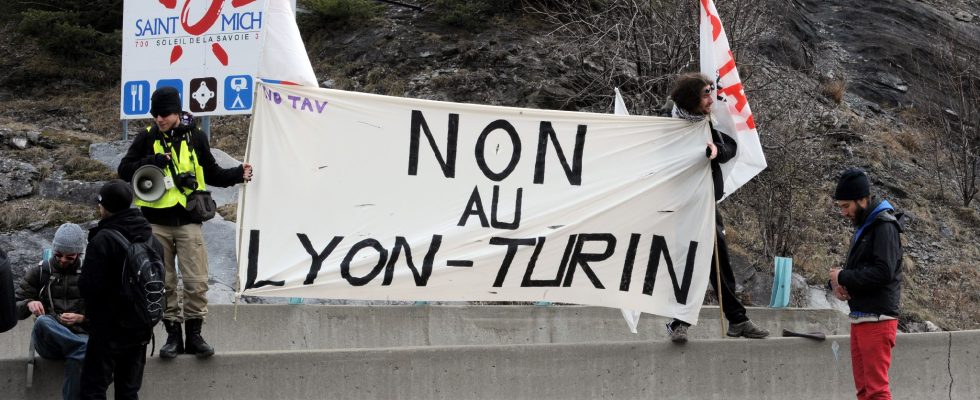

Stéphane Guggino is general delegate of the committee for the Transalpine, an organization created in 1991 which brings together public authorities and railway companies campaigning for the construction of the Lyon-Turin tunnel. This structure, chaired at the outset by Raymond Barre, continues to push in favor of the new line project. But today, his spokesman admits to being overwhelmed by the turn of events. In his view, the right questions are not being asked. The old erroneous discourses on the ecological impact continue to be repeated in a loop, fueling the dispute. Thus the collective Les Uprisings of the Earth calls for two days of demonstration this weekend against the tunnel. It is nevertheless one of the most important projects in Europe in terms of carbon-free transport. Atmosphere.

The Express. Why is this railway line project taking so long? Is it above all a financial problem?

Stephane Guggino. Only in part. On the French side, the digging of the tunnel under the Alps is progressing and gaining momentum. With regard to the access roads to the cross-border structure, a declaration of public utility was made in 2013 but since then nothing has been done. We mainly discussed, exchanged… At first, everyone had their eyes riveted on the tunnel without really worrying about access. Then when the tunnel passed the milestone of irreversibility, we realized that there was still a section of 140 kilometers to complete. And since then, we procrastinate. You are right, one of the problems is financial. The State which supports the central part of the line (the one which passes under the mountain) wishes that the communities co-finance the part linking Lyon to the tunnel. In total, France must find 5 billion euros over 20 years, the rest being borne by Europe and Italy. But if our country is not able to finance such an amount, it is worrying.

The Italians are just beginning to get exasperated by the delay taken by France

Well Named. On the Italian side, it has been five years since the project for the access roads to the cross-border tunnel was finalized on a technical level. Funding and operating model are clearly detailed. On the French side, we are very late. Arbitrations between the different route scenarios linking Lyon to the entrance to the tunnel are still pending. At the beginning of the year, a report proposed to postpone the access routes beyond 2045 and to be content, until then, with renovating the historic Dijon-Modane freight line. However, local communities do not want it. Especially since it is not calibrated to receive a sufficiently large volume of goods… When the tunnel opens in 2032, the Italians will be able to pass 162 trains per day, at a so-called P400 gauge allowing the bulking of freight. On the French side with Dijon-Modane, we would be at less than 100 trains per day with a lower gauge. In other words, if nothing changes you will have a huge pipe connected to a tiny tap. France risks becoming a bottleneck. A few days ago, Minister Clément Beaune gave a positive signal by recalling the importance of access to the tunnel. He also released three billion euros. But without giving a timetable.

Is Europe getting impatient too?

Absolutely. Europe, like Italy, is asking us to take a clear decision. Today, a train takes 4 hours to travel the 270 km that separate Turin from Lyon. You spend less time in the car. With the new line, the journey will take two hours. But by broadening the focus, the tunnel becomes a link connecting the European transport networks between Eastern and Western Europe. It is one piece of a much larger puzzle. We say Lyon-Turin but in fact it is also Paris-Milan or Barcelona-Milan. As part of the Green Deal, Europe aims to break the bottleneck in the Alps and connect thousands of kilometers of routes. In this context, it hardly appreciates the lack of French decision-making when it offers considerable funding.

How to explain the apathy of French decision-makers?

The socio-economic profitability of a project like Lyon-Turin can only be assessed over the long term. It does not necessarily correspond to the political horizon. Moreover, there are a few cogs at the heart of the central administrations which do not always appreciate, despite appearances, having to align themselves with the European strategy. Finally, and this is perhaps even more problematic, the Lyon-Turin is still considered from Paris as a regional project even though it is the largest European low-carbon mobility infrastructure project for passengers and goods. ! If it concerned the Paris region, one can imagine that things would go faster. We are therefore facing a paradoxical situation: the project on the French side is progressing in slow motion while more than 80% of the population wants it to be accelerated. All local elected officials except the ecologists and La France insoumise, support the initiative.

The call for demonstrations this weekend risks aggravating the situation. What do you think of the ecological arguments put forward to stop the project?

Ten years ago, a handful of far-left activists constructed a narrative that has since traveled everywhere, culminating in this weekend’s protest. However, the Swiss, a few dozen kilometers away, have built three tunnels comparable to the one currently being dug. Thanks to these infrastructures, they removed 70% of the goods from their route to put them on the rail. There, even environmentalists are delighted with the result. Especially since there was no problem with massive water drainage or dried up springs. In France, Jean-Luc Mélenchon said that the Lyon-Turin tunnel “empties the water from the Alps which falls into the hole that is dug”. And incredibly, this sentence is repeated over and over by opponents even though it does not have the slightest scientific validity. In truth, water runoff remains closely monitored by the project owner TELT in conjunction with the authorities. But why would the tunnel lead to a series of disasters here and not in Switzerland?

The other argument of the ecologists concerns the ecological impact of the construction site. Can we quantify it?

A project of this scale always has an impact on the environment. But it must be measured on the scale of the lifetime of the infrastructure. In all cases, the ecological balance is positive. It would take about fifteen years to cushion the impact of CO2 emissions. At the end of this period, the structure would save one million tonnes of CO2 per year over 150 years (the life of the infrastructure). It is the equivalent of a city like Nice or Montpellier. However, these arguments do not want to be heard. Other figures circulate. Some come, for example, from a report by the European Court of Auditors. Except that the passage in question was written by an expert who turned out to be a figure of the biggest French road lobby! By officially seizing the European Court of Auditors, which recognized that the analyzes were only binding on its author, the Transalpine committee was able to lift the hare. But the misinformation continues. We are no longer rational.