What would L’Express be without its illustrious founders, famous columnists, famous journalists? In 2023, our newspaper celebrates its 70th anniversary, an ideal opportunity to pay tribute to the characters who gave this weekly a raison d’être, an editorial line. At the origins, a mythical couple, Françoise Giroud and Jean-Jacques Servan-Schreiber, who inaugurated on May 16, 1953, the first issue of the weekly, driven by “an anger”, as Giroud will tell, the anger to see France according to them so badly governed. Aided by senior civil servant Simon Nora, who will notably take charge of the Economy pages, the duo is leading the charge against economic and diplomatic policy, and politics in general, led by the government. Over the years, they will be joined by high quality writers, some of whom have agreed to tell us about their time spent writing alongside these unforgettable bosses.

From 1953, L’Express welcomes a committed writer, François Mauriac, then, from 1955 to 1956, his best enemy Albert Camus. Nearly twenty years later, the philosopher Raymond Aron joined the editorial staff, attracted by the ultra-liberal thought of the boss at the time Jimmy Goldsmith, shortly before Jean-François Revel, an associate professor of philosophy like Aron, took over the management of the newspaper. Giroud, Servan-Schreiber, Nora, Mauriac, Camus, Goldsmith, Aron, Revel: eight outstanding personalities to whom L’Express owes so much and whose story and life within the editorial staff we wanted to tell, so that readers can understand our world of yesterday so precious for understanding that of tomorrow.

EPISODE 1 – Catherine Nay: “For Françoise Giroud, any woman who arrived at L’Express was a rival”

EPISODE 2 – Jean-Jacques Servan-Schreiber, the founder: “And if we created a newspaper?”

EPISODE 3 – Simon Nora, “the economist of L’Express who wanted to stem the populist surges

EPISODE 4 – Albert Camus at L’Express: the passion of commitment

© / The Express

For its 70th anniversary, L’Express has decided to honor all those who contributed to writing the most beautiful pages of its history. While in the mid-1950s, the institutions of the Fourth Republic struggled to raise France to its rank, watching it sink into colonial wars with morally disastrous consequences, a young guard of journalists engaged in the battles of their time. : his audacity could make you dizzy. Françoise Giroud and Jean-Jacques Servan Schreiber formed its intrepid vanguard. This infernal couple – to hear the most conservative – had gathered around them the sharpest feathers in Paris, whom nothing exhausted or stopped. Some were there, already crowned with their experience in the press and its agencies, like Pierre Viansson-Ponté. Many had a political commitment, like Léone Georges-Picot who worked alongside Pierre Mendès France, while the majority shared the feeling of contributing to a collective work of political and moral recovery. This was the case with Georges Boris, also in the wake of Mendès France and former editor of the radical-socialist weekly The light, founded in 1927, but also Jean Daniel, Alfred Sauvy and Maurice Merleau-Ponty. One could hardly dream of a more singular and prestigious writing at the same time.

It is true that in her first editorial, Françoise Giroud set the tone, setting the bar very high. “The man who will read us does not yet exist, but we know him well, he says to himself: If they have courage, they will not have readers and if they want to have readers, they will not be able to have courage. The man who will read us is not pessimistic, he is a little discouraged because he feels alone…”

“François Mauriac and Albert Camus wrote their articles and sent them into the atmosphere of the heights where they stood, with an analytical acumen that made them respected by all.”

Doubtless Françoise Giroud and Jean-Jacques Servan Schreiber already had the intuition that in times of great upheaval, the most gregarious minds would seek to blend in with the crowd, yielding to the spirit of the times: the fear of eing alone and left to their own fate often led the weakest to quickly depart from their free will. On the other hand, those who took the risk of resisting could be mocked and abandoned to their melancholy, so much so that loneliness became for them an asceticism, which only the passion for the truth managed to make bearable. In such circumstances, courage measured the propensity of each to accept his thankless condition. And in order not to have to renounce their convictions, some consoled themselves for many torments when the vociferous packs formed, drowning all reasoning with their din. The being enamored of truth and desirous of always remaining in motion had first to arm himself with patience and to fight. It is in this way that certain minds were distinguished from the mass, whose ethical requirements placed them above them.

From 1954, within the editorial staff of L’Express, François Mauriac and Albert Camus wrote their articles and sent them into the atmosphere of the heights where they stood, with an acuity of analysis that made them respected by all. Within the newspaper, they lived together without really crossing paths. Opposed to each other at the time of the purge, on the question of the fate that should be reserved for the writers who collaborated, they seemed above all separated by the relationship they had with the Catholic religion. François Mauriac had made his faith and the universal message of Christ the only landscape where he was sure never to get lost. According to him, by virtue of the humanist principles which should in all circumstances guide every Christian, there could be no justice without charity. The one his detractors had nicknamed – who knows why! – “the elegiac old crow” wanted to save Brasillach from death, even though the extreme right, during the war, had constantly threatened him with it. Pleading in General de Gaulle’s office the cause of writers who had compromised themselves, he came out disappointed, on the grounds that he had met a “cormorant” there. Visibly exceeded by the excess of humanity of his interlocutor for beings who, under the German occupation, had shown so little of theirs, de Gaulle had remained unmoved.

Albert Camus had not shown such charity at the end of the war and a conflict with Mauriac had arisen. But when the Algerian war had presented itself as the cruel dilemma of his life – torn between the irrepressible love of his native land and deep moral convictions which could only lead him to reject the very idea of colonization –, he had this formula which could have brought him closer to the Bordeaux academician, if Christ had managed to inspire him with a word: “Between justice and my mother, I choose my mother…” Between these two beings, whom everything seemed to oppose, and who gave the feeling of corresponding with each other beyond time and death, seemed to pass the irresistible and warm breath of all French universalism including the humanists, in the diversity of their currents , considered themselves to be the trustees.

“As a playboy that he was, he readily apologized for his cruel outbursts, laughed up his sleeve, and like an eternal capricious child, returned to the charge to finish off his prey.”

The freedom of tone did not then suffer from criticism. It was a trait of civilization to which the talent of the pen gave a timeless panache. It was often said of Mauriac that he could be wicked. He himself assumed that his feather could turn into a point and hurt his target. Playboy that he was, he readily apologized for his cruel outbursts, laughed up his sleeve, and like an eternal capricious child, returned to the charge to finish off his prey, presenting it in grotesque ways. As a writer-journalist, he attributed to his talent for writing what his detractors attributed to his ferocity. In the sum of articles that constituted Notepad and of which L’Express was the glorious setting, we saw the most established figures of the Fourth Republic lose their luster: the eternal Minister of Foreign Affairs, Georges Bidault, was thus frozen forever, “hung on the railings of the Quai d’Orsay”, while the President of the Council Joseph Laniel found himself reduced to the inert mass of a safe, since “there was ingot in him”. Pretensions to modernity were also unceremoniously flushed out: Jean Lecanuet, all seduction, saw himself limited to the impotence of his smile, and Mauriac even evoked his name, which “delivered an unpleasant sound” to his ears. In well-ordered receptions, the wife of the writer Daniel-Rops – who was the author of a life of Christ – had heard himself whisper in his ear, while Mauriac stroked his coat of mink, “sweet Jesus…”. So was François Mauriac, mischievous as Jean Cocteau liked to describe him, when he represented him as a “young colt”.

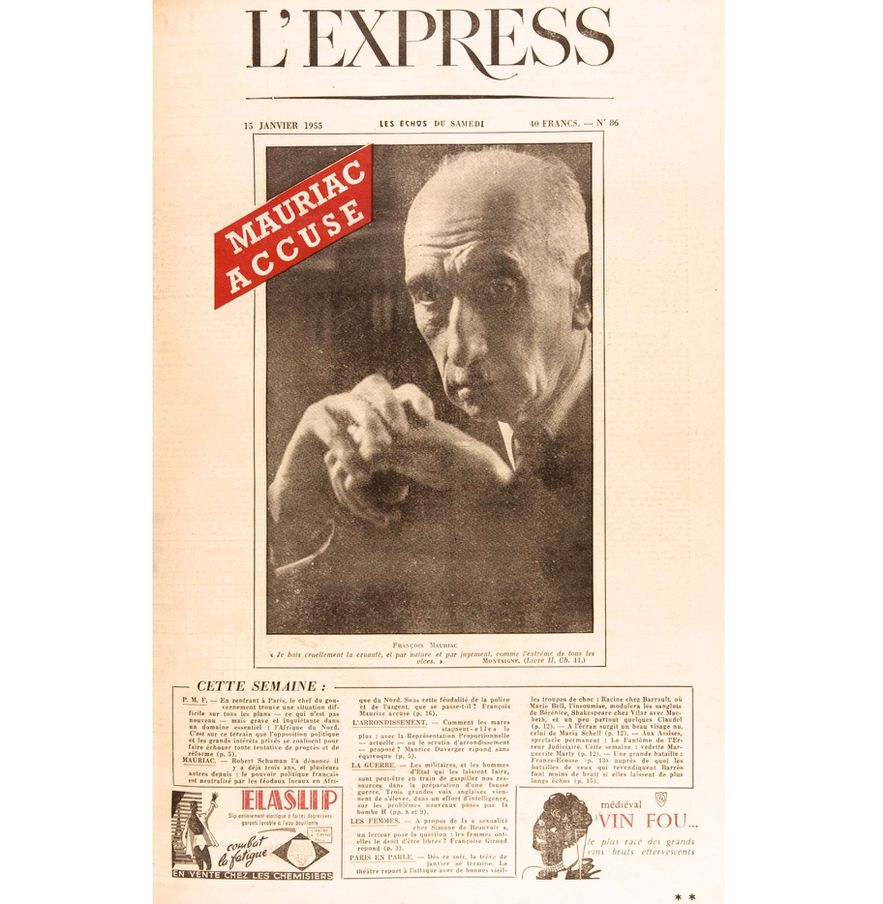

Cover of L’Express n° 86 of January 15, 1955.

© / THE EXPRESS

But overhanging this gallery of portraits, which showed a sagging political regime and a personnel above all preoccupied with maintaining itself – the MRP had been renamed “a tramway called power” –, a few figures floated, who received the unconditional encouragement of the Bordeaux academician: Charles de Gaulle, “a madman who said France to me” and who made no one laugh “because it was true”; Pierre Mendès France, who had had the courage to engage under the jeers of Parliament the process of decolonization in Indochina, in a tireless quest for the truth, which was so cruelly lacking in all the others; François Mitterrand, to whom he was linked by the memory of 104 rue de Vaugirard and an undisguised interest in romantic destinies.

François Mauriac judged on paper. As a journalist, he never stopped at appearances and showed little interest in where people were talking from. He retained from their speeches only what they deeply meant and detected in them the share of sincerity and the propensity to hypocrisy on which he shed light, by plunging a torch into the darkness of the human soul. The Catholic bourgeois, whom the conservatism of his family predestined to conformism, put his pen to the service of the most just positions. He won his freedom through his fights. If he was expected to run after what everyone else wrote, one was happily discovering that herding was not what he succumbed to. On the invasion of Ethiopia by Mussolini’s Italy, on the war in Spain where the clergy lost its honor, on colonization, the impasses and dishonor of which he tirelessly denounced, he had the thought of a just . Not because he had talent, but because having a lofty idea of the mission of the journalist, he worked while keeping a healthy distance from mediocre outbursts. One day, out of Gaullism, he left L’Express. Those who had loved him so much, and had summoned him, saw him depart with heavy hearts. They did not hold him back. Nothing can be done against the will of a free being.

*Bernard Cazeneuve was Minister of the Interior from 2014 to 2016 then Prime Minister until the end of François Hollande’s mandate. This year he published a book, My life with Mauriac (Gallimard), in which he recounts his unexpected companionship with the journalist and writer from Bordeaux.