By Gilles Pison, National Museum of Natural History (MNHN)

The world population is 8 billion in 2022. It was only 1 billion in 1800 and has therefore increased eightfold since then (see Figure 1 below). It should continue to grow and could reach almost 10 billion in 2050. Why should the growth continue? Is stabilization possible in the long term? Wouldn’t degrowth right away be preferable?

Figure 1. Click to zoom. Gilles Pison (from United Nations data), CC BY-NC-ND

If the world population continues to increase, it is due to the excess of births over deaths – the first are twice as many than the latter. This excess appeared two centuries ago in Europe and North America when mortality began to decline in these regions, marking the beginnings of what scientists call the demographic transition. It then spreads to the rest of the planet, when advances in hygiene and medicine and socio-economic progress reach the other continents.

A growing African population

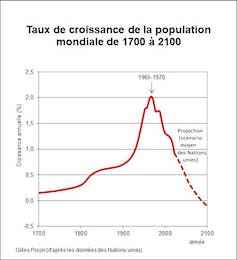

Population growth slows down though. It peaked at over 2% per year sixty years ago and has since halved, reaching 1% in 2022 (see Figure 2 below).

Figure 2. Click to zoom. Gilles Pison (from United Nations data), CC BY-NC-ND

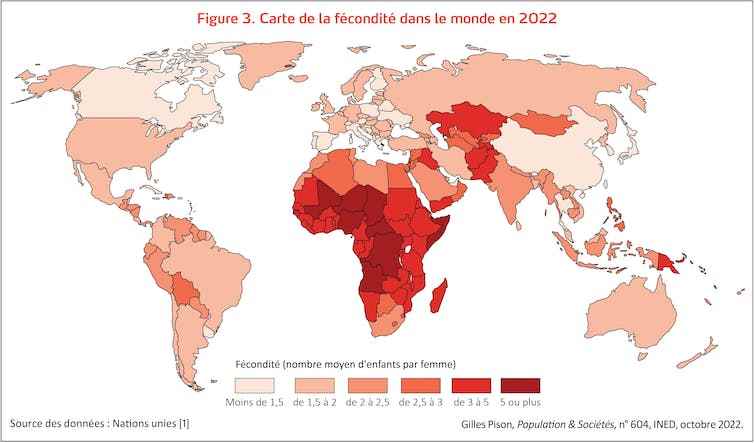

It should continue to fall in the coming decades due to the decline in fertility: 2.3 children on average per woman today in the world, compared to double (five children) in 1950. Among the regions of the world where fertility is still high (greater than 2.5 children), we find in 2022 almost all of Africa, part of the Middle East and a strip in Asia ranging from Kazakhstan to Pakistan via Afghanistan (see the map below). This is where most of the world’s future population growth will be located.

One of the great changes to come is the tremendous growth in the population of Africa which, including North Africa, could triple by the end of the century, rising from 1.4 billion inhabitants in 2022 to probably 2 .5 billion in 2050. While one in six humans live in Africa today, it will probably be more than one in three in a century. The increase should be particularly significant in Africa south of the Sahara where the population would increase from 1.2 billion inhabitants in 2022 to 3.4 billion in 2100 according to the medium scenario of the United Nations.

Map of fertility in the world in 2022. Click to zoom. Ined, Supplied by the author.

What to expect in the coming decades

These figures are projections and the future is obviously not written.

It remains that demographic projections are relatively reliable when it comes to announcing the size of the population in the short term; that is to say for a demographer, the next ten, twenty or thirty years. The majority of men and women who will live in 2050 have already been born, we know their number and we can estimate without too much error the proportion of humans today who will no longer be alive. Concerning the newborns who will be added, their number can also be estimated, because the women who will give birth to children in the next 20 years have already been born, we know their number and we can also make an assumption on their number. of children, again without too many errors.

It is illusory to think of being able to act on the number of men in the short term. Decreasing the population is not an option. Because how to get it? By an increase in mortality? Nobody wants it. By massive emigration to the planet Mars? Unrealistic. By a drastic drop in fertility and its maintenance at a level well below replacement level (2.1 children) for a long time. This is already happening in a large part of the world, humans having chosen to have few children while ensuring them a long and quality life.

But this does not immediately result in a decrease in population due to demographic inertia: even if world fertility was only 1.5 children per woman right away like in europe, the population would continue to increase for a few more decades. The latter still includes many adults of childbearing age, born when fertility was still high, resulting in a high number of births. On the other hand, the elderly or very elderly are few in number on a global scale and the number of deaths is low.

The issue of declining fertility

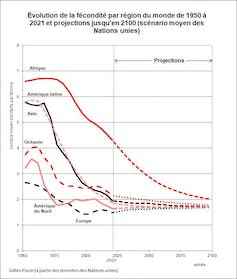

Demographers were surprised forty years ago when surveys revealed that fertility had begun to decline very rapidly in many Asian and Latin American countries in the 1960s and 1970s. lowering their demographic projection for these continents.

Another, more recent surprise came from Africa. Its fertility was expected to decline later than in Asia and Latin America, in relation to its lag in socio-economic development. But we imagined a simple shift in time, with a rate of decline similar to other regions of the South once this one started. This is indeed what happened in North Africa and Southern Africa, but not in intertropical Africa where the decline in fertility, although begun today, is taking place there. slower. Hence an increase in projections for Africa, which could contain more than one inhabitant of the planet in three in 2100.

Fertility is decreasing in intertropical Africa, but in educated circles and in towns more than in the countryside where the majority of the population still lives. If the decline in fertility there is currently slower than that observed a few decades ago in Asia and Latin America (see Figure 4 below), this is not due to a refusal of contraception.

Figure 4. Click to zoom. Gilles Pison (based on United Nations data), CC BY-NC-ND

Most rural families have certainly not yet converted to the two-child model, but they would like to have fewer children and in particular more widely spaced. They are ready to use contraception for this purpose but do not benefit from appropriate services to achieve this. National birth control programs exist but are inefficient, lack the resources, and above all suffer from a lack of motivation on the part of their managers and the staff responsible for implementing them in the field. Many are not convinced of the interest of limiting births including at the highest state leveleven if it is not the official discourse given to international organisations.

This is one of the differences with Asia and Latin America in the 1960s and 1970s and one of the obstacles to be overcome if we want fertility to decline more rapidly in sub-Saharan Africa.

In the long term: explosion, implosion or equilibrium?

Beyond the next fifty years, however, the future is full of questions, with no model on which to rely.

That of the demographic transition, which has proven its worth for the evolutions of the last two centuries, is of little use to us for the future. One of the great uncertainties concerns fertility. If the very small family becomes a dominant model in a lasting way, with an average fertility of less than two children per woman, the world population, after having reached the maximum level of ten billion inhabitants, would decrease inexorably until eventual extinction.

But another scenario is possible in which fertility would rise in countries where it is very low to stabilize on a global scale above two children. The consequence would be uninterrupted growth, and again the eventual disappearance of the species, but this time by excess. If we do not resolve the catastrophic scenarios of the end of humanity, by implosion or explosion, we must imagine a scenario of a return to equilibrium in the long term.

It’s the lifestyles that matter

Humans must of course now think about the balance to be found in the long term, but the urgency is the short term, that is to say the next few decades.

Humanity will not escape an increase of 2 billion inhabitants by 2050, due to the demographic inertia that no one can prevent. On the other hand, it is possible to act on lifestyles, and this without delay, in order to make them more respectful of the environment and more economical in resources. The real question, the one on which the long-term survival of the human species depends, is ultimately less that of numbers than that of lifestyles.

Find Gilles Pison in the podcast of the National Museum of Natural History “So that nature lives”with the episode “Are there too many of us on Earth? ».![]()

Gilles PisonAnthropologist and demographer, professor at the National Museum of Natural History and associate researcher at INED, National Museum of Natural History (MNHN)

This article is republished from The Conversation under Creative Commons license. Read theoriginal article.

![]()