It’s a legal skirmish that Danone and its boss Antoine de Saint-Affrique would have done well without. “Danone, deplasticize yourself!” : this is essentially the message, sent on January 9 by the coalition of NGOs Zero Waste France, Surfrider Foundation Europe and ClientEarth, to the French multinational. An injunction coupled with a summons for non-compliance with the duty of vigilance, since according to the green trio, the juggernaut of yogurt pots and bottled water does not do enough to reduce the proliferation of its polluting packaging to the four corners of the globe. The Rueil-Malmaison group may well say it is “very surprised” by the approach of the NGOs, and recall its status as a pioneer in the management of environmental risks, it does not prevent it. Through this complaint affecting Danone today, and probably tomorrow other large companies, it is the difficulty of this industry to stem the proliferation of plastic waste that is highlighted.

© / M6

>> This week, L’Express is a partner of Capital’s new program “Packaging, waste: the real price of the big mess” to be found on Sunday February 5 at 9:10 p.m. on M6.

The quantity generated for the entire planet, estimated at 353 million tonnes in 2019, could triple by 2060, according to an OECD report. Half will probably end up in landfill and less than 10% in recycling. The world is literally suffocating under the weight of a plastic whose toxicity is well established. The Australian Minderoo Foundation has reviewed more than 5,000 articles by researchers on the harmful consequences of this pollution for man, nature and the economy. “Our action aims to force multinational food and retail companies to publish clear deplasticization strategies. It is not normal that certain groups such as Danone do not mention the issue of plastic at all in their vigilance plan. “, raises Antidia Citores, spokesperson for the Surfriders foundation.

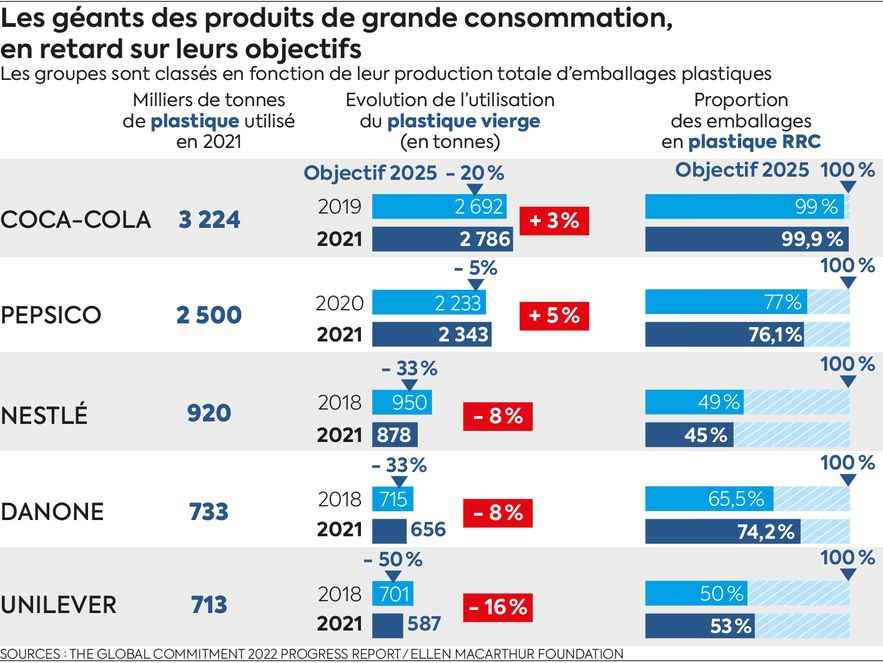

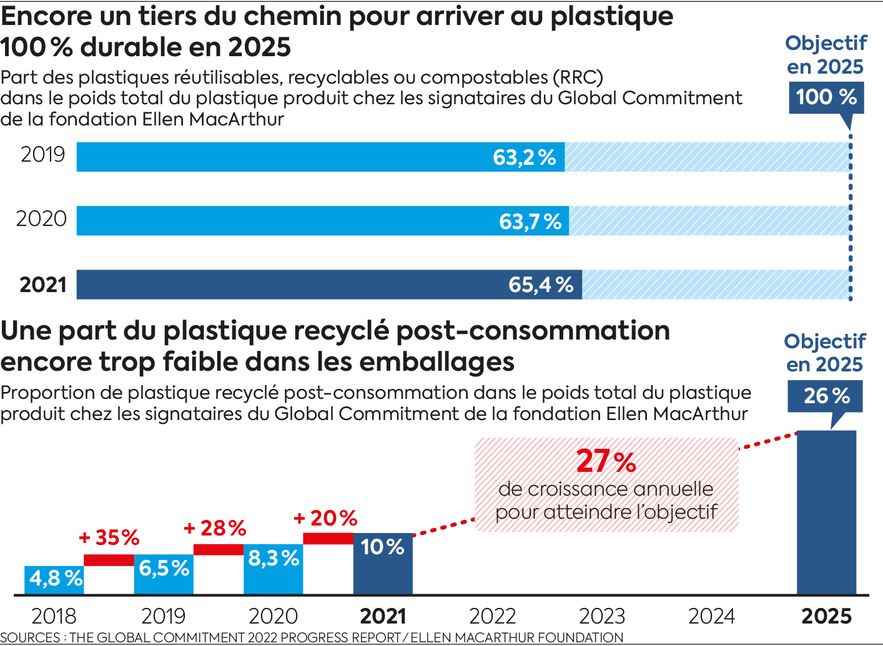

Many of these companies had nevertheless made ambitious promises in 2018 under the Global Commitment led jointly by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation and the United Nations Environment Program. Coca-Cola, Nestlé, PepsiCo, Mondelez, Danone, Unilever, Mars and L’Oréal, to name but a few of the 500 signatories, pledged in particular to drastically reduce the use of virgin plastics by 2025. , and to achieve 100% recyclable, compostable or reusable plastic. But two years from the deadline, the results are very mixed.

© / Art Press

The mirage of 100% durable plastic

Certainly, the MacArthur Foundation recognizes that “the use of recycled containers has doubled in the last three years”. Thus, the share of packaging that complies with the NGO’s specifications continues to increase, reaching 65.4%. However, the goal of 100% sustainable by 2025 seems “unattainable” for most companies. What arouse the ire of environmentalists. “This is proof that promises only bind those who believe in them. These same actors told us, before the law on waste, that it was not worth imposing too many regulatory constraints on them…” attacks Moïra Tourneur, head of advocacy for Zero Waste France.

“What really matters is not so much recycling as the deplasticization trajectory, continues Antidia Citores. Only the latter makes it possible to reduce the number of bottles at the bottom of the ocean.” But from this point of view the account is not there, believe the NGOs. If some companies play the game by developing a clear and visible strategy, this is not the case for all. “Companies have however identified the problem”, assures Eric Mugnier, head of the environmental studies and sustainable development department of Ernst and Young. However, there are still many barriers to change. Tensions over the supply of materials, health and then energy crisis…” “Since 2018, the environment has deteriorated so, inevitably, the commitments made seven or eight years ago are impacted”, explains Marc Madec, director Sustainable Development at Polyvia, the union of polymer processors.

The complexity of supply chains also delays decisions. “Before changing packaging, you have to find the right technical solution that guarantees both packaging while remaining compatible with the recycling channels available. You also have to change raw materials, suppliers, manufacturing methods… he time, there is a lack of technological consensus allowing everyone to invest. Without it, there will not be sufficient economies of scale”, warns Eric Mugnier. Added to these difficulties are those created by the regulations, which often lack precision. “On compostable biosourced packaging, the position of the European Commission and the French State only arrived at the end of 2022. Before, it was a legal vagueness. All the players were wondering if it was necessary to go towards compostable or not. We also dithered to find out what was recyclable. Until recently, there were around thirty different definitions in Europe”, denounces Gilles Dennler, Director of Research at the Industrial Technical Center for Plastics and Composites (CPI).

Regulations that lack harmonization

A difficulty in harmonizing the rules, which leads to very different situations depending on the country. In any case, this is what is suggested by one of the heavyweights in the sector, Nestlé. Questioned by the Express, the Swiss company indicates for example that in France, the rate of its produced plastics which can be recycled reaches 90% in 2022, a target much higher than that noted in the report of the MacArthur foundation. The company also refutes the idea that it will not invest in these new uses and claims to have significantly reduced the weight of its plastic packaging or even the use of virgin plastic. “We are active in 220 projects voluntarily around the world on the collection, treatment-recycling of waste and in 20 pilot projects on reuse, in 12 different countries. On a global level, we actively advocate for a responsible extension of producers, deposit systems or even a legally binding global plastics treaty and the prospect of new harmonized national regulations”, indicates Jodie Roussel Jodie, Global Lead for Packaging and Sustainability of the giant.

Certain efforts, but which fit into a relatively complex chain. The law thus requires companies to control the health and environmental impacts upstream and downstream of their activity. “This creates a mountain of difficulties for them. So very often the large groups prioritize their priorities”, notes Eric Mugnier. In fact, if manufacturers like Nestlé eco-design part of their range, the vast majority of them are not sufficiently present downstream of their value chain even if some are gradually getting started. “Once the packaging is thrown away, the collection-recycling industry takes over, with its own logic and imperatives,” confirms Raphaël Barth, project director at Sia Partners. Upstream in the chain, companies seem even less committed.

During this time, waste accumulates on the ground or in the oceans. “The European directives are ambitious and set the course for reduction. But, as often, the problem is the excessively long implementation times that have been negotiated with the manufacturers. The large groups are not at odds with the directives: they are simply not going fast enough in relation to the climate impact”, analyzes Alexis Normand, the boss of Greenly, a company which helps companies calculate their carbon footprint. The risk, in the long term, is to pay the price, in hard cash.

© / Art Press

For the moment, the fines provided for in the event of non-compliance with the regulations on plastics are very low: barely 1,500 euros per day. Not enough to shake the management of large groups. But the tide could turn, say several NGOs. According to a study by the Minderoo Foundation, the sums to be paid by polymer producers as a result of litigation could exceed 20 billion dollars in the United States alone between 2022 and 2030. After decades of intensive use, plastic don’t bother anyone anymore.