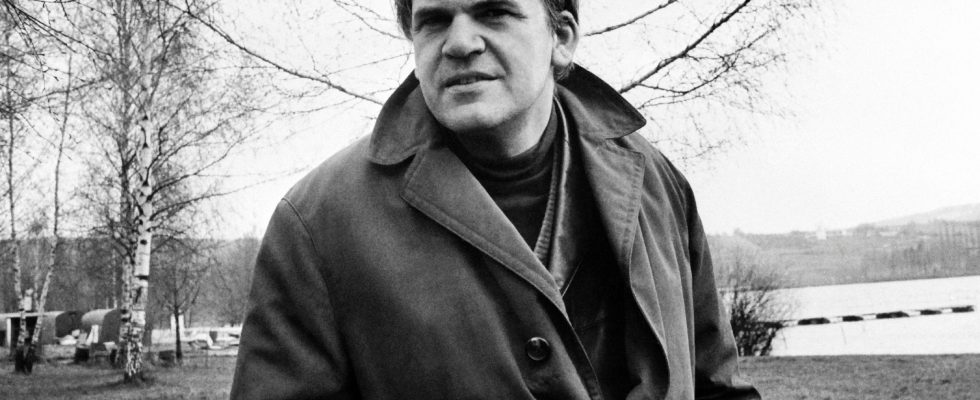

Milan Kundera was born in Czechoslovakia. In 1975, he moved to France. He dies in Paris. If I wanted to live up to my admiration and respect, I would have to stop there, list his work, and good evening. Because Milan and Vera Kundera, his wife who was his homeland, his protector, his inspiration and so much more, conscientiously destroyed all the manuscripts, all the contracts, all the correspondence, all the material that could be of use to a future biographer. All that will remain of Milan Kundera is his Work, 11 novels, four essays and a play gathered in two volumes of the Pléiade, which contains neither critical pageantry, nor biography of the author, nor notes. What is unique.

There will also remain 2,374 pages of minutes which constitute the grotesque surveillance of Kundera and his wife by the Czech political police between 1970 and 1985, archived at the Institute for the Study of Totalitarian Regimes in Prague. “I don’t like doing the melodrama of my life,” Kundera said. All right. He said he was “overdosing on himself” while promoting his most-read masterpiece, The Unbearable Lightness of Being, in 1984, which decided him to stop interviewing. The novelist no longer exists except behind his work, his novels, his words. Because he was above all a novelist, not a writer, a novelist who is “an attitude, a wisdom, a position excluding any identification with a policy, a religion, an ideology, a morality, a community”.

“The police destroy private life in communist countries, journalists threaten it in democratic countries”: Kundera, a man of the 20th century, could only be a critic of modernity, he who could not bear the moans of “me, me, me” mantra of autofiction and the permanent staging of oneself, the lamentable spectacle of the navel which is self-sufficient and does not seek to give birth to the world, he abhorred transparency, this self-inflicted totalitarianism for everyone’s misfortune.

A “Mitteleuropean” story

Kundera is a European story, a “Mitteleuropean” story. His father, a pianist and musicologist, imagined him a career as a musician, Kundera too, who took lessons in musical composition at the age of 10 with Pavel Haas. This one, of Jewish confession, friend of his father, after having lost his apartment, continues to give lessons of furnished in furnished to finish deported first in Terezin then Auschwitz where he dies in 1944. A handful of years more Later, Milan Kundera first married the daughter of Pavel Haas.

Kundera will first be a poet and a Party writer, like any ambitious young man with a touch of humanism. It was he who in June 1967 inaugurated the Congress of Czech Writers. But a year later, in the middle of the Prague Spring, when censorship was abolished and he had just received the Czech Writers’ Union prize for the sublime Joke, Soviet tanks enter Prague. It is his wife Vera, a TV presenter, who announces the invasion of Russian troops.

In 1969, Vera was fired from television and Kundera from university, his books were withdrawn from bookstores and libraries, he was erased from his native country. Thus was born the first misunderstanding that will propel him onto the international literary scene and make him what he hates: “A committed intellectual.” Kundera sums it up with an ironic: “To everyone, I was a soldier mounted on a tank.” Huge joke!

In 1975, it is the definitive exile, then the transition to French as the language of writing. Unique again.

Kundera, who defines Europe as “the maximum diversity on the minimum space” in a premonitory article, “Un Occident kidnappé” (1983), is the novelist of this cosmopolitan, refined Europe, which was nearly crushed by the Ottoman Empire, Germany, Russia, but which survived through the power of culture. Europe is more than a history and a geography, it is a culture. Let’s say it again.

To read Milan Kundera today is not only to rediscover the 20th century, to understand the spirit of Mitteleuropa made up of cheerful melancholy, to understand why Kafka is a comic and not a tragic writer, to be part of the long, tortuous and powerful history of the novel, therefore of the West. Above all, it’s breathing life into freedom and suddenly remembering why censorship is never good for any cause, why man is made up of nothing but uncertainties and contradictions, and being proud, so proud , to be a European of which Kundera offered the finest definition. “European: someone who is nostalgic for Europe.”

* Abnousse Shalmani is a writer and journalist committed against the obsession with identity