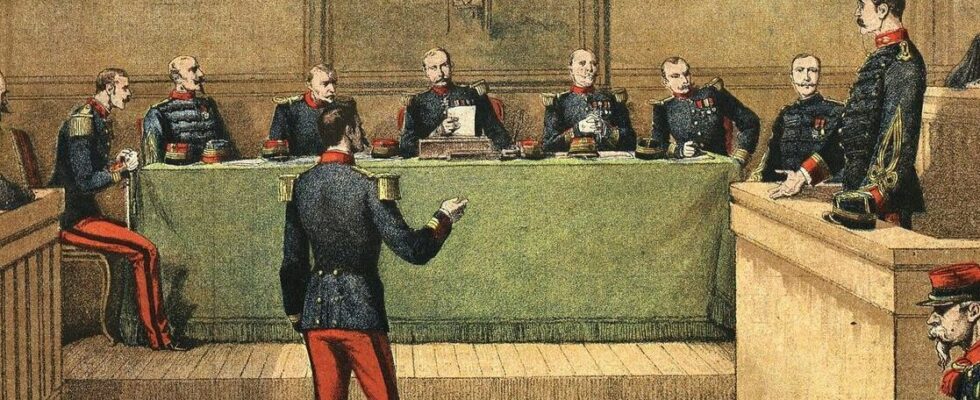

One hundred and thirty years ago, on October 15, 1894, Captain Alfred Dreyfus, a trainee officer at the general staff, was arrested at the Ministry of War, rue Saint-Dominique, in Paris. This thin man, with angular features, this polytechnician, Alsatian Jew, is suspected, on the dubious faith of a famous “bordereau”, of having spied for the benefit of Germany. What followed were three trials, the birth of intellectuals, the exile of Emile Zola, dozens of debates in the Chamber of Deputies, 100,000 articles in the French press, the creation of anti-Semitic leagues, battles of experts, confrontations of arguments – reason of state versus the rule of law; the army against the individual – and millions of clashes at the table. At the end of which, on July 12, 1906, Alfred Dreyfus, twelve years older, was rehabilitated by the Court of Cassation, and reintegrated into the army at the rank of squadron leader.

There is one thing that we sometimes forget with the Dreyfus affair: it lasts a long time. Dividing France at the dawn of the 20th century, it survived three Presidents of the Republic, and around ten Presidencies of the Council. It is not a “controversy” that comes and goes, like an itch, but a long and founding episode, which plays out before the eyes of the world, so fond of the foreign press is it. “A country that is tearing itself apart to save the honor of a small Jewish officer is a country where we must go quickly,” Emmanuel Levinas’ grandfather used to say, rolling his r’s from his native Lithuania.

For many Eastern Jews dreaming of leaving their threatening countries, France became “Zola’s homeland”. His “J’accuse” published by Dawn, titled by Clemenceau, has had a worldwide impact. Previously, the writer had already put together magnificent texts, conveying the multiple dimensions of the emerging affair. In his Letter to youthNovember 14, 1897: “There are anti-Semitic young people, then? So there are new brains, new souls, which this imbecile poison has unbalanced?” In his Letter to Francea few days later : “France, wake up, think of your glory. How is it possible that your liberal bourgeoisie and your emancipated people do not see, in this crisis, what aberration they are being thrown into?” During his trial, finally, in February 1898, the writer urged us to go beyond the particular case, to see the question of principle: “There is no longer a Dreyfus affair, it is now a question of knowing whether France is still the France of human rights, the one which gave freedom to the world and which should give it justice. […] This is an exceptionally serious time, it is about the salvation of the nation.”

The words of Zola, Péguy, Clemenceau, Proust, Blum or Anatole France confront those of Maurras, Barrès, Daudet or Drumont. The old political people are inflamed. On the left, Jean Jaurès – although hardly a philosemite – joined the Dreyfusard camp. In a rally in Lille which opposed him to Jules Guesde in November 1900, the deputy for Carmaux pleaded for the socialists to stop considering the affair as an internal quarrel within the bourgeoisie: “It is the duty of the socialists, when the republican freedom is at stake, when intellectual freedom is at stake, when freedom of conscience is threatened, when the old prejudices which resurrect racial hatred and the atrocious religious quarrels of past centuries seem to be reborn, it is the duty of the proletariat socialist to march with that of the bourgeois fractions which does not want to go back. […] It was Marx himself who wrote these admirably clear words: “We, revolutionary socialists, are with the proletariat against the bourgeoisie and with the bourgeoisie against the squires and the priests.”

“The true birth certificate of the Republic”

The meticulous and painful examination to which the nation was subjected for twelve years took the turn that we make History. “With this fairly simple affair, the Republic went from a political regime of facts – equipped with operating rules – to a regime of principles,” summarizes the historian and philosopher Marcel Gauchet for L’Express. we can say that the Dreyfus affair is the true birth certificate of the Republic.”

One hundred and twenty years after the French Revolution, which made our country the first to grant full civil rights to Jews, the Republic made the case of Alfred Dreyfus its existential question of principle, before the eyes of the world – during the only trial of Rennes in the summer of 1899, the accreditations reveal the presence of 8 German newspapers, 15 British, 9 Italian, 12 American, 4 Spanish, 2 Luxembourgish, 7 Belgian, 4 Austrian, 1 Argentinian, 1 Monegasque, 2 Norwegian, 4 Dutch, 2 Hungarians, 7 Russians, 1 Polish, 2 Swedes, or even 3 Swiss…

Today, at a time when no synagogue, no denominational school, can do without army sentries for its security, the question haunts many French Jews, even in their sleep or their plans for the future. : does France still have something to say to the world on the issue of anti-Semitism?

.