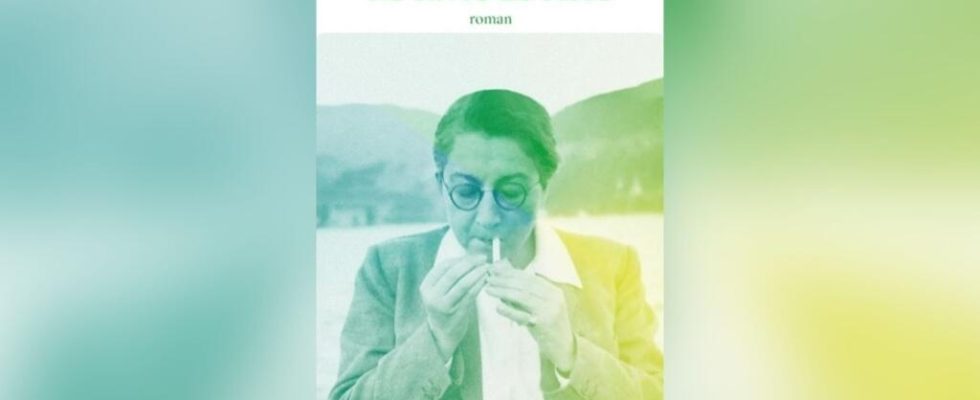

The author Emmanuelle Favier publishes in this literary season a novel dedicated to the resistance fighter and museum curator, Rose Valland, who played a decisive role in the protection of French artistic heritage during the Second World War. Rose’s book pays homage to him and raises essential questions such as that of transmission in our current societies.

RFI: You sign for Les Périgrines editions Rose’s book, it is a story novel around the character of Rose Valland, a figure of the resistance who has long been forgotten and who for a few years has been brought back to light. How do you explain this renewed interest around Rose Valland ?

Emmanuel Favier : I think there is a contemporary movement to rediscover and rehabilitate figures of women and in particular figures of resistance fighters. She’s a very interesting character, in my opinion, because she transgresses all determinisms. That is to say that she will transgress gender determinism, as a resistant woman and in a male environment that are the circles of art historians and heritage protection.

She had a rather unique place. As a woman from a modest background, she transgresses social determinism. In 1939, when war broke out, she was attached to conservation at the Jeu de Paume museum in Paris, that is to say, she was a volunteer. This means that she is rarely and with difficulty paid for her action, and this is one of the aspects of the sexist discrimination to which she is subjected.

Rose Valland will show incredible courage during the war by protecting French heritage with the Director of National Museums, Jacques Jaujard. Their role is fundamental, because without them and without Rose Valland, everything the Nazis despoiled could have been lost forever.

This is where Rose comes in, since the works that were looted by the Nazis from galleries, apartments, from Jewish collectors were first stored in the Louvre and very quickly then in the Jeu de Paume museum. Rose will note very precisely the origin of the works and especially their destination. It will identify a number of deposits in Germany.

It is thanks to these clandestine notes that she took at the risk of her life – she was very closely watched and moreover the Nazis had made it clear to her that as soon as they no longer needed her, they would take her. would run – that she stayed. She noted everything down and passed the information on to Jacques Jaujard. Thanks to her, about sixty thousand works were found after the war. It is estimated that more than a hundred thousand, and probably even more, the number of looted works.

Also to listenGrand Reportage – Tracking down works looted from Jews by the Nazis

It’s not a biography that you sign, but a story that features a young director who is thinking about making a documentary on Rose Valland, and your character asks essential questions, such as that of transmission. Is this question at the heart of the story ?

Yes, that’s really the main angle of attack. The thing that struck me was this idea that the transmission for her took on a collective dimension, and not at all individual, which is not very feminine, by the way. So that is very important to me, and this device where I staged a documentary filmmaker allowed me to resonate Rose’s questions on a collective and historical level, with the more individual questions that correspond to our own societal questions today. That is to say that it is no longer just a matter of protecting artistic heritage, but it is a matter of positioning women in particular in our society, in their relationship to memory.

The fact of producing a work and being an artist puts things a little differently. It is true that it is often said that our works are our children. This is also where we will inscribe something of our vision of the world. When you raise a child, there is also something like that. I transmit a vision of the world, I transmit values. That’s exactly what you do as an artist.