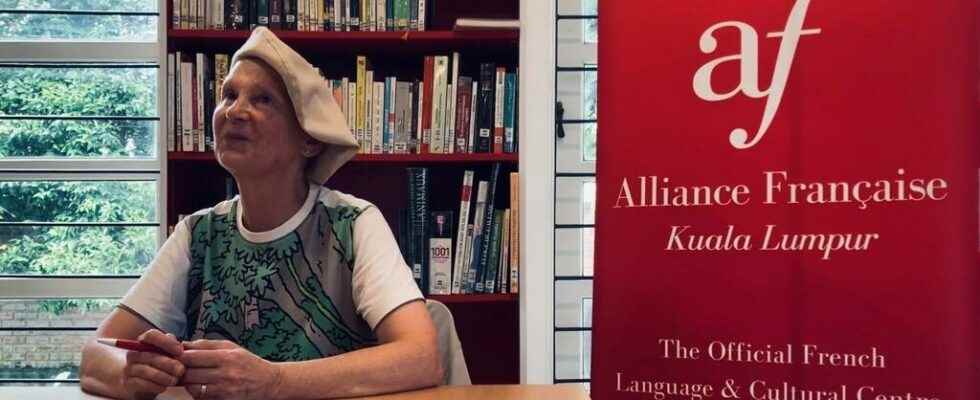

With millions of copies sold and nearly a hundred books published, French author Marie-Aude Murail has been a leading figure in world children’s literature for decades. His work has now just been awarded the Andersen Prize – often dubbed the Nobel Prize for children’s literature – on the occasion of the thirty-eighth edition of the prize, organized by the International Union for Children’s Books, in Putrajaya, administrative capital of the country.

From our special correspondent in Putrajaya, Gabrielle Marshals

If Marie-Aude Murail says she is overjoyed to have received the Andersen Prize, she nevertheless knows that the child reader who reads her does not have much to do with this kind of honor.

” He is a reader who does not want to be bored in fact, and who does not give you any credit. I mean that it is not because I have the Andersen Prize that people will read me, whereas if I had the Goncourt Prize, there are adults who would agree to be bored while reading me. The children no, they will plant me. Afterwards, I have this reader who grows up and becomes a teenager, and at that time, his requirement is that I make him discover the world, and that I open all the doors to him, including that of his heart. . »

The child appropriates the book

And when she succeeds, the children’s author knows that she can sometimes have a considerable impact on her reader. “The child reads and rereads, he appropriates the book. And it will mark him for life. Me, I forget the book I read last week, but my Tintins, never, because I read them 36 times! And so we know that we are going to be important. And that I know now because these teenagers have become adults, they write to me. I have a very recent memory of a young girl who came to tell me that after reading “Vive la République”, one of my books, she became an alter-globalist and a vegetarian. And after reading “Oh Boy”, she decided to study medicine. »

Censorship threat

But if children’s books hold great power, they are also the object of a lot of attention and regularly threatened with censorship, worries Marie-Aude Murail, who thus chose this topic of discussion for the plenary session of the International Union for Children’s Books, held on the sidelines of the Andersen Prize. “ In France, we don’t know much about it, but children’s literature is still subject to a 1949 law, a period when people were worried about the arrival of American comics, she reports. This law says that we must not write things that would push young people to violence, that we must not “demoralize “young people”.

Today, the author is concerned about the growing use of petitions and statements aimed at banning certain children’s books. A climate which, she says,“frightens publishers”. ” The risk, she continues, is that children’s literature will only be literature that will not make waves, that will not deal with any controversial subject. »

Translated into more than twenty-seven languages, Marie-Aude Murail has already seen some of these censored books when crossing borders: “In Russia, a recent law stipulates that young people are not allowed to talk about “non-traditional way of loving each other”. My book “Oh Boy”, where a character is homosexual, was thus withdrawn from a collection for teenagers, where it had been published for years, to be today a book in a adult collection. Societal themes subject to debate such as religion, the discovery of sexuality, global warming, dysfunctional families. The prolific work of Marie-Aude Murail nevertheless abounds in it and when asked if it is possible to find a common thread in all this variety, the author’s response bursts out: “I give characters to love, and we do everything to save them. »