The term “Rhythm’n’Blues” is as used as it is indefinite. Behind this imprecise name hide a multitude of artists and musical currents that shaped the Afro-American landscape of the second half of the 20th century. Belkacem Méziane is the author of a didactic work bringing together a hundred representative titles of this form of expression which drew the contours of L’Épopée des Musiques Noires.

“Jump Blues”, “Doo Wop”, “Boogie-Woogie”, all these obscure terms are all necessary ingredients for the genesis of “Rhythm’n’Blues”. Admittedly, this does not give us many more keys to understanding, but it is necessary to tame these idioms in order to become aware of the musical revolution that shook the United States at the turn of the 1950s. For many musicologists, the “rhythm” n’Blues” is the matrix of Rock’n’Roll. This assertion, however, is incomplete and reductive. The African-American social history must imperatively be taken into account to apprehend its cultural value.

Before the “King” took over the repertoire of his contemporaries, the matrix of his inspiration was already quivering in the voices, instruments and compositions of black musicians from the southern United States. Segregation had only and sadly muzzled these distinguished artists unable to make their talent heard on a national scale. Who remembers Arthur Big Boy Crudup or Big Mama Thornton? They are, however, the first to have performed works immortalized by Elvis Presley. We weren’t yet talking about “Rock’n’Roll” at that time even if the fervor and the harmonic structure strongly resembled this musicality that was soon to sweep the world.

The “Rhythm’n’Blues” was therefore the sediment of our current soundscape. Already in the 1940s, the vibraphonist Lionel Hampton imposed on his orchestra an astonishing vigor supported by a few renowned blowers, including the saxophonist Illinois Jacquet who electrified the title flying home through a fiery solo that has become legendary. We were in 1942 at the dawn of a major artistic transformation. Racial discrimination was unfortunately the main obstacle to the effervescence of “Rhythm’n’Blues”. Yet many of them carried the torch and claimed an identity rooted in the black soul. Hal Singer, Big Jay McNeely, Louis Jordan, and so many others have written great chapters in this hoped-for ecumenical adventure.

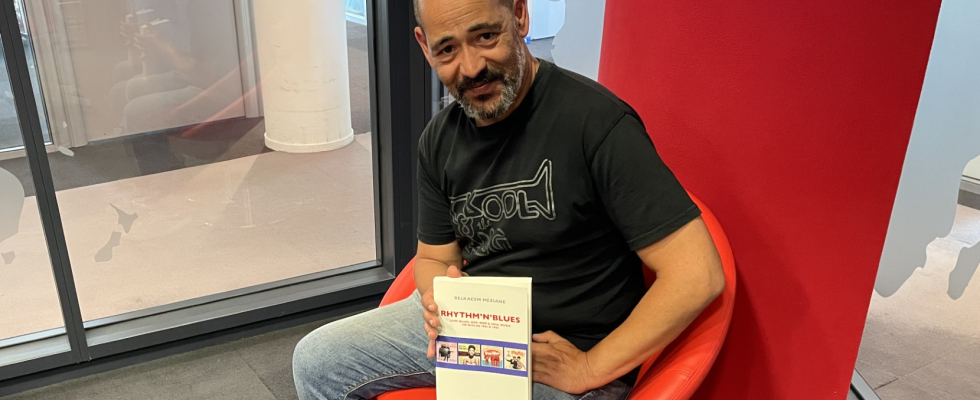

The almost simultaneous birth of “Soul-Music” and “Rock’n’Roll” precipitated the disappearance of the term “Rhythm’n’Blues”, but its spirit resisted the erosion of time. Aren’t we talking about “R&B” today? This long journey has embraced the destiny of Black Americans for 80 years. In his book, Belkacem Meziane was able to choose the 100 representative titles of this prodigious Epic.

To read : Rhythm’n’Blues – Jump Blues, Doo Wop, Soul-Music – 100 hits from 1942 to 1965 (Editions The Word and The Rest).