When announcing on Twitter the publication of his latest scientific work, Dutch sociologist Thijs Bol copied Elon Musk. A small spade addressed to the American billionaire while his erratic decisions concerning the evolution of the social network are debated: the study in question, just published by European Sociological Review, deals with the correlation between level of income and level of intelligence, and makes the hypothesis of its disappearance at the top of the social pyramid.

Many studies so far published on the subject calculated, for a given level of intelligence, the average level of income of its “holders”, and concluded with a simple correlation: the higher the level of intelligence, the higher the average level of income of the individuals concerned was. Bol and his colleagues, the German sociologist Marc Keuschnigg, principal author of the study, and the Dutchman Arnout van de Rijt, reverse the perspective: they calculate, for each percentile (one individual in a hundred) of population income, the level means of intelligence displayed.

Their guinea pigs? Nearly sixty thousand Swedish men who, between the beginning of the 1970s and the end of the 1990s, responded to the entry into adulthood to cognitive skills questionnaires (verbal comprehension, logical tests, spatial reasoning, etc.) in as part of their compulsory military service. A mine of information that had already been exploited in 2018 a study of CEOs of large corporations which concluded that for each of them there were “a hundred times more men occupying managerial roles and displaying better combinations of qualities”.

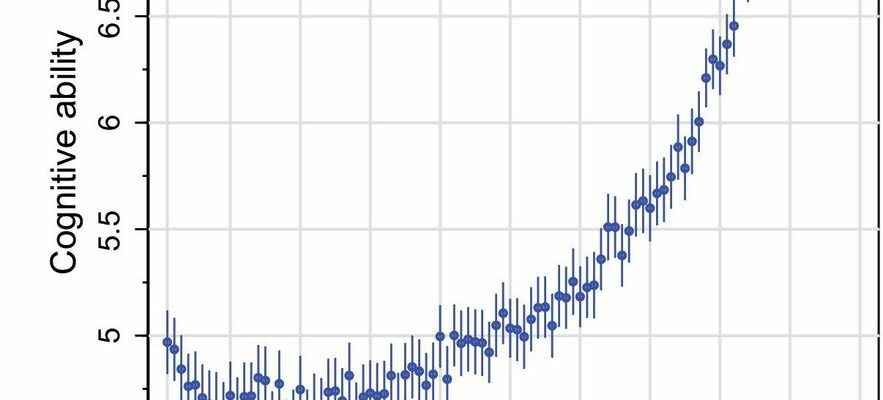

Keuschnigg, Bol and van de Rijt compare the results of these cognitive tests to the taxable salary, bonuses included, fifteen to twenty-five years later, around the age of forty. In the lower part of the curve, for incomes below the median income, they find no link with average cognitive abilities, measured by a score oscillating from 1 to 9. This becomes evident in the upper segment of the curve… except when you reach its summit, in the shape of a plateau. The average cognitive score peaks, around 7.25, for men who earn around $60,000 a year, but then drops slightly for the 3% who earn more than that. The top 1% of Swedish men earn an average of 7.15 on cognitive tests.

For each income percentile, the researchers calculated the average score obtained on the cognitive tests. The maximum is reached for the 97th percentile, ie individuals who earn more than 96% of the population but less than the richest 3%. (European Sociological Review)

© / European Sociological Review

“This does not mean that the most prestigious jobs are not demanding in terms of intelligence, or that the rich are stupid: we can clearly see that they display an intelligence above the average, summarizes Marc Keuschnigg. But their extremely high salaries are no longer justified by their intelligence and the selection for these ‘top jobs’ is not based on cognitive abilities alone.”

“Mathieu effect” and non-cognitive skills

But on what, in this case? When we question the sociologist, the first word he uses is that of “chance”. When embarking on their study, he and his two co-authors wanted to empirically verify an experimental study published in 2011 by two behavioral science experts, Jerker Denrell and Chengwei Liu, who hypothesized a performance/intelligence decoupling at both ends of the curve due to the ripple effect of success and failure. If two individuals have identical cognitive skills and an identical success rate in their professional projects, their final trajectory can be very different if one begins his career with a failure and the other with a success…

This cumulative effect of success, called in sociology the “Matthew effect”, is also one of the explanations put forward by Keuschnigg, van de Rijt and Bol on their discovery: “Luck can be having very good ideas at the start of your career and then experiencing a very steep career trajectory”, summarizes the first. But other chances are in play. That, for example, of being born into a family offering a network of contacts. When it is pointed out to Keuschnigg that others would call this chance “social capital”, he laughs: “Of course, as a Frenchman, you come to Pierre Bourdieu!” The author of heirs and of The distinction is also cited a few times in the study, which attaches great importance to the weight of elite networks: as part of an as yet unpublished extension, Marc Keuschnigg, for example, divided the sample into two halves, one urban ( large cities like Stockholm, Gothenburg…) and a rural one, and only found the income-intelligence “decoupling” in the first case.

By insisting on the importance of luck and networks, the study, summarizes its lead author, constitutes “a test of meritocracy, questions the fact that we really give the best paid, most prestigious and more important to the smarter people”. But cognitive capacity is not the only dimension of merit, and the researcher also hypothesizes a substantial role for non-cognitive skills (motivation, resistance to stress, creativity, etc.): a psychological argument which joins that of the researcher German Rainer Zitelmann, who told us recently that he saw among the super-rich many “non-conformists who like to swim against the tide”. As these assets would gain in importance, the weight of cognitive skills would diminish: “Academia, for which they are perhaps the most essential, is neither the best paid nor the most prestigious of professional sectors” , note, with masochistic irony, the three authors.

Women and immigrants

Merit, and the way in which it is rewarded, also varies according to societies, whether in terms of access to positions or remuneration (equal opportunities) but also of taxation and redistribution policies (the equalization of results). If Sweden is one of the most equal countries in the world, what if we conducted the same survey in the United States, for example? Conservative critics of the study ofEuropean Sociological Review believe that the strong Swedish redistribution can discourage the search for extreme performance and therefore blur the link between income and intelligence. Conversely, Marc Kuschnigg hypothesizes a lower plateau in the curve in Sweden, “the model child of meritocracy”, than in “more unequal societies where social origin, neighborhood birth, access to the education system play an even greater role in determining life trajectories”.

It remains for new research to determine this, and also to fill in two of the blind spots of this work, necessarily obscured by the registers of the defunct compulsory conscription: a minority, the immigrants; half of the population, women. “On the one hand, we can say that women and immigrants face more obstacles and discrimination in the labor market, that luck and privilege play a greater role in reaching the top, and therefore that the plateau effect will be even more important, supposes the German sociologist. Or, on the contrary, to say to oneself that all these obstacles mean that only the very best make it to the top and that we will not see a plateau for them. For once, between even more marked piston effect and even sharper overselection, the researcher has not yet decided.