For several months, weak signals have followed one another in China. In July, the National Bureau of Statistics (BNS) published a consumer price index that contracted by 0.3% over one year, while producer prices fell by 4.4%. For this second indicator, the figure is a slight improvement compared to June. Not enough to call into question the difficulties accumulated by the world power since its rebound at the start of the year, following the end of the “zero Covid” policy. A teacher of Chinese economics at the National Institute of Oriental Languages and Civilizations (Inalco) and associate expert on Asia at the Institut Montaigne, Philippe Aguignier sees in these data the new illustration of a structural problem in the country’s economy. .

L’Express: The decline in the consumer price index in July raises the specter of deflation in China. How to explain such a situation?

Philippe Aguignier: The consumer price index is not the only one to be negative compared to a year ago. That of producer prices is too. Although these signals are spectacular, they should not be over-interpreted. There is no generalized deflation in China, and it is not impossible that the situation will ease a little in the months to come. Only the real estate sector, which accounts for 20 to 30% of the Chinese economy, seems to have entered a spiral of self-fulfilling expectations with deferred purchase and investment decisions, after a period of overinvestment financed by debt. However, these signals reveal to the world that there is a real structural problem in the Chinese economy. Many people wanted to believe that once out of the zero Covid nightmare, China would start again. But the country has to face a lot of headwinds, including the question of demographic decline, which is only in its infancy.

So is the Chinese slowdown sustainable?

We have been certain of a slowdown for some time, which is not surprising: no economy can sustain a 9-10% growth rate in the long term. However, China remains a growing economy. The 5% growth rate announced by the leaders for this year will, in my opinion, be achieved, all the more easily since it was flattered by a favorable comparison effect, after a particularly weak year in 2022.

However, is the current crisis a sign that the Chinese model is outdated?

China’s economic model has indeed worked for a very long time, but has led to certain excesses and imbalances. The country suffers from a high level of debt and structurally weak domestic consumption. Today, the country needs to undertake fundamental reform.

How does the central power react to this situation?

So far, the government seems to want to avoid resorting to its default response in previous episodes, which has consisted of big investment plans, and which only postpones the problems. The leaders seem ready to accept that the economy is rocking, and not just a little. They seem to be aware of the problem of real estate, the level of indebtedness of this sector and as well as that of local governments. It remains to be seen how long this policy will last and what the response will be in the long term.

Is the debt burden likely to become insurmountable for China?

Including central government, corporations and individuals, debt in China is around 300% of GDP. From a macroeconomic point of view, the country still has room for manoeuvre. The problem with this debt is its composition and its distribution: it is concentrated on those who have the least capacity to repay it. Part of the state enterprises are thus artificially kept afloat even though they are not profitable. As for the local governments, the difficulties are accentuated in certain regions, in particular in the North-East, historically prosperous zone, but in the process of becoming one of the poorest of the country.

Chinese car manufacturers have taken on many markets, particularly in Europe. Is the collapse of domestic demand likely to accelerate the international deployment plans of local companies?

Since there is not enough domestic demand to absorb the supply, Chinese industry will effectively spill over to the outside world. The phenomenon has already been observed in the case of solar panels. China is now in a quasi-monopoly situation: it has been a bloodbath in Europe and the United States, but also in China, where many companies have gone bankrupt. The automotive industry has reason to be concerned. Europe, and to a lesser extent the United States, will be affected by a decrease in demand from China and by heightened competition from Chinese manufacturers in certain segments. In the medium term, it is also possible that the country will flood the world with its production capacities in semiconductors using mature technologies.

With what consequences in the rest of the world?

For commodity-producing countries, of which China is obviously one of the big customers, there may be a decrease in demand, without it necessarily being a collapse. Who says less demand certainly says falling prices and potentially abandoned investment projects, even if the phenomenon has not yet been observed.

China is the biggest emitter of CO2 in the world. Is the slowdown in its economy likely to call into question its ecological transition?

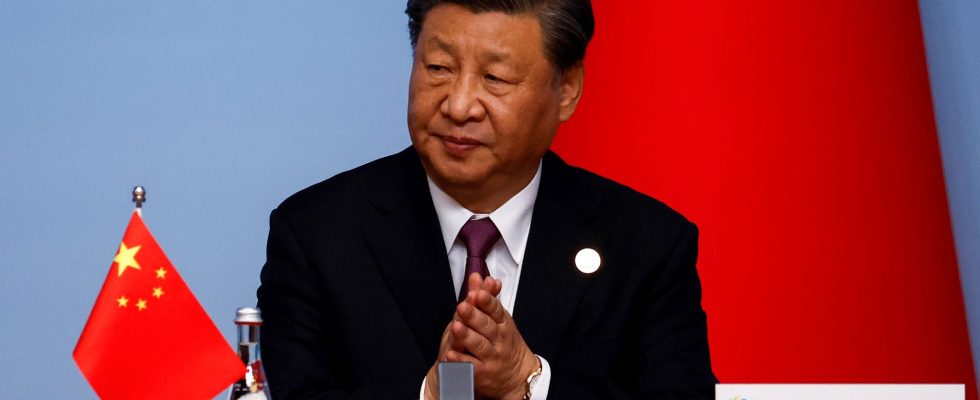

I think the leaders are aware of the fact that the country is very exposed to the problem of global warming. Their desire to reduce their emissions seems real to me, even if the situation is paradoxical: China is investing in renewables while continuing to finance coal-fired power plants. Xi Jinping was clear during John Kerry’s visit to China a few weeks ago that no one will dictate China’s pace on decarbonization.