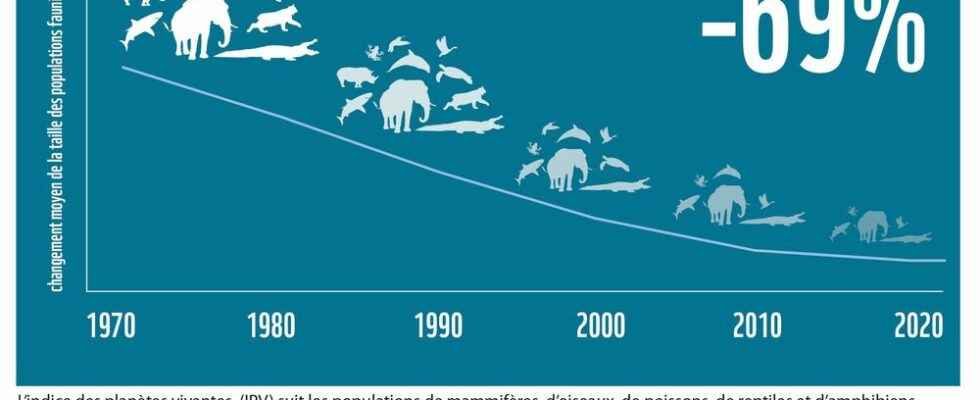

The figure is chilling: the planet has lost an average of nearly 70% of its wild animal populations in about fifty years. At first glance, this observation drawn from the Living Planet Index – the benchmark assessment of the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) – published on Thursday, October 13 leaves little hope. Without concerted and global action, biodiversity will have disappeared from our dear Earth within a few decades at most. However, if it has the merit of alerting the population and those in power to the urgency of acting, this figure should be put into perspective.

First, as staggering as they are, these famous 69% – to be precise – only concern wild vertebrates: birds, fish, mammals, amphibians and reptiles. Living beings without backbones and bones, such as insects, jellyfish, sponges or certain planktons are absent. However, these populations represent the vast majority of animal species. Nothing unusual about that. Invertebrates, which are often small and live out of sight, are more difficult to study and therefore to count.

However, invertebrates, and in particular insects, are also threatened with extinction. According to a meta-analysis of 73 different studies on the state of entomological fauna published in 2019 in the journal Biological Conservationmore than 30% of insect species are threatened with extinction, which would represent the “most massive extinction episode” since the disappearance of the dinosaurs. Worse, it seems probable, even if the estimates vary according to the studies, that the population of insects has decreased by 75% in fifty years. Hymenoptera, such as bees or ants, see their populations threatened with extinction by more than 50%. If invasive species take advantage of this to take their place, such as the feverish bumblebee or the fire ant, which tolerate pesticides better than their congeners, their growth is not rapid enough to compensate for the disappearance of other species. According to some specialists, in 100 years, all insects could have disappeared from the surface of our planet…

Collapse of vertebrates since 1970.

@WWF

However, the disappearance of these animals could cause cascading disasters. First, those that feed on insects (birds, amphibians, fish or bats) would be deprived of food. Some studies have already shown a direct link between the decline of certain vertebrates and the decline of insects. Then, it would have an impact on pollination, which would have serious consequences for our agriculture, as we prepare to cross the threshold of 8 billion human beings. Ultimately, the collapse of insects would drag down biodiversity as a whole, and directly threaten humanity.

A “catastrophic” reality

But back to our dear vertebrates. Did their population drop by 69% as this report might suggest? The answer is no. The study, conducted by the Institute of Zoology in London, tracks 5,320 species, spread across some 32,000 animal populations around the world. And the report makes it clear that this figure must be put into perspective. Imagine, write the authors, that we start from three populations: birds, bears and sharks. Birds drop from 25 to 5, a drop of 80%. Bears that were 50, drop to 45, a 10% drop. And the sharks drop from 20 to 8, a drop of 60%. This gives us an average drop of 50%. But the total number of animals fell from 150 to 92, a drop of around 39%. At the end of 2020, researchers had judged, in an article published in Science, that this indicator gave a “catastrophic” view of the erosion of biodiversity, estimating that the extreme decrease in certain populations affected “disproportionately” the global average. .

For this new edition, the index has been recalculated by excluding certain species or populations, and integrating 838 new species and 11,011 more populations compared to 2020 – a considerable increase. “Even after removing 10% of the full data set, we still see drops of around 65%,” said Robin Freeman, head of the Zoological Society of London’s indicators and assessments unit and author. of the report.

However, let’s not get sidetracked. The report points to an undeniable reality: the living is in the grip of a mass disappearance, probably underestimated. In just fifty years, lowland gorilla populations have declined by 80%; those of African forest elephants, classified as critically endangered, by 86%. Populations of oceanic sharks and rays have also collapsed (-71%). Other populations – about half of those studied – are stable or increasing. The figures are “really frightening” for Latin America, said Mark Wright, scientific director of the WWF, with 94% disappearance on average in this region “renowned for its biodiversity” and “decisive for climate regulation”. Europe has seen its population of wild animals decrease by 18% on average. The destruction of natural habitats, especially to develop agriculture, remains the main cause, according to the report, followed by overexploitation and poaching. Climate change is the third factor, but its role is “increasing very, very fast”. This is followed by air, water and soil pollution, as well as the dissemination by man of invasive species.

On the eve of the COP15 Biodiversity to be held at the beginning of December, governments have been warned. They will have to establish a new global framework aimed at halting the collapse observed by the end of the decade. Otherwise humanity will have, in the near future, to face up to its faults, and assume that it has not done anything in time. Because if the situation is catastrophic, it is not yet hopeless.