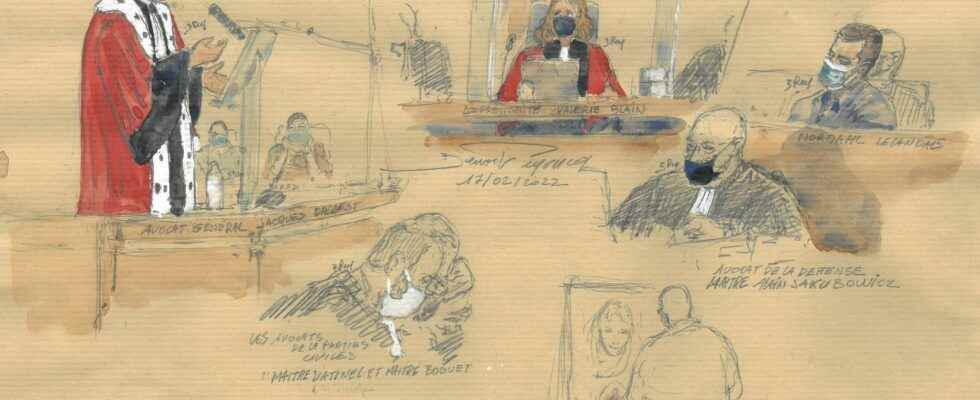

For more than thirty years, Jacques Dallest has been close to crime. As an investigating judge, public prosecutor and public prosecutor, his mission, throughout France, was to study criminals: their personality, their past, their background, their psychological state. On the basis of sometimes complex investigations, the magistrate had to identify the materiality of these crimes, determine their legal qualification, confuse the perpetrators. From organized crime in Corsica or Marseille to Nordahl Lelandais, against whom he requested life imprisonment as public prosecutor at the Grenoble Court of Appeal, he explains that he often found himself “in a singular face-to-face, disturbing, sometimes destabilizing but oh so fascinating”, with criminals, often banal figures, “desperately normal”.

During these three decades of career, Jacques Dallest has also known dozens of examples of unsolved crimes. “This extreme act which leaves the author in the unknown and is followed by no solution”, he describes in his book Cold Cases. A magistrate investigates (Mareuil Editions, 2023). He returns for L’Express to these definitively unresolved cases, these sometimes “edifying” miscarriages of justice, these perpetrators never identified or narrowly confused by the flash of lucidity of an investigator or a link suddenly discovered between two crimes. With a clear conclusion: “Despite all the energy it can deploy, the judicial institution must sometimes admit to being unable to provide the answers expected of it”.

L’Express: In March 2022, you recalled that 273 cases that could be qualified as cold box have been identified within the police services. What are the characteristics of these so-called “unsolved” crimes?

Jacques Dalest: Until recently, the unsolved crime had no real legal existence. It is the law of December 22, 2021 which created a specific title in the Code of Criminal Procedure, and which defines what is commonly called the cold box by “serial or unsolved crimes”. In short, these are murders, poisonings, acts of torture and barbarity, kidnappings, sequestrations and rapes, for which justice has failed to identify the perpetrator within eighteen months after the commission facts. There are several scenarios. In some cases, despite the initial investigation and the preparatory investigation, the crime cannot be elucidated for lack of identification of the perpetrator. In others, the alleged perpetrator can be identified, arrested and heard, but the courts lack the evidence to convict him. The alleged perpetrator may also die before confessing to the facts, forever depriving the families of a legitimate explanation. In some cases, the victim may also never be identified: in Marseille, I worked on a case in which investigators found the body of a woman inside a suitcase, which had been thrown on the lower port. We were never able to confirm the identity of this victim, and the file was never solved.

What factors can explain these cold cases ?

First, the crime scene setup can be complex. For example, if you find a body in the middle of the forest, you don’t know how far the crime scene extends. You can also find human remains, like this victim from Marseille: who is the victim, were there others? Then you can have human failures. An omission at a crime scene, negligence, a destroyed seal that should have been kept because potentially decisive, people never questioned when they should have been…

You can have negligence from investigators, or even magistrates who would have ordered the destruction of evidence, or who did not ask to assess things. I think the weakness of our system is the loneliness of the investigating judge. This loneliness is a bad adviser: it is absolutely necessary to pool thoughts, to consider together avenues that have not yet been considered… Between a solved file and a cold box, there may be a sheet of cigarette paper. The human aspect is very important. For Nordahl Lelandais, for example, the investigators had the idea of checking under the floor mat of his car, and they found a micro trace of blood! Another team could have missed it.

You also insist in your book on the notion of “criminal memory”. What do you mean ?

It is absolutely necessary that each magistrate and prosecutor have in their possession what I call “a criminal memory” that they could bequeath to their successors. Tomorrow, the prosecutor of Fontainebleau or Melun should for example be able to find on his computer the digitized files of unsolved crimes, to be able to rework them, to study possible links between the cases… This collective memory should also include spousal crimes, as well as disappearances. This does not exist today, even though there could be links to be forged between these cases.

Years later, investigations can be reopened thanks to new testimony, unpublished scientific evidence, a proven link between two crimes… But are there unsolved cases on which justice can’t come back?

The law of February 27, 2017 doubled the criminal limitation period, which increased from ten to twenty years: all files closed before February 28, 2007 can therefore no longer be the subject of new investigations, because they are definitively prescribed. Theoretically, that would not prevent the investigators from doing some research for the families, but legally, we could not judge the person concerned. However, there is an exception. If the case closed before February 28, 2007 is related in one way or another to another non-statutory matter, then it may be the subject of new proceedings.

Do you have the feeling that, in certain cases, justice has confessed itself powerless too quickly?

Of course. In the 1980s, files were closed after two years, which seems inconceivable today… But we cannot judge this timeframe with our eyes today, and with our technologies of 2023! At the time, it should be remembered that the investigators could not rely on DNA or the Internet. We weren’t necessarily looking to keep objects that could prove any link, we didn’t think in the same way. Today, the files remain open for five or ten years… We also work for posterity, to leave evidence for our successors that will still be accessible ten years from now.

You estimate in your book that only a few major cases are “inscribed in the tablets of history”, while the last decades have been marked by dozens of unsolved murders. Why do some files always raise questions, while others are forgotten in a few months?

It’s a bit mysterious, but you will notice that the murders of children leave a mark: little Gregory, little Marion, little Estelle, little Maëlys… The killings, like that of Chevaline, are also files that mark, because that they are very media-friendly, they arouse emotion. There is necessarily a catchy, sensational, enigmatic side that fascinates. But I don’t forget that every citizen can one day become an Assize Court juror, and have to judge a murderer or a rapist. People need to be informed about how justice works, and not stop at the “sensational” nature of a case.

You define the unsolved case as a “painful snub”, which sounds like “the admission of a collective failure” of investigators and justice. What is the unsolved case that has marked you the most?

I often cite the Muriel Théron case, which I was the first judge to investigate in 1993. A 17-year-old girl in Lyon was raped and then strangled on the hill of Croix-Rousse. I had received the parents who were devastated, and made every effort to find the author. At the time, I even did a helicopter flight over the place! A year later, I left my post as an investigating judge. Four or five judges succeeded me, without ever finding the author of the facts. The file was closed in 2012, then reopened thanks to an association which reworked the DNA found on the scarf which had been used to strangle the young girl.

Unfortunately, this DNA does not currently match any national police files. This file marked me because it could suggest that we had a predator in nature, someone who could have committed other crimes… I do not despair: the case was recently retransmitted to the famous pole specialized in Nanterre, created last year and specialized in cold cases.

You recall that a failure of justice is “badly admitted, badly understood and badly tolerated”. As a magistrate, how to manage this pressure of “the unresolved case”?

We try to tell ourselves that this is one file among others. And then, we are mostly taken up by other activities. At the time, I had a lot of cases to investigate, drug trafficking for example… But there are encounters that you don’t forget: I was marked by Muriel Théron’s mother, who seemed rather holding on at the time, and who I later learned died of grief.

I explain in my book that despite all the energy that justice can deploy, the judicial institution must admit sometimes unable to provide the answers expected of it. You have to admit it, admit it: there are no perfect investigations and sometimes the evidence leads nowhere. This can be badly tolerated because justice communicates quite badly, unfortunately. All this feeds suspicions, doubts, but we are not in a Cartesian and rational domain.

You note, moreover, that criminal sociology “demonstrates that the respectable citizen is just as capable of the murderous act as an individual reputed to be dangerous”. Does that mean anyone can kill?

The assassins that I have been able to meet are practically all good friends, respectable fathers, neighbors with whom we had nothing to reproach… Ordinary people. At first glance, a guy like Nordahl Lelandais doesn’t look like an assassin at all. Contrary to what some jurors think, there is no such thing as an “assassin’s physics”, nor even an “assassin’s journey”. There are certainly special lives, difficult childhoods. But most crimes are motivated by feelings of revenge, anger, hatred or humiliation. Humiliation is also the trigger that I put forward the most: it is dangerous, since I have seen that it can tip anyone into acting out.

On March 1, 2022, a division specializing in cold cases was created in Nanterre, made up of three specialized investigating magistrates and their teams, 100% seconded to these unresolved cases. Why was the creation of this center necessary in your opinion?

Since they are considered non-urgent and the magistrates simply do not have the time, these cases were often shelved in the courts. It was absolutely necessary that judges be entirely devoted to these cases. The Nanterre center will be responsible for starting from scratch for each investigation, but also for explaining to the families that, sometimes, justice has drawn a blank. Unfortunately, there is nothing more we can do. The creation of this specialized center is a first step. The specialization of a team of motivated investigators dedicated to unresolved criminal cases should be essential within judicial police units with a regional dimension. This is essential, because we know that serial killers or criminals who have never been identified can still operate in the territory. How many victims would have been to be deplored if we had never found a Nordahl Lelandais or a Patrice Alègre?