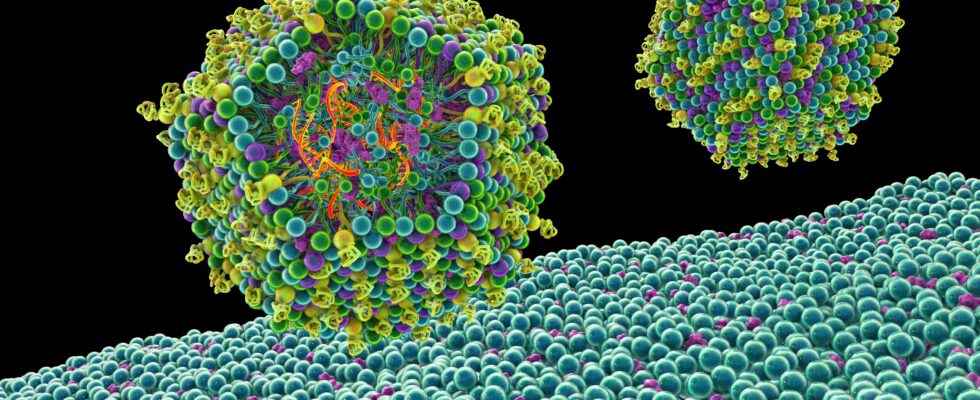

In many ways, they will remain a miracle in the backyard of this global Covid-19 epidemic. Messenger RNA vaccines have been designed, tested, manufactured and brought to market at unprecedented speed. A brief chronological look back in five stages: December 2019, first cases of Sars-CoV-2 detected in Wuhan (China); at the end of January 2020, the firm Moderna took four days to manufacture its vaccine; during March, first trials on humans; December 2020, start of the vaccination campaign in France; December 2022, 140 million doses delivered in France, 90% of adults vaccinated. “The crisis has made vaccination take a technological leap”, notes infectious disease specialist Anne-Claude Crémieux in her book Citizens have the right to know (Fayard). Tomorrow, messenger RNA vaccines could revolutionize the treatment of other infectious diseases (HIV, malaria), or even help to defeat cancer. But the pandemic has also made it possible to advance medicine in many other fields…

Wastewater to better monitor microbes

Summer 2020. The “reassuring” repeat over and over that the pandemic is over. However, a handful of virologists already know that this is not the case. “The virus, excreted by the stools of infected people, had reappeared at the end of June in wastewater, but our alerts remained a dead letter”, recalls Vincent Maréchal, co-founder of the Obépine project (Epidemiological observatory in wastewater) . The second wave will prove his team right, and will confirm the interest of scrutinizing the sewers to follow, or even anticipate, the evolution of the epidemic. Obépine will follow up to 200 stations.

The idea is not new: since the 1930s, sewage treatment plants have served as polio watchdogs. Subsequently, the sewage water will be used to monitor the consumption of antibiotics, birth control pills, or drugs. “But it’s really the Covid that has given a boost to this technique”, underlines Vincent Maréchal. The European Union now recommends that all Member States deploy this surveillance tool. In France, the project was transferred in April 2022 to the Ministries of Health and the Environment, under the name of SUM’eau. Since August, the administration has been monitoring 12 wastewater treatment plants (one in each major region except Corsica). “The system is intended to ramp up from the end of the first quarter of 2023, with a greater number of sites”, assures the Directorate General of Health.

For their part, Obépine scientists have set themselves a new challenge: to create a research platform to fight against emerging infectious diseases. To do this, they will monitor common viruses in our latitudes (influenza, RSV, etc.) and build mathematical models by crossing epidemiological data and signals from wastewater treatment plants. This work will then be applied to the monitoring of farms (avian or swine flu), and above all to preventive monitoring in the face of new threats (dengue fever, polio virus derived from vaccines, mpox, zika, etc.). “We are also developing and validating sampling tools adapted to countries without sewage networks, because epidemiology from wastewater is proving to be very effective and inexpensive”, announces Vincent Maréchal. This technique has not finished making people talk about it.

In intensive care, the revolution in high-flow oxygenation

In intensive care and intensive care units, Covid-19 has also moved the lines, with the generalization of high-flow oxygen therapy. For patients suffering from acute respiratory insufficiency, this method of administering oxygen, which makes it possible to distribute up to 100 liters of the precious gas per minute to the patient (when the low flow represents 2 to 10 liters per minute) has marked a real turning point in the care of patients. “In intensive care it is a significant change in our operating methods”, notes Professor Djillali Annane, head of the intensive care unit at the Raymond-Poincaré hospital (AP-HP) in Garches.

The turning point came at the start of the Covid-19 crisis, when intensive care unit teams, facing a shortage of artificial respirators, turned to these oxygen distributors, which had been little used until then. “This incidentally led to the generalization of high-flow oxygen therapy, which proved to be very effective. And today, it has become routine in intensive care units”, explains Pr. Annane. By avoiding recourse to invasive and dangerous intubation for the patient – in particular because of the risk of infection and placement under general anesthesia – this method of administering oxygen has made it possible to reduce mortality in the care services. intensive, assures the doctor.

Since then, this practice has no longer been reserved for Covid patients alone, but has also been extended to other pathologies which usually required placement on artificial ventilation. “We can really say that there was a before and an after”, underlines Djillali Annane.

Virus sequencing, key to understanding their evolution

Until three years ago, the genetic sequencing of viruses and its analysis – which goes by the name of phylogenetics – were disciplines unknown to the general public. By now everyone has heard of Sars-CoV-2 variants. Many, too, have seen the famous “family trees”, which show how the virus has mutated since the end of 2019, from the original Wuhan strain to the Alpha, Delta variants to Omicron and its sub-variants.

And, if these disciplines remain sharp, many now know that they have helped us to fight against the Covid. It is thanks to them that the investigation into the origin of the virus – still in progress – is possible, that we know when and where a new variant is spreading and that researchers can offer precise models of the epidemic. “We were struck by the interest of the general public in our work and to be called by the media to popularize it. This was very motivating for our entire field”, testifies Samuel Alizon, one of the main French experts in phylodynamics, director of research at the CNRS, in charge of the Ecology and evolution of health team at the Collège de France.

Genetic sequencing has been one of the strengths of France, which has generated numerous sequences and produced a great deal of data from PCR samples. “On the side of phylogenetic analysis, we were weaker, but Great Britain, the United States, or Switzerland have shown the importance of this field, adds the researcher. In France, we have all the same been integrated into research projects, which allowed us to obtain funding… It remains to be seen whether this is a temporary interest or not.”

More efficient tests for better care

If some city doctors continue to rely on their judgment rather than on a Streptotest to know whether or not they should prescribe antibiotics in the event of angina, rapid tests seem to have a bright future. The Covid pandemic has given a big boost to certain practices: antigenic tests, self-tests or multiplex PCR capable, in a few hours, of detecting several pathogens at the same time, or even of identifying resistance genes.

And the future will no doubt give the diagnostics industry the opportunity to go even further. Because, as a recent report drawn up by members of six academies (Medicine, Science, Technology, Agriculture, Veterinary and Pharmacy) reminds us, we can expect, in addition to the appearance of new viruses, to see the emergence of epidemics of bacterial origin due to the development of antibiotic resistance of existing infectious agents. Their mastery will pass, for these experts, through the massive use of tests capable of detecting them in order to administer the treatments wisely. “I hope that we will move towards more rapid tests in the future”, confirms Dr Thierry Naas, bacteriologist at Bicêtre hospital (AP-HP).

However, this rise in power supposes to remove some brakes. The first is industrial: at present, the development of diagnostic tools depends too much on raw materials and foreign know-how. The high price of new techniques also makes their adoption more difficult. “As an example, a multiplex PCR test costs around 100 euros”, confirms Thierry Naas. Whereas it only takes a few cents to cultivate a micro-organism.