Bacterial infections are the second leading cause of death worldwide, after heart disease, according to a very large study published Tuesday, November 22 by The Lancet. In 2019, these were responsible for more than 7.7 million deaths worldwide, that is to say one in eight deaths. For Professor Eric Oswald, head of the bacteriology department at the Toulouse University Hospital, joined by The Express“this study is a reminder that bacterial infections remain an ongoing challenge for medicine, and that we must not slack off in the fight against them”.

These measurements (carried out before the Covid-19 epidemic) were carried out as part of the vast “Global Burden of Disease” program, which can be translated as “Global burden of disease”. Funded by the Bill Gates Foundation, it is of an unparalleled scale, involving several thousand researchers in most countries of the world.

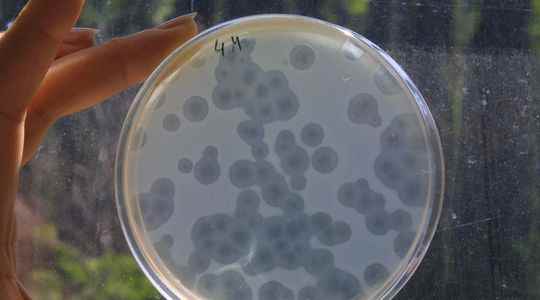

Five bacteria account for half of deaths

The study selected the thirty-three bacteria most often implicated in infections, and assessed how many deaths are associated with them. Five bacteria alone account for more than half of the deaths: Staphylococcus aureus, E. Coli, pneumococcus, Klebsellia pneumoniae and bacillus pyocyanin. More specifically, Staphylococcus aureus is “the leading bacterial cause of death in 135 countries,” the study said. In children under five, pneumococcal infections are the most deadly.

These figures do not take into account deaths from tuberculosis, which is also a bacterial infection and which alone is responsible for nearly 1.4 million deaths each year. according to the Pasteur Institute.

The aging of the population could promote their development

“These results are not a surprise for the scientific community: humanity has always been threatened by infectious diseases. In the 1950s and 1960s, people thought they could eradicate the disease using antibiotics, before becoming Since then, we have relaxed a little, the hygiene of life has improved a lot in the most developed countries, and we sometimes seem to forget that we live in a world surrounded by microbes”, relates the scientist from the Inserm, Eric Oswald.

The study published by The Lancet notably points to important differences between the way in which these bacterial infections affect the poorest and richest regions of the globe. Sub-Saharan Africa thus experienced 230 deaths per 100,000 inhabitants due to bacterial infections over the same period. That number drops to 52 per 100,000 in what the study calls the “high-income super-region” which included countries in Western Europe, North America and Australasia.

But for Eric Oswald, the fight against bacterial infections must also concern the most developed countries. “By gaining in lifespan thanks to medicine, we find ourselves with an aging population in Europe, which is very vulnerable. What we have gained in quality of care, we lose it in the fragility of the elderly population today, he summarizes. However, we know that as was the case for the Covid, bacterial infections are often contracted in addition to a serious pathology in fragile people, they are coupled with comorbidities”, explains the researcher. He also recalls “that we still die today in France of these infections, such as sepsis which claims many victims each year”.

The challenge of bacterial infections is ongoing and global

For researchers from the Global Burden of Disease, the results of this study illustrate once again how bacterial infections are an “urgent priority” in public health. “These new data reveal for the first time the full extent of the global public health challenge posed by bacterial infections,” study co-author Christopher Murray said during his presentation.

A situation that could become more and more severe. On Wednesday, October 23, the Global Fund to Fight AIDS warned of the “escalation of the impact” of climate change on health, predicting that it will contribute to the development of infectious diseases such as tuberculosis and pneumococcus. , but also malaria and AIDS, mainly due to rising temperatures and flooding that allow mosquitoes to thrive.

To combat their development, the researchers call for work on the prevention of infections, better use of antibiotics that are too often unfairly used, as well as instilling additional investments in vaccination. “The approach must be multiple”, confirms Éric Oswald, who recalls that antibiotics or vaccines will not overcome them alone.

“We must improve the quality of diagnosis and care, develop treatments and vaccines as bacteria evolve, but also help the least developed countries to strengthen the hygiene of their lifestyles and their hospital systems, summarizes We must fight on all fronts at the same time, and remember that this will be a long-term job.