The story of this man is also that of a century. Through the fate of his character Valdas Bataeff, Andreï Makine condenses in his new novel, The old calendar of a love (Grasset), decades of Russian and world vicissitudes. False pretenses of tsarism, atrocities of the civil war between Reds and Whites, bicycle taxi rides in the Parisian host country, hardly heroic resistance under the French Occupation… A fresco of astonishing conciseness, but also the sensitive chronicle of a love: the bond uniting Valdas to Taïa, a smuggler met in Crimea, escapes the convulsions of history and the cruelty of men.

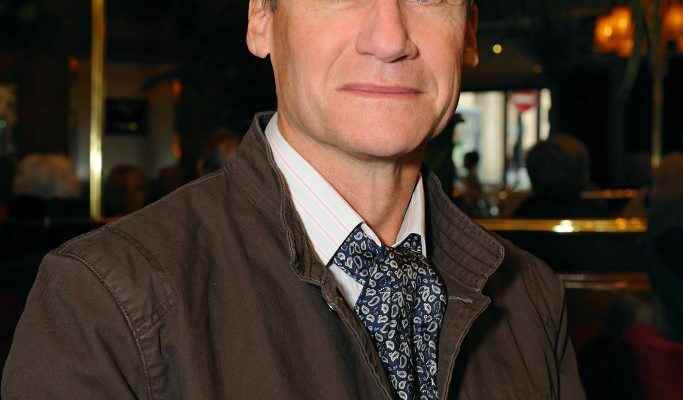

If the story was written before the start of the war in Ukraine, it echoes it in a disturbing way. A conflict about which the academician born in Russia and naturalized French does not hesitate to express himself, with a mixture of despondency and vehemence. At the risk of controversy. Interview.

L’Express: Your characters want to escape History, this “confusion of dramas and farces, atrocities and fugitive redemptions”, this “swirl of masks”. Do you share this disdain?

Andrei Makine : It’s not disdain but lucidity. I was born four years after Stalin’s death, in a Russia still very marked by the previous era. And I witnessed, near or far, the Cold War, just like the hot wars that bloodied the planet. I observed, like everyone else, the attempts at peaceful coexistence between the USSR and the United States, the decay of Sovietism, the fall of Communism. Like all my contemporaries, I witnessed a multitude of wars and massacres, while listening to great humanist speeches, so often contradicted by reality. Dostoyevsky’s wonderful wish, his mantra “Beauty will save the world” turns out, alas, invariably betrayed.

Your mantra is rather “Beauty allows you to escape the world”?

No, my characters do not preach romantic escape. Their wisdom is simple: Taïa, a rejected and wounded woman, saves the one she loves. A physical salvation as she protects Valdas. A spiritual salvation, because thanks to her, he guesses that another life exists, at the very heart of the worst atrocities of wars. Although the situation, like today in Ukraine, may seem hopeless.

Last March, you gave the Figaro an interview that earned you virulent criticism. You have been criticized for sending Europe and Russia back to back…

No, I do not put them on an equal footing. When I gave this interview, there were no European troops in Ukraine, that’s a fact. But for eight years, as Mrs. Merkel admitted, we had been trying to arm Ukraine and make it a NATO base. Without this threat, the war would never have taken place. Rightly or wrongly, the Russians have developed an obsessive attitude, telling themselves that once a member of NATO, Ukraine would have American missiles on its soil, which would put Moscow within minutes of their strikes. I am a radical anti-warmonger and in the interview with the Figaro, I explained that Europe, in my humble opinion, should do everything to become a sanctuary of peace, the only way out to avoid the third world war, which is increasingly probable. A continent free of blocks and military bases. The 100 billion euros that Mr. Scholz is going to invest in German rearmament could be used to fight against famine (3 million children die of hunger every year on the planet!) and against poverty, which now affects even the countries developed.

Before the start of the conflict, you were complimentary of Vladimir Putin. In 2021, for example, you stated in Current Values “You see Russia rising from its ashes, with its fundamentals of nationhood and spirituality. […] He’s not my hero, but he’s got what you’re missing: the visceral sense of homeland”…

I judge statesmen by their deeds, and according to those deeds my opinion changes, which is quite natural. As for the “visceral feeling of the fatherland”, this is the quality that the vast majority of Russians appreciate in Putin. Does seeing this automatically make you or me bloodthirsty henchmen of the Kremlin? Russians have a tragic memory of the millions of dead in World War II and seeing Nazi insignia on some uniforms in Ukraine or the Baltic countries brings back painful memories for them. Once again, to evoke it is not to pledge allegiance to some Stalinist nostalgia. The vision of the Russians is undoubtedly schematic but not devoid of meaning: the regime of predatory oligarchies under Yeltsin, which had ravaged the country (and it is not over!), has given way to a system that is certainly more restrictive but less anarchic. I do not need to point out to you that this authoritarian appetite is developing today on all continents, including Europe. The Russians are always afraid of a return to the warlike chaos that they have known all too well (Chechnya, Moldova, Georgia, Central Asia, Armenia, etc.).

In your opinion, the nuance is not audible when we talk about this conflict?

No. What matters today is to find a solution in Ukraine. The European Titanic sinks into a deadly conflict and the main thing is to save the castaways and not to stir up war and to organize round tables where the “experts” repeat like parrots: Putin is Satan and the Russians are monsters. This verbiage will not save those who die under the bombs. Exactly a century ago, the Russian Civil War ended. My book is about that time. One hundred years later, we are faced with the same tragedy. A century ago, civil strife in Russia was worsened by the military intervention of the British, Americans, Germans, French… Of those who could have worked in the search for peace. Instead, we preferred to carve up the territory of the dying Empire and covet this or that piece. I repeat, this is how the Russians of today see the situation and this observation, as you well know, in no way diminishes the judgment that you or I could pass on the terrible reality of the war that Russia leads in Ukraine.

But what you have been criticized for is not saying clearly enough that Russia was behaving in a monstrous way…

All wars are monstrous, I couldn’t be clearer. Or maybe, according to you, the American bombs – dropped on Japan, Vietnam, Serbia, Iraq, Libya, Afghanistan and dozens of other countries – yes, these carpet bombs do they seem more ethical and soft than the bombs thrown by the Russians? Instead of pursuing this macabre ping-pong on all the television sets (who is therefore the most frequent murderer?), let’s put all our forces to stop this war where Europe risks committing suicide. And let’s not let the Ukrainians become mere hostages of the Pentagon. The Ukrainian people deserve better than to suffer and die for the geopolitical interests of the power-hungry oligarchies.

To make the Americans responsible for the conflict, isn’t this, for the Russians, an admission of weakness and a strategy of diversion?

An American farmer on his tractor does not even know where the Donbass is. A Russian peasant has no hatred towards his Ukrainian brother. A worker in Kharkiv, Ukraine, does not hate a worker working in a factory in Siberia. On the contrary, workers, whether American, Ukrainian, Russian or French, have a natural solidarity with each other. But the ruling class seeks, as usual, only access to markets and the plunder of wealth.

But what to do, then, according to you? Your idea of a Europe protecting peace, whose two guarantors would be France and Russia, isn’t it chimerical?

No way. And de Gaulle understood it perfectly, without ever being complacent vis-à-vis the Kremlin. France and Russia, at two extremities of Europe, are called upon, if only by geography, to ensure its balance. If, at the time of the Minsk agreements, this Franco-Russian tandem had been able to function, the war, I repeat, could have been avoided. But here we are talking about geopolitics. However, for me, this terrible conflict is a permanent source of personal suffering. All my youth, I lived surrounded by many Ukrainians, I learned their poems and their songs. Knowing that their children and grandchildren are forced to die or kill is heartbreaking. And it is all the more tragic since, in 1991, at the time of independence, Ukraine was a prosperous country, with a solid industry and maintaining ties with Russia that could have remained fraternal, which would have been beneficial to both countries. In a few years all this treasure was squandered by a class of predators. And the Russians have no right to criticize Ukraine or lecture it because their criminalized elites behaved the same way during the 1990s.

Your book is a questioning of Russian identity, both haunting and untraceable…

The historical, economic, sociological reading grids, etc., respond less and less well to the great questions that arise before humanity, whose future teeters on the brink of fatal choices. This is why I write books that touch on the spiritual and existential essence of man. Admittedly, to evoke it in the midst of a culture of entertainment may seem at first destined to be heard by only a small number of readers – those who understand that our civilization, with its hubris of predation and unlimited material growth, is terminal. It’s easier not to think about it, following a football championship while in Ukraine the men are suffering and dying. But just imagine this hypothesis: we cancel all the matches, all the entertainment, all this despicable circus of political lies, and people of good will, believers or not, rise up against the conflicts which are ravaging the planet. We would so much like to see the representatives of the great religions stand up in Ukraine, on the front line, to separate the combatants, to make them aware of the infinite abuse to which the leaders expose them. Even at the worst moments of the two world wars, we had observed these moments of solidarity when the soldiers came out of their opposing trenches and fraternized in a spirit that alone could preserve hope. An infinitely fragile gesture, you would say, but one which, I hope despite everything, could put an end to this war whose outcome we are forbidden to imagine.