdains his beautiful watches, he makes his own a bracelet brought from Africa, made of elephant hair, the one worn by his grandfather who was crazy about hunting. A few days later, leaving behind his baccalaureate exams, he flew to Africa. He stayed there for fifteen years. Tanzania, Central African Republic and Cameroon, where a hunting guide on foot, he learns to follow the lion to the sound of his Kudu horn, to track down the leopard from which his client dreams of making a coat, to fight against killers who trade monkey hands.

This book is his first, ten years spent writing it. How can we convince people that these safaris are the only way, according to him, to preserve wild life reserves threatened by the rapacity of poachers? And then, he said, his voice tight, to write to rehabilitate his grandfather, the one whose stiff silence and loving knowledge of the forest he admired as a little boy, the one whose death shattered his youth. A few harsh pages to recall the botched investigation and the validated suicide thesis; he doesn’t believe it, “nothing holds”. In the tall straw of the savannah, he forgot Paris, its secrets and its nightmares, he learned that wild animals only kill out of necessity. He now lives in Patagonia. EL

.