The expression has now entered common parlance. The media use it all the time and the general public knows its meaning. Few people remember, however, the event at the origin of the discovery of Stockholm syndrome, which is celebrating its 50th anniversary.

On August 23, 1973, in the middle of summer, Jan-Erik Olsson burst into the Kreditbanken branch in the Norrmalmstorg district of Stockholm. This prisoner on the run for several weeks does not suspect for a moment that what he is about to do will bring to light a psychological mechanism never before documented.

Once inside the bank, he fires a burst of machine gun fire into the ceiling, lets most of the employees get away, but takes three women and one man hostage. He threatens to kill them as dozens of police now surround the building. Immediately, the Swedish police, renowned for their moderation, negotiated to avoid any recourse to violence. Jan-Erik Olsson then claims three million crowns (300,000 euros), a car and a plane ready to take off from the airport. More surprisingly, he demands that an inmate named Clark Olofsson be released from his cell so that he can join him. The two men know each other, they were fellow prisoners. The government cooperates and agrees to release Olafsson who joins Olsson and the hostages in the bank during the day. Then begins a soap opera that will keep all of Sweden in suspense for five days.

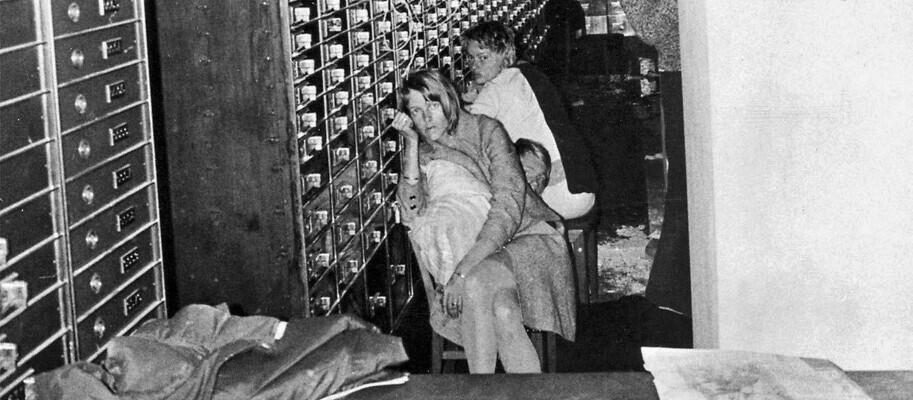

To avoid being within firing range of the snipers, the two robbers and their hostages will then take refuge in the vault of the bank, in the basement of the building. Lengthy telephone negotiations ensued. The day after the start of the hostage-taking, on August 24, the chief of police, commissioner Lindroth, obtained permission from the robbers to come down and see that the hostages were in good health. To his surprise, he realizes that the four hostages show him a certain hostility, the policeman even finds them relaxed and friendly towards their captors.

” Believe it or not I had a great time with them »

Subsequently, journalists manage to obtain the bank’s telephone number and manage to speak with the hostages. Once again, their remarks greatly astonished the press. ” I’m not afraid of Olsson and the other guy at all, I’m afraid of the police. If we go with them, there’s a chance they’ll kill us, but they won’t do that, one of the hostages tells them. I don’t think they will do that. I trust them completely, I will go around the world with them without hesitation. Believe it or not, I had a great time with them, we chatted and all that. The only thing we fear is a police attack, we are scared to death “.

Telephone negotiations will continue without success. One of the hostages, Kristian Enmark then aged 22, then decided to call the Swedish Prime Minister at the time. She then explains to Olof Palme that she is afraid ” that the police storm and put their lives in danger “. She begs him to do everything to let them out of the bank with the robbers and let them escape. Faced with the Prime Minister’s categorical refusal, the young woman said to herself ” very disapointed “. ” I feel like we’re juggling our lives. I have complete confidence in Clark and Olsson, I’m not desperate. They did us no harm, on the contrary, they were very nice “, declares the young woman to a taken aback Olof Palme.

In just a few hours, the hostages seem to have established a great relationship of trust with their captors. Conversely, they show great distrust of the police. It must be said that as soon as the police try a new approach, it contributes to making the situation a little more tense each time. The police will for example take the side of locking up the robbers and their hostages, without their consent, in the safe room. They will also promise the four hostages that they will be able to contact their family by telephone when the line had been voluntarily cut by the police. All of this will only further fuel the group’s mistrust of the police.

Hostages refuse to come out

After five days behind closed doors, the police will finally find a way to force the group out of the vault. The police decide to drill holes in the ceiling of the room and send tear gas. Cornered, the hostage takers end up agreeing to surrender. But when the police open the vault door, to everyone’s surprise, the hostages refuse to come out. They fear that upon leaving the room, Olsson and Olafsson will be shot. They therefore ask that the two men come out first, which the police eventually agree to. Before leaving, the two robbers and four hostages say goodbye by hugging each other, under the dumbfounded eyes of the police officers present on the spot.

The sympathy of the hostages for their captors will not stop there. Jan-Erik Olsson will be sentenced to 10 years in prison for this hostage taking. Clark Olafsson will be acquitted, but will still have to serve the end of his sentence. During the trial, all the hostages refused to testify against the two men, for several years they will also visit them in prison.

The psychiatrist Nils Bejerot, who was part of the team of negotiators deployed by the Swedish police, was the first to report the strange behavior of the hostages which he first named the Norrmalmstorg Syndrome. It was not until 1978 that American psychiatrist Frank Ochberg, who defined the syndrome for the FBI, definitively named it Stockholm syndrome. He then describes it as an empathetic manifestation of the victims towards their aggressor. This is then akin to a self-defense mechanism of the victims who choose to adopt the point of view of their abductor, thus hoping to maximize their chances of survival. ” When a normal person is kidnapped by a criminal who has the power to kill him, within hours the hostage has a kind of regression to infantile emotions: he can’t eat, talk, go to the bathroom without permission. Doing so is a risk, so she accepts that her captor is the one who gives her life, as her mother did. », explains Frank Ochberg,

A mechanism at work in other cases

Other cases will come later to illustrate this psychological mechanism. The most significant is probably that of the kidnapping of Patricia Hearst in California in 1974, barely six months after the Stockholm robbery. The 20-year-old, heir to the Hearst Corporation media group founded by her grandfather William Hearst, is kidnapped from her home by a terrorist group claiming to be the Symbionese Liberation Army. Several weeks later, the police track her down when she participates in a bank robbery with her captors and refuses to surrender.

In 2006, Austrian Natasha Kampusch manages to escape her captor Wolfgang Priklopil who had been holding her since 1998 after kidnapping her at the age of ten. The man committed suicide, which particularly affected the young girl. Many Austrian media then speculated that she might have Stockholm syndrome, which she has always denied.

The syndrome described by Nils Bejerot and Frank Ochberg shares similarities with many psychological mechanisms such as identification with the aggressor, a concept theorized by Anna Freud in 1940. Stockholm syndrome also shares many similarities with psychological mechanisms work with abused children or victims of domestic violence.

If the syndrome has entered popular culture, it is now very rare to observe cases of hostages struck by Stockholm syndrome. For this to happen, three criteria are necessary: the kidnappers must be able to act with the victims, there must be no ethnic antagonism or feeling of hatred of the kidnappers towards the hostages and above all, the hostages must not have previously knowledge of the existence of the syndrome. The phenomenon is now so well known that it could well be a victim of its celebrity.