Isamu Noguchi (1904-1988) comes from a double culture, born of the liaison between the American journalist-author Léonie Gilmour and the Japanese poet Yonejiro Noguchi. The relationship ends in a phantom marriage (its reality remains nebulous) shortly before his birth. Isamu spent his childhood in Japan, before joining, as a teenager, the United States, where he trained in sculpture. At 24, direction Paris. There he became the assistant of the Romanian sculptor Constantin Brancusi and frequented the figures of the avant-garde, including Alexander Calder. “You belong to this generation which will go directly towards abstraction without having to free itself from nature as mine had to do”, predicted Brancusi. Is pure abstraction really progress? wonders Noguchi, before deciding that it is rather a question of “something which continues and which permeates the time”.

While France remains his anchor, he travels the world to meet the creators who will feed his inspiration, from the master of Chinese calligraphy Qi Baishi to the choreographer and dancer from across the Atlantic Martha Graham, passing by the American architect Richard Buckminster Fuller. Eurasian, he suffered racism both in Japan and in the United States and “conceives his creation as a quest for identity allowing to forge links between individuals”, point out the curators of the exhibition at LaM (visible until July 2 ), Sébastien Delot and Grégoire Prangé. From the 1930s, Noguchi became interested in public space, designing monuments and buildings, then design. Its lights, including the famous Akari lamp in washi paper on a bamboo structure created in 1952, a fusion between traditional Japanese art and the most contemporary forms, have met with incredible success.

Isamu Noguchi, “R. Buckminster Füller” (bronze, chrome plate), 1929.

/ © The Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum / Penn State University Libraries / ars-adagp, Paris, 2023

But Noguchi’s big business is the relationship between sculpture, space and body. Hence his fruitful collaborations with the stage. The first, in 1926, with Michio Ito, pioneer of modern dance, down to his fruitful contributions for Martha Graham. For three decades, he participated in the sets and costumes of the latter’s opuses, going beyond the borders between East and West to embody “an open and decompartmentalised vision of art which, even today, influences contemporary creation. “, underline the curators.

Through dance, sculpture can “exist in the hypothetical world of theater as one of the living elements of human relationships,” Noguchi rejoices. Graham, he will claim, used his sculptures as “an extension of his body”, much like Spider Dress and Snake, shaped in brass and bronze wire, which she deploys in her room Cave of the Heart. A long-term association that the Popess summarized in her biography published in 1991: “Isamu brought me his conception of space, the intimacy of an object on the stage”.

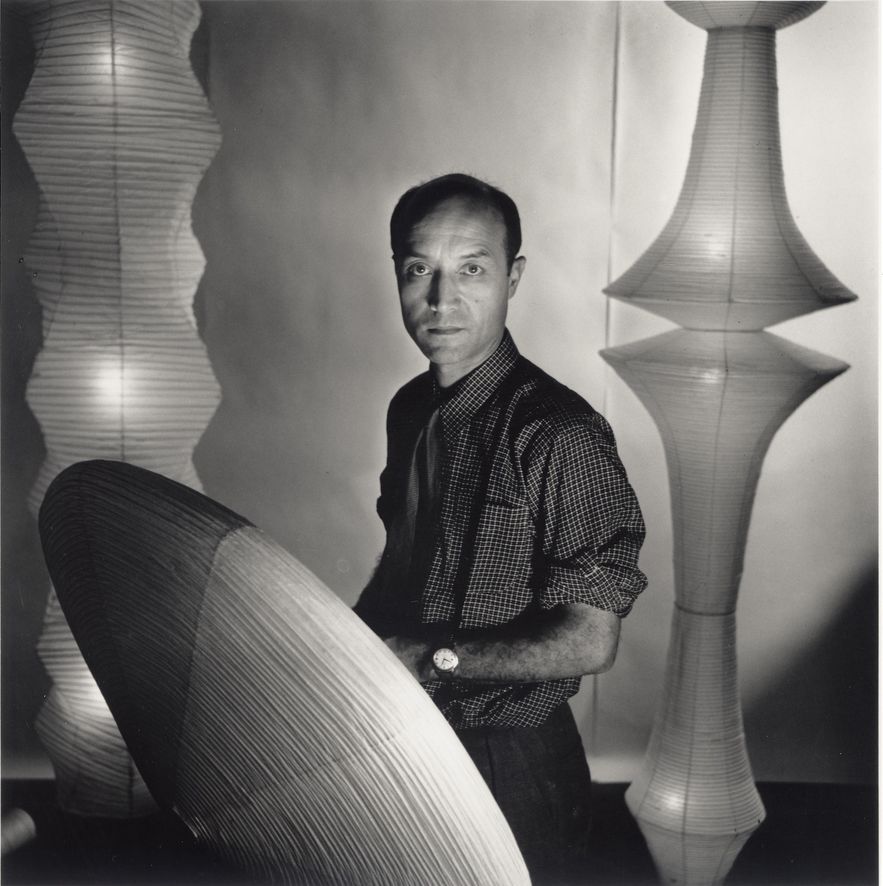

Louise Dahl-Wolfe, “Portrait of Isamu Noguchi”, 1955.

/ © Center for Creative Photography, The University of Arizona Foundation / The Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum, New York / ars-adagp, Paris, 2023

At LaM, the photographic or filmed testimonies of his work alongside the choreographer are fascinating, like those carried out with other innkeepers of the genre, such as George Balanchine or Merce Cunningham. Noguchi, who defined himself as an “architectural sculptor”, placed the body and the human at the center of his work. And when he posed in his studio for the photographers Irving Penn or Lee Miller, it was with his own body that he played, turning into a “sculpture among sculptures”. A sort of “total creator” who has sought throughout his career to push the limits of statuary in a century rich in cultural and societal upheavals.