The monkeypox virus, which has been mostly seen in Africa for 50 years, started to spread around the world in May.

Scientists investigating ways to combat the virus have taken advantage of two smallpox vaccines that have been used in the past: ACAM2000 and JYNNEOS.

Only these two vaccines are allowed in the United States to protect against monkeypox. The European Union has also approved the use of JYNNEOS.

Both vaccines are considered to be extremely safe and effective. But the history of these vaccines is also part of a great mystery.

For more than 100 years, the scientific community believed that the smallpox vaccine was derived from cowpox.

But in 1939, about 150 years after the development of the smallpox vaccine, molecular tests revealed that this was not the case.

More recent genetic sequencing confirmed these findings.

Accordingly, the vaccines that brought the end of smallpox and are used today against monkeypox are based on an unknown virus that no one has been able to diagnose until now.

Despite 83 years of research, no one knows how, why or when this virus was introduced into the smallpox vaccine, or whether it still exists in the wild.

Only one thing is known: Millions of people who lived in the years when smallpox challenged people’s lives owe their lives to this virus.

In addition, without this virus, the monkeypox virus would now be spreading at a much faster rate.

“Until 1939, smallpox vaccine was thought to be identical to cowpox virus for a very long time,” said virologist Jose Esparza of the Robert Koch Institute in Germany. However, it was later found that they contained different viruses. “Since then, we have considered the cowpox virus a type of vaccinia, and the smallpox vaccine as another species of unknown origin.”

So how is this possible? Where did this virus come from? Is it possible that we will one day be able to determine where its natural environment is?

‘Just an accident’

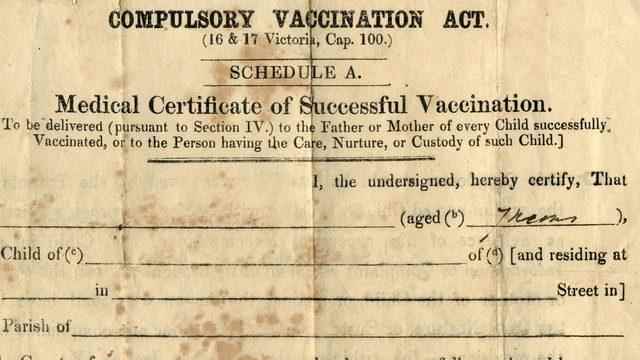

Although hundreds of years have passed since the smallpox vaccine was first made, it is possible to see traces of ancient viruses in museums or collections around the world.

An international team led by Esperza found a vaccine produced in Philadelphia in 1902 during an excavation in 2017.

No trace of cowpox virus was found in the tests. Instead, it was concluded that there was a kinship with the horsepox virus, which was detected in Mongolia in 1976.

Since then, the same team has found and sequenced numerous other historic vaccine samples. “We did not find cowpox in any of the 31 samples,” Esperza says.

So in the 19th and 20th centuries, vaccines were mostly derived from horsepox. The bovine flower was either not used at all or was soon compensated by the horse flower.

But when the scientists sequenced more smallpox vaccines, they found that they also underwent a transformation.

These vaccines were not only predominantly horsepox, but actually a mysterious virus, which is still in vaccines today.

“Until 1930, the main sequence was horsepox, then it evolved into vaccinia, the smallpox vaccine, but we don’t know the origin of it,” Esparza says.

According to Esparza, the sudden jump from one type of smallpox to another has to do with how the vaccine is made:

“For the first 100 years of vaccination history, there were vaccinations from one person’s arm to the other’s arm. In 1860, scientists in Italy and France developed the animal vaccination system. Thus, instead of transmitting the virus from person to person, the method of putting it in cattle and keeping it there was developed.”

With this mass production system, other animals such as sheep, horses and donkeys were included in the chain after a while.

At one point, a virus contained in an unknown animal began to be used as a smallpox vaccine. There is no record of who first did this, or why, how or why such a thing happened.

Maybe it was just an accident: Maybe someone used a virus from a farm animal that they thought was horse or cowpox, the virus worked, and no one realized it was a different kind of virus.

The cause of the epidemic is the abandonment of the smallpox vaccine.

In the 1930s, this mysterious virus became the most widely used vaccine. By the middle of the 20th century, hundreds of different types of this virus were encountered throughout the world.

Today, this mysterious virus works better than it has ever been.

Monkeypox virus was first detected in 1970, and until recently, the virus was only found on the African continent.

However, in May 2022, it began to spread around the world at an unprecedented rate. To cut this pace, many countries have ordered millions of doses of vaccine.

The JYNNEOS and ACAM2000 vaccines were both developed from the same mysterious virus that was active in the smallpox vaccine in the 1930s.

In July 2022, the US government ordered seven million doses of both vaccines.

The funny thing is, maybe the only reason we’re dealing with a monkeypox epidemic today is because we’ve abandoned the practice of smallpox vaccination.

Because other viruses are thought to take advantage of this opportunity. Although cattle pox is not very common in cattle, it is seen as an epidemic in rodents around the world, for example.

There has also been an increase in the incidence of the disease in children since the cessation of smallpox vaccination in the 1970s.

Today, people can catch cowpox by rats or cats. Infections are usually mild, with lesions on the face and hands. However, there is no data that this virus is transmitted from person to person.

However, there have been deaths due to this virus. As with monkeypox, the increase in cases is thought to be related to the discontinuation of smallpox vaccination. Some scientists even say cowpox is an imminent health threat.

So there is still a lot of demand for vaccinia. But is it possible for us to one day find out what the origin of this favorite vaccine in human history is?

Esparza is skeptical of this:

“Right now we have more questions than answers.”