The statement will undoubtedly date. More than ten years after the Fukushima disaster and as the energy price crisis rages, Japan intends to accelerate its return to the world nuclear scene. In any case, this is the meaning of the statements made on Wednesday August 24 by Prime Minister Fumio Kishida, who undertook to relaunch as much as possible the reactors that have been closed since the 2011 disaster and which have been given a regulatory green light. Faced with the current energy crisis, and to counter “potential crisis scenarios in the future”, the head of government also said that he was thinking about the development of “new generation reactors”.

Two decisions, which the head of the Japanese government justifies by the “transformation of the world energy landscape” since “the Russian invasion of Ukraine”. Like other countries, Japan has suffered the brunt of the fossil fuel crisis since the beginning of the conflict. According to the International Energy Agency (EIA), fossil fuels accounted for 88% of Japanese energy consumption in 2019. Problem: it is precisely these that have been affected in recent months. Difficulty of supply, international competition for the purchase of materials between Europeans and Asians lead to soaring prices. The example of liquefied natural gas, of which Japan is the world’s leading importer, is enlightening. In the space of a year, the price of the Japan/Korea Marker, the benchmark index on this market, has tripled, rising from 18 dollars/MBtu in August 2021 to 56 dollars/MBtu.

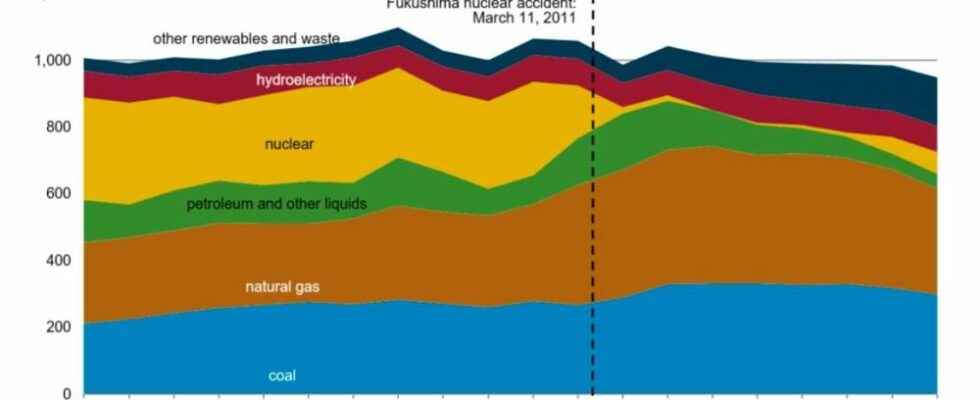

By doing without a large part of its fleet in 2011 – less than 5% of the electricity generated in Japan came from the 54 nuclear reactors in 2020, against 30% before the disaster at the Fukushima power plant – the archipelago s is placed in a situation of ultra-dependence on imports of fossil fuels. The share of natural gas and coal in electricity production has increased considerably and Japan monopolizes the fourth place in the world for importers of black gold.

The share of nuclear has fallen sharply in Japan’s energy mix since 2011, in favor of fossil fuels.

Energy Information Administration

Nuclear again unavoidable

A vulnerability accentuated by its geographical location. As an archipelago with no pipeline with producing countries or interconnection with its neighboring countries, Japan is fully exposed to the soaring costs of global maritime transport, which is added to that of fossil fuels. Also, despite the convincing results of the major energy consumption reduction plan adopted in 2011 – Setsuden – and a strong desire to boost the weight of renewable energies – which represented just under 10% of the energy mix in 2019 -, the recourse to nuclear power is affirmed as essential in the eyes of the Japanese executive.

The decision looks like a turning point, but in reality, the weak signals were multiplying. In an opinion poll relayed by Bloomberg last April just after the start of the conflict, a majority of Japanese (53%) said they were in favor of restarting nuclear reactors, a first in eleven years. The situation worsened during the summer, when the archipelago was threatened by electricity shortages in the middle of a heat wave, due in particular to the use of air conditioning at full speed.

In fact, Japan has nuclear capacity, so to speak, in reserve. Of the 54 reactors that the country once had, 33 units are considered operable by the regulatory authorities, but only ten have actually been put back into service since their shutdown in 2011. Three units are currently shut down for maintenance.

Climate emergency

In addition to the issue of prices and security of supply, nuclear power also appears to be an asset in the country’s environmental strategy. Japan has set itself specific objectives, aiming for carbon neutrality by 2050, like the Member States of the European Union. In this regard, the Japanese government believes that nuclear energy – carbon-free energy – can be part of the solution. A thesis supported by analysts. According to the International Energy Agency, the country’s CO2 emissions peaked in 2013 before falling “thanks to the development of renewable energies, the restarting of some nuclear reactors and improvements in energy efficiency”.

For its part, the Japanese Agency for Natural Resources and Energy (ANRE) demonstrated in 2018 that the drop in CO2 emissions is due to the increased use of renewables and the gradual restart of nuclear power plants. That year, two of them resumed production as part of a “fifth strategic energy plan” to boost nuclear production by 2030. The objective: to reduce hydrocarbon imports and strengthen the country’s energy security.

With regard to hydrocarbon imports, the benefit will be immediate because the work is enormous. In 2019, another 45% of the country’s CO2 emissions were linked to the electricity production and heating sector.

Greenhouse gas emissions by sector. In 2019, in Japan, about 45% of CO2 emissions were related to electricity production and heating.

Climate Analysis Indicators Tool