Started for more than a year, the war in Ukraine highlights the weaknesses of the Russian army, still formatted by the Soviet model. This Red Army, dissolved in 1992, the historian Jean Lopez examined it from every angle in works crowned with numerous prizes, including Barbarossa: 1941. Absolute War (Past Composed), Greatness and misery of the Red Army (Threshold) and Stalin’s Marshals (with Lasha Otkhmezuri), published by Perrin. He explains to L’Express how Putin’s way of commanding as a warlord – through fear and a very vertical command – echoes other episodes in Russian history. As for the decision of Evgueni Prigojine, the boss of the Wagner mercenary group, to recruit in prisons, it is also part of a great Russian-Soviet tradition.

L’Express: Does Putin direct his generals like Stalin did?

John Lopez: We know nothing of the relationship between the sovereign Putin and his strategists, that is to say the generals in charge of the war. What we can say is that, by tradition, since the tsarist era, whether under Peter the Great or even under Nicolas 1st, the Russian sovereign has always tended to take his role as leader very seriously. armies. This continued in Soviet times and we find this with Putin, leader of the Russian Federation. He also commands through fear, even if we do not find the level of terror reached under Stalin. Russian military leaders tend to give in very quickly to the desires of political power.

What do Stalin’s army and Putin’s army have in common?

That of Stalin had undergone in the 1920s and 1930s an extremely rapid modernization of its methods of combat and its equipment. We went from a peasant army, of infantry and cavalry to a very heavily mechanized army, equipped with a mass of artillery and armored vehicles, and a plethoric air force. The Red Army also had great difficulty in dominating this cultural and material revolution, which partly explains its setbacks at the start of the Second World War. Today, the Russian army is also in a period of transition, between a mass army where quantity prevails over quality and a reduced format, professional type army, which it has difficulty in putting implemented, with contemporary equipment, more precise, more efficient. The war in Ukraine caught him halfway.

What about the type of command?

Putin’s army has retained a very vertical command. Officers have little incentive to show initiative. The military power undergoes the very close constraint of the political power, but it itself exercises a very tight control over its own corps of officers. The Russian officer tends, when the unexpected occurs, to be a little helpless and to turn to his superiors to know what to do. He has not received training focused on the capacity for initiative and taking responsibility. This was already true in the time of the tsar.

Does the use of mercenaries and convicts, with Wagner, contrast with the way of waging war under the Soviet Union?

As for mercenaries, there was nothing like that in the days of the USSR. We have to go back very far, to the 17th century, to find troops of mercenaries whose pay is paid by the Russian State, in the service of the Tsar. As for the use of prisoners who are offered the possibility of redemption, this was also found in the time of the Tsars. It was a way of getting rid of bad subjects, until the adoption of conscription in 1874. Stalin took this to a higher degree during the Second World War, when a million prisoners of common right – political prisoners – were taken out of the gulag. They were sent to normal Red Army units, not disciplinary battalions. Until Gorbachev, there is evidence that the command was recruiting up to 50,000 ex-convicts a year to achieve its goals. When Wagner’s boss, Evgueni Prigojine, goes to recruit in prisons, he is therefore part of a great Russian-Soviet tradition.

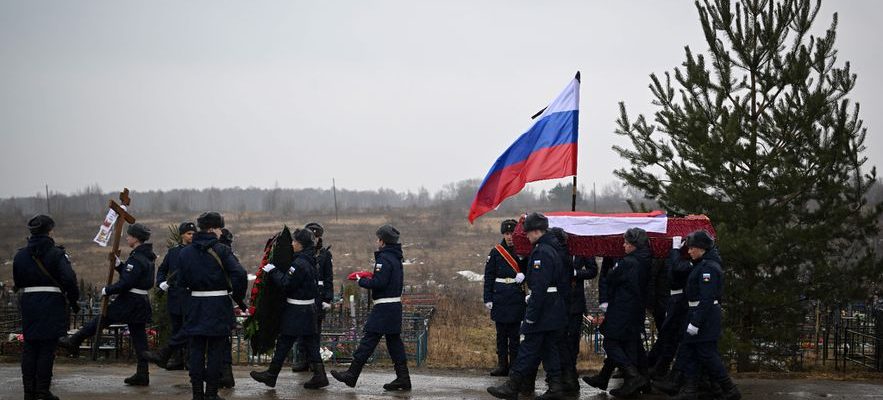

The funeral of a Russian soldier killed in Ukraine, March 24, 2023 at the cemetery in Bogoroditsk, Russia

© / afp.com/Natalia KOLESNIKOVA

You have just written a book with Benoist Bihan, Conducting war: interviews on operational art (Ed. Perrin), a theory conceptualized by General Alexandre Svietchine (1878-1938). Do we find his thoughts on the Ukrainian battlefield?

The strategy sets the objectives pursued by the war. On this basis, “operational art” strives to organize military activity (combats, battles) into operations. But for this to work, the strategy must itself be adapted to the situation. If the strategy is flawed, like that of the Red Army in 1941, which continued to attack in the face of the German invasion, the operational art cannot lead to victories.

Against Ukraine, the strategy of the Russian army was to put an end in a few days to a Ukrainian military system judged, wrongly, to be bad. The Russian command underestimated its adversary, it believed that it could overthrow it in a single operation. But Svietchine teaches that the strategy of annihilation can only succeed very exceptionally in history, and supposes that the adversary is very weak or does not have the will to fight. Sviechin says that success more commonly involves a strategy of attrition, with military activity being cut up in time and space into a series of operations until the final goal is achieved.

This failure of Putin’s army is reminiscent of that of the Red Army when it tried to seize Poland in 1920…

The general who commanded it, Tukhachevsky, thought he could destroy Poland in a single operation carried out in depth. He thought, and with him the politicians, Lenin first, that the Red Army would be helped by the uprising of the Polish workers because it was their class interest. A fine example of how ideology can shape the strategy implemented. Same thing in November 1939 when Soviet soldiers attacked Finland. It is then explained that the Red Army, in a single operation, can take Helsinki, because the Finnish proletariat will open the doors to it. There too, a big disappointment: this catastrophic error will be paid for by 140,000 deaths.

At the beginning of the “special military operation” in Ukraine, the Russian soldiers were told that they would hardly have to fight, because they were going to liberate a people from a band of Nazis and they would be welcomed as brothers, as liberators. We know this from the conversations captured on the telephones and the interrogations of prisoners. This may explain, moreover, that the entry into the war on the first day did not give rise to an outburst of violence, as if the chiefs had received the order to restrict the use of fire so as not to alienate the population.

During World War II, the material aid provided by the allies of the USSR played a big role in the success of the Soviet army. Today, it is no longer Moscow that benefits from it, but kyiv…

The Red Army benefited from a very important Anglo-American contribution in advanced fields which were beyond the reach of Soviet industry, such as military communication, optics, radars, but also modern trucks. All this gave this army the elements of mobility and better control of the mass, allowing it to achieve great victories from 1943. But we must not forget that it is also linked to the fact that Soviet industry beat Germany in the production of armor, artillery and aircraft, which was very unexpected. The Ukrainians do not have such an infrastructure and find themselves in a different situation, totally dependent on Western aid.

Can Russia replicate the same effort as in World War II?

For the then Soviet Union, the threat was existential and the effort expended was gigantic, probably the greatest of any European country. Under no circumstances will Vladimir Putin be able to obtain from his people what Stalin obtained from his. The motivation is not there. To use Trotsky’s word, the Soviet nation was then a “military camp”. This is not at all the case of Putin’s Russia.