“In front of the canvas, I have no idea”, wrote Henri Matisse on November 21, 1929, a few weeks before his sixtieth birthday. His paintings then translate his difficulty and his hesitations, as for woman with veil, where the paint scratched in places and the jagged lines reflect the crisis he is going through. Six years later, the triumphant curves of the dazzling Large Reclining Nude (Pink Nude), preserved in Baltimore and rarely shown in France, bears witness to the path traveled by the painter to reinvent himself.

How did this spectacular revival come about? This is what the Musée de l’Orangerie in Paris deciphers until May 29, in collaboration with two institutions: the Philadelphia Museum of Art and the Matisse Museum in Nice. The first got the ball rolling on its picture rails this fall; the second will make it its big summer event. The event is important because, despite the multiple exhibitions on Matisse, “it is the first specifically dedicated to the 1930s”, underlines Cécile Debray, director of the Musée de l’Orangerie, co-curator alongside Claudine Grammont, in Nice, and Matthew Affron, in Philadelphia.

Henri Matisse, “Corselet on a background of “Tahiti””, 1936.

/ © Estate of H. Matisse © Photo Allen Memorial Art Museum, Oberlin

At the dawn of the 1930s, Henri Matisse was therefore out of pictorial inspiration – he was content to draw. It is not for lack of success, its odalisques and Nice interiors establishing its notoriety. But the doubt is there, maintained by the retrospectives organized on his radical works of youth, including the monthly magazine Art books, founded in 1926 by Christian Zervos, echoes this. It’s a cold shower for the ex-wild cat who no longer roars and goes to the other side of the world to regain his artistic virginity: Tahiti, in the footsteps of Gauguin. Polynesia signs its resurrection on the canvas, even if he paints nothing on the spot but photographs all over the place using his Kodak. Shortly after, he met Albert Barnes, the wealthy American collector, who commissioned him Dancea series made up of shapes cut out of gouache paper, which the Orangerie illuminates with the hanging of unpublished preparatory sketches.

Notebooks of Art, 1931, n° 5-6.

/ © Editions Cahiers d’Art, Paris 2023 © Photo Musée d’Orsay, Paris / Sophie Crépy

“The future? I’m waiting for it”

Art books speaks. Along with Picasso, Matisse is one of the magazine’s emblematic artists, which considers them the leaders of the avant-garde. Meanwhile, Lydia Délectorskaya, a 22-year-old Russian immigrant hired by the master in 1932 as a temporary studio assistant in Nice, left her mark on the pictorial turn taken by her employer. Under contract for a few weeks, she finally embarked on a long-term Matisse cruise. Alternately secretary, model, coordinator and organizer of events, she posed, during the decade, for multiple paintings. She remained at his side until the artist’s death in 1954, and from 1935 recorded the dates of the painting sessions to follow the work as closely as possible. The history of art thus owes a great deal to the beautiful Lydia.

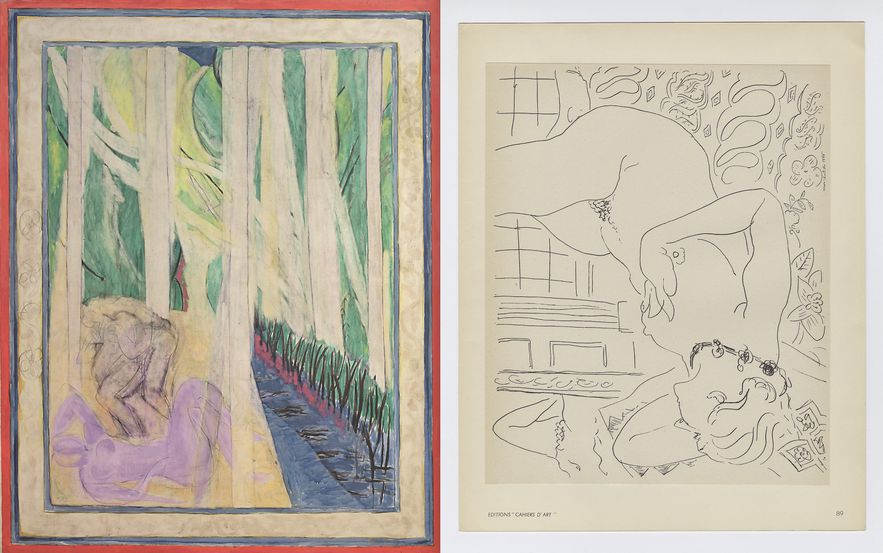

Henri Matisse, “Nymph in the Forest (La Verdure)”, 1935-1942/1943. To dr. : Cahiers d’art, 1936, N°3-5 (page 89), introduced by a text by Christian Zervos “Automatism and illusory space”.

/ © Succession H. Matisse © Photo Matisse Museum, Nice / François Fernandez – © Editions Cahiers d’Art, Paris, 2023 © Succession H. Matisse

1932 is also the year of the panel complex nymph in the forest, where the artist experiments with large charcoal drawings with Lydia as a model, which “express a form of liberated and rediscovered sensuality”. At the end of the decade, in Regina, he refined his vibrant colorful interiors with figures wearing Romanian blouses.

When the war arrived, while his peers fled across the Atlantic, the old beast chose to stay in France to capitalize on his pictorial resurrection: “I am at an extremely important point for my journey for which I cannot distract any force . The future? I’m waiting for it – whatever happens I won’t budge.”