You will also be interested

[EN VIDÉO] The Sunray Illusion Never look the Sun straight in the eye.

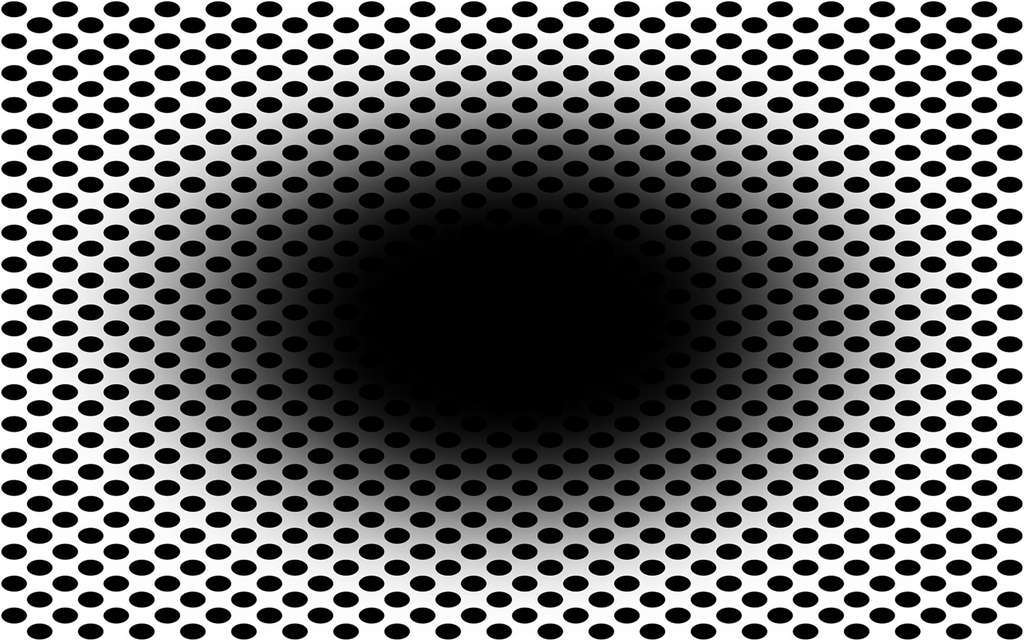

The optical illusions are not just funny. Not even just confusing. They are also used by researchers to better understand how our brain makes sense of the world around us. And precisely, a Oslo university team (Norway) today reveals an optical illusion capable of tricking our brains to the point of triggering a reflex. Facing “expanding hole”, the pupils of 86% of us dilate exactly as they would if we walked into a dark area. The illusion that the image gives.

For the researchers, the experiment shows that our brain actually reacts to the way we perceive the light. Even if this light is “imaginary”. As is the case with this optical illusion. Our brain does not react only according to the amount of light that actually enters our eye.

Different perceptions

What the researchers also report, after studying the responses to this optical illusion of 50 women and men, is a difference in reaction between a “expanding hole” black and one “expanding hole” colored. The appearance of colors, in effect, seems to diminish the potency of the perceived optical illusion. But also, modify the reflex response. In our eyespupils which tend to dilate strongly – and all the more when the volunteers strongly express their perception of the illusion – in the presence of a “expanding hole” black and to contract in the presence of a “expanding hole” colored.

At this point, researchers don’t know why some people seem oblivious to this optical illusion. They also don’t know ifother animals might be sensitive to it. But the whole thing shows that the dilation reflex of our pupils cannot be compared to the mechanism of a cell photoelectric operating a gate and which only reacts to the actual amount of light that hits it.

The psychedelic tendrils of Akiyoshi Kitaoka Keeping the gaze fixed on the central zone, the twisted patterns come to life. A bit dizzying… © Akiyoshi Kitaoka, DR

Akiyoshi Kitaoka’s Spinning Flowers Looking closely, these circular figures begin to turn, like gears. This illusion which deceives the analysis of movement is due to the Japanese Akiyoshi Kitaoka, professor of the department of psychology of the university Ritsumeikan, in Kyoto. © Akiyoshi Kitaoka, DR

Akiyoshi Kitaoka’s Undulating Squares They are just squares. Yet they seem to form ripples. Better, these waves sometimes seem to start moving, especially if you move the image on the screen a little. © Akiyoshi Kitaoka, DR

Trompe l’oeil by Akiyoshi Kitaoka Almost a trompe-l’oeil, this plan drawing becomes hollow, evoking a well or a bottomless tube. © Akiyoshi Kitaoka, DR

Akiyoshi Kitaoka’s Spinning Serpents You have certainly already come across these snakes; they are the work of the Japanese Akiyoshi Kitaoka. They are materialized by a multitude of circles, themselves composed of concentric circles. When we scan this assemblage, they come to life through repetition and concentricity. © Akiyoshi Kitaoka, DR

Adelson’s chessboard and its green cylinder In 1995, Ted Adelson published his chessboard. Two squares A and B, although of the same color, seem different to us. Our eye is deceived by the shadow cast by the green cylinder and the dark boxes around box B (or the light boxes next to box A). It automatically rectifies and brightens B. Admit that even knowing this, you have a hard time believing us!

The impossible Penrose triangle This impossible object was designed by Roger Penrose in the 1950s. Despite numerous attempts at making it in 3D, this triangle, designed from square section bars crossing each other perpendicularly, can only exist in two dimensions. Some animations demonstrate by breaking the triangle the impossibility of its concrete realization in 3D. © Tobias R., Wikimedia Commons, CC by-sa 2.5

Penrose’s Endless Staircase At the Penroses, we are passionate about optical illusions. When Roger Penrose draws the triangle, his son Lionel takes over and imagines an equally impossible staircase. On the other hand, on paper, the staircase at right angles seems to go up to infinity in a loop where top and bottom meet. © DP

Necker’s cube and cavalier perspective All the ambiguity of the Necker cube rests on the cavalier perspective. We recognize all the drawings of the cube whose edges are parallel. The relief is suggested there. But, on closer inspection, is it so obvious? At the intersection of the lines, two interpretations are possible for Man and the eye cannot distinguish between things. © GNU

Escher’s paradoxical perspective Widely used by Escher in his work, paradoxical perspective is a graphic art. She relies on optical illusions to build forms, landscapes or improbable constructions. This figure, for example, refutes any law of logic, your project manager would tear his hair out! © Roby, GFDL

The blivet, an impossible object This three-legged object has, at its base, only two rectangular ramifications. The two middle lines connected in a circle have no tangible physical existence. Published in 1965 on the cover of Mad magazine, he established his fame as an impossible figure. © DP

Hering’s illusion and distortion Are the red lines parallel? Nope ? Look better. By an angle effect, the blue lines in the background give an impression of expansion. But take your ruler, they are straight! © Fibonacci, GNU FDL

The Orbison Illusion and the Corner Effect Like Hering, Orbison showed in 1939 that the angle effect of a figure deceives our brain. The arrows tell us that there is perspective, and the square looks distorted. Once again, this is only an illusion; ignore the blue and you’ll see a nice square with four perpendicular corners. © Mysid, DP

The Delboeuf illusion and its concentric circles Which of these two circles is larger? The left one ? Lost, they both have the same diameter! This illusion plays with our perception of size and the circled circle appears larger to us. An optical illusion very close to that of Ebbinghaus. © Famousdog, Wikipedia, CC by 3.0

The Ebbinghaus illusion or the Titchener circles The two orange circles have the same diameter. However, the one on the right seems larger. What’s the cause ? Recent studies suggest that this Ebbinghaus illusion, also called “Titchener circles” (from the name of the book that made them famous, The Titchener circles), is based on the distance between the circles: the closer they are to the central circle, the larger the latter appears. In other words, the brain reconstitutes an imaginary disc around the closest circles. If they are too far apart, as in the figure on the left, the central circle appears as independent, and therefore smaller. © DP

The Ouchi Illusion and Motion Perception This illusion is very impressive and plays with the perception of movement. The same pattern is repeated twice: vertically and horizontally. Placed in the background, it remains motionless. When we superimpose a circle with this same pattern but arranged horizontally, then the inside of the circle seems to move. Yet the image is static. © Ouchi

Rotating circles, an illusion of rotation What do you see ? Two circles. Now stare at the black dot, move away and approach. They move in the opposite direction! This effect is due to the relief of the trapezoids that make up the circle, because their vectors do not have the same direction. © Fibonacci, CC by-sa 3.0

The Cafe Wall Illusion, as described by Richard Gregory It was on the wall of a terrace in Bristol, England, that Richard Gregory noticed a curious effect: the earthenware, whose black and white tiles are interspersed, has curves. Curious thing, since all tiles are, by definition, square. Moreover, the lines, parallel, seem to want to meet. Doctor Gregory was so taken aback that he decided to write about it in an issue of the magazine Perception. © Fibonacci, CC by-sa 3.0

The Ames room and its trapeze This room is quite special. In the shape of a trapeze, it gives the illusion of being cubic if one places oneself at a precise point. This is when two people placed at the same height seem to have two different sizes. Practical, this effect is used in the cinema. © Mosso, CC by-sa 2.0

Interested in what you just read?