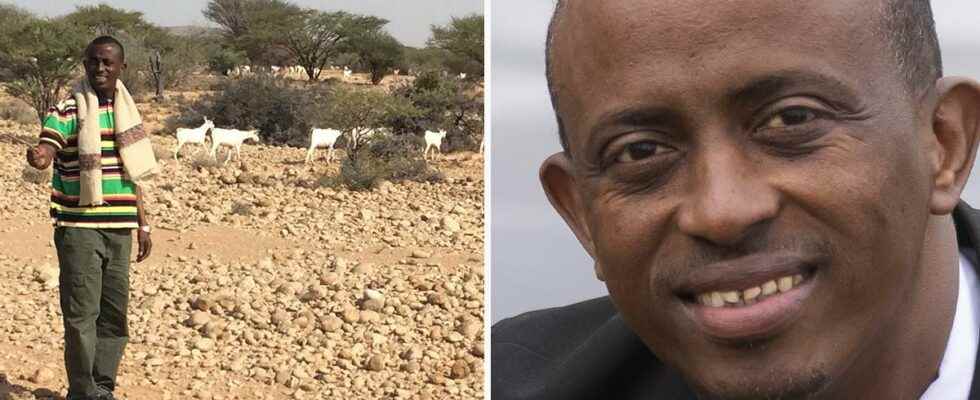

Mursal fled to Sweden from Somalia due to the lack of water.

Now, 20 years later, he is fighting to change the situation in his home country.

– There are about 730,000 people living in the region and 150,000 of them do not have access to water, he says.

Mursal Isa, 41, is a local politician for the Green Party and a member of the Lions. He is also the initiator of the non-profit project “Water means life” which supplies clean water to the Bari region of Somalia. It is an area located at the far end of the Horn of Africa that is extremely affected by climate change and drought and where many people today are dependent on the efforts of aid organizations.

– Water is life-saving for the people of the Bari region. The people there were completely shocked when they saw crystal clear, running water for the first time, says Mursal.

Water means life drills hundreds of meters into the ground to find groundwater. A pump powered by a generator is inserted into the hole and drives the water up into a 15 meter high water tower.

– A borehole can provide water to up to 20,000 people for 60 years, says Mursal.

“We had a fear every day”

He himself was born and raised in northeastern Somalia, where he lived as a nomad on the steppe with his family.

He has experienced the drought and knows how life is affected by water shortages.

– We had a fear every day all year round that the rainwater would run out. When the water ran out in one place, we had to travel far to find water. It is not possible to establish a normal life when you are constantly traveling, he says.

Due to the drought, Mursal left the region. Civil war caused him to leave the country as well.

At the age of 23, he came to Sweden alone.

– I consider myself both a climate and war refugee, says Mursal.

Rested on vacation

The start of the project was in 2008. Then he told his colleagues at the study association ABF in Borlänge about his life. His boss was touched by the words and thought that Mursal would return to the place where he grew up and document the lives of the locals.

– One summer I took a camera with me and went there, he says.

Once back home in Dalarna, Mursal started lecturing about his upbringing and the water situation in the Bari region. One association that was visited was Lions Borlänge, whose chairman Lennart Petterson wanted to get involved in doing something about it.

Money began to be collected.

In the same vein, a group of students at Dalarna University also made a documentary of Mursal’s collected material. The same students also did an analysis of what the people in the Bari region need most and came to the conclusion that it was water.

– In 2011 we were able to hire a Swedish geologist who went down to Somalia with me. The geologist visited villages and towns and investigated where there was groundwater somewhere, says Mursal.

320 meters into the ground

Lions Borlänge applied for Water means life to be a project for the whole of Lions Sweden. In 2018, the application was approved, after which the collection of money took off in earnest.

The following year, the project also received funding from International Lions as the association is present in several countries around the world.

– We found a drilling company in northeastern Africa that could take the assignment. In September 2019, we started drilling where the geologist said that groundwater would be available. 320 meters into the ground we found water.

Third hole in progress

Barely two years later, water hole number two was drilled up to 70 km from the first hole. This summer, hole number three will start ten miles from the previous one. Then Mursal, like the two previous times, will be in place to start up.

– Our goal is to drill five water holes. But it’s a drop in the ocean. There are about 730,000 people living in the region and 150,000 of them do not have access to water. In the best of worlds, there should be a hole every forty miles, says Mursal.

He believes that only when there is water available will it be possible to talk about other things in the region. For example, democracy, gender equality and education.

– People without water are not receptive to taking in information. They only ask for water, says Mursal Isa.