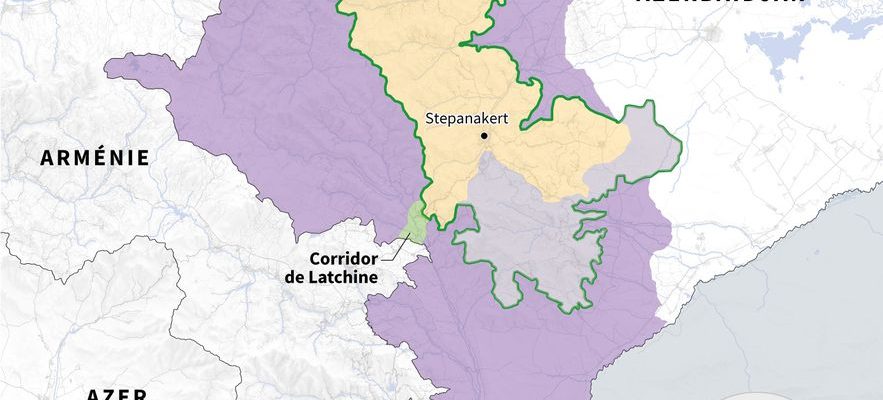

For several months, the Lachin corridor has concentrated most of the tensions in the Caucasus region. Lost in a winding landscape, this road, 65 kilometers long and bordered by mountains, is the only axis of communication linking Armenia to the independence territory of Nagorno-Karabakh. An Azeri separatist enclave populated mainly by Christian Armenians, and which depends largely on external supplies.

However, since the end of 2022, Baku has continued to multiply the pretexts to obstruct traffic on this vital artery, even if it means triggering a new escalation in the conflict which has opposed the two former Soviet republics for 30 years. A military offensive was notably launched in Nagorno-Karabakh on Tuesday. Expected for several weeks, this attack by the Azeri army ended after 24 hours of deadly fighting with a ceasefire agreement on Wednesday. Despite the desire displayed by Azerbaijan for a “peaceful reintegration” of Nagorno-Karabakh and the organization of talks this Thursday, September 21 in the Azerbaijani town of Yevlakh, the blockade imposed by the Azeris over the last eight months raises fears of a deterioration of the humanitarian situation in the region.

An unprecedented humanitarian crisis

Shortage of food, medicine, gasoline, and sometimes even water and electricity. Food is rationed, and access to medical and hospital care has become impossible due to the blockade imposed by Azerbaijan. “Our only road to the outside is closed. We have no electricity, it is supplied in timed slots,” explained Liana Ataïan, a resident of Nagorno-Karabakh to our AFP colleagues last June. “Our children, the elderly and pregnant women have no fruit or vegetables to eat,” adds this 47-year-old woman.

An untenable situation, which however seemed to improve in mid-September, when Baku declared itself ready to authorize the “regular” passage of humanitarian aid from the Red Cross. Monday September 18, 24 hours before the Azeri army’s offensive, humanitarian convoys were able to take the road leading to the separatist enclave. Foodstuffs and medicines were therefore transported. Enough to reassure the international community, which was worried about the humanitarian situation there, where the 120,000 inhabitants of Nagorno-Karabakh have been rationed for more than eight months now.

“Hindered” traffic from December 2022

While an easing of tensions seems to be taking shape as the end-of-year holidays approach, the UN Security Council is alarmed by the situation in the Lachin corridor. On the 12th of the month, Azeri demonstrators who claim to be environmental activists blocked access to the road near Shushi, a town of 4,000 inhabitants located in the heart of Karabakh, around forty kilometers from the Armenian border. Without expanding further, Azerbaijan assures that it is a question of groups of demonstrators who came to protest against the installation of illegal mines. But for Yerevan, no room is left for doubt. This is indeed a maneuver knowingly orchestrated by the Azeri government with the sole aim of isolating the population of Nagorno-Karabakh in a “medieval siege”, under the backdrop of “ethnic cleansing”.

Nagorno Karabakh

© / afp.com/Valentin RAKOVSKY, Sophie RAMIS, Laurence SAUBADU

Initially, Baku is sticking to its initial position, insisting that no blockade is in progress, and ensuring that transport and deliveries of vital products have not been affected in any way. But in April, Azeri forces justified the installation of a military checkpoint on the Hakiri bridge – which provides the junction between Armenia and the Lachin corridor – for security reasons. Azerbaijan once again assures that the security point in no way prevents humanitarian convoys from traveling along the Lachin corridor. This is firmly contested by the Armenian Prime Minister, Nikol Pashinyan, who has since continued to warn of the “extremely deteriorated humanitarian situation” in the separatist enclave.

“Temporary” suspension of traffic

But while the noose tightens around the inhabitants of Nagorno Karabakh, cut off from the rest of the world for more than six months, and despite the decision of the International Court of Justice rendered last February, Baku announced on July 11 the “temporary suspension “of traffic in the corridor. Once again, Azerbaijan is playing a cautious role, asserting that the Armenian branch of the Red Cross is engaging in “multiple smuggling attempts”. In the process, border guards declared having seized between July 1 and 5 around ten cell phones and hundreds of packets of cigarettes during searches in these vehicles. Although denied by the Red Cross, the accusations were enough to bring down the curtain at the Lachin border post.

At the Quai d’Orsay, there are fears of a further escalation of tensions. “We are seriously concerned by the announcement made by Azerbaijan,” declared the spokesperson for the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Anne-Claire Legendre the day after the establishment of the blockade. On August 15, a month after the holding of talks between Armenia and Azerbaijan in Brussels, the head of diplomacy Catherine Colonna deplored a “persistent blockage by Azerbaijan, which contravenes the commitments made within the framework of the agreements ceasefire and harms the negotiation process. On the Elysée side, Head of State Emmanuel Macron promises “a diplomatic initiative” in order to increase pressure on Azerbaijan.

The timid EU and an ally that embarrasses France

But despite the numerous warnings from the Armenian Prime Minister, who declared at the end of July that a (new) war (with Azerbaijan) is very likely, France and the European Union appear somewhat undecided as to the posture to adopt. Although Baku is responsible for an unprecedented humanitarian crisis, the European Union has not yet taken any sanctions against Azerbaijan. A position at first glance surprising, but which may in part be This can be explained by the fact that this country of 10 million inhabitants has been, since July 2022, one of the main gas suppliers to the Twenty-Seven.

Moreover, since the start of the conflict, Moscow has been one of Armenia’s main supporters. Enough to embarrass France, engaged in the process of sanctions taken against Russia following the Ukrainian invasion. But while Russian peacekeeping soldiers were deployed in the region at the time of the signing of the ceasefire at the end of 2020, Nikol Pashinyan criticizes his ally for failing in his mission. According to the Armenian Prime Minister, either Russia “is incapable of maintaining control over the Lachin corridor”, or it “does not have the will”.

Nikol Pashinyan

The day after the blockade, a Nagorno Karabakh official urged Russia to restore traffic on the corridor. “I appeal to the Russian Federation […] so that it guarantees the free movement of people and goods on the corridor,” Minister of State Gurgen Nersisyan declared on social networks, assuring that “the situation is terrible, and will have irreversible consequences in a few days.” To this request, the Russian Federation is content to respond with calls from Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov, “to lift the blockade”. Insufficient to ensure a complete and definitive re-opening of the corridor. As well as to avoid an offensive army.