How to tell the horror? On Wednesday June 8, an ephemeral exhibition devoted to the Russian massacres in the Ukrainian town of Boutcha, at the Goethe Institute in Paris, gave rise to scenes of intense emotion. Former inhabitants of the devastated city testify to what they experienced, in front of a few photos placed on easels.

The interpreter struggles to follow them, his voice quavers from repeating the horror of the corpses, the fire and the exploded cars. Despite the trauma, survivors talk about life and the future. They want to rebuild a city “where children can run next to a memorial”. A woman speaks, holding her little girl by the hand. Beside them, a stroller and a battered doll they brought from Ukraine.

Resistance

The terrible words of the survivors of Boutcha soon mingle with the romantic notes of an accordion. The Ukrainians present know the song by heart: “Don’t bend, red viburnum, because you have white flowers…” For Sergeï Popov, a musician from the martyred city, singing helps to keep the faith: “without music, there is no more people.” In his eyes, all Ukrainians are potential resistance fighters: those who stayed, those who left, those who fled and those who bear witness.

Wednesday evening, the heart of Europe beats. In the audience, someone evokes the spirit of European solidarity. Not a word, however, on the caution of Olaf Scholz or on the recent statement by Emmanuel Macron, who calls on Westerners not to “humiliate” Russia. The sentence sparked diplomatic tensions between kyiv and Paris. A Ukrainian delegation, including the Deputy Prime Minister and the Speaker of the Ukrainian Parliament, was also present the day before to reiterate the Ukrainian positions.

“Let the heroes live,” replied in a deep voice the Ukrainians present at the rally.

The Express

“Forgive Us”

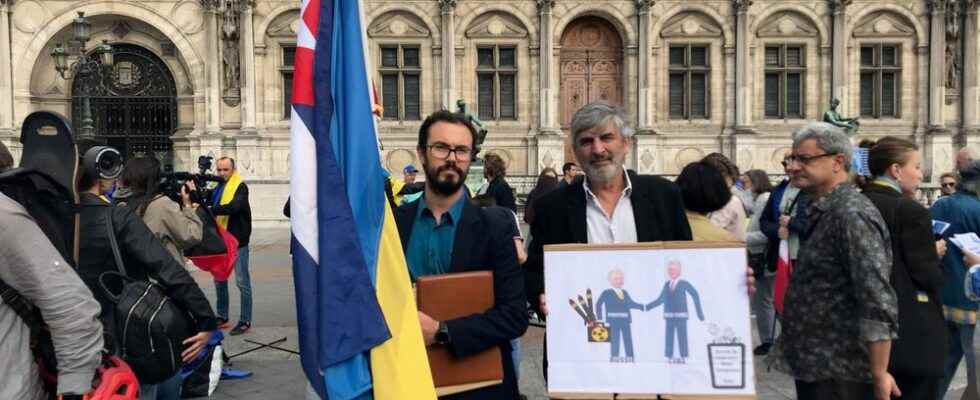

Around 6 p.m., a rally in support of Ukraine takes place in front of the Town Hall. Yellow and blue flags flutter in the strong wind. The mayors of Boutcha and Irpin, another city devastated by the fighting, stand alongside the Ukrainian ambassador, Vadym Omelchenko, but we must also listen to the spectators. One of them demands the entry of Ukraine into the European Union, another shouts Slava Oukraïneither (Glory to Ukraine) and recalls that the war did not start on February 24 and that the first deaths date from 2014. A Russian dissident speaks and lets her tears flow: “Forgive us”. Syrian and Cuban opponents explain to anyone who will listen that the fight against Bashar al Assad, Miguel Diaz Canel or Vladimir Poutine is part of the same fight, that of freedom.

“How Heroes Live”

The demonstration takes an even more political turn when Geneviève Garrigos, elected mayor of Paris, challenges President Macron. “How can we talk about humiliation? Even if your neighbor humiliates you, do you enter his house to rape, burn and kill?” Anger is rising, his words are unequivocal: it is Europe that is humiliating itself by closing the door on kyiv. The crowd applauds. Ukraine’s candidacy may be officially supported by France, but things are not moving fast enough to appease the demonstrators, tired of the timorous attitude of the Franco-German couple towards Vladimir Putin.

Someone then throws one last Slava Oukraïneither. In a deep voice, the Ukrainians answer Heroiam Slava, “How heroes live”. And pray that their soldiers will finally receive the heavy weapons promised to oppose the Russian oppressor.